Too Much Sun?

Southern California has some of the best weather in the country, but locals know that near the coast most days in May and June usually start off gloomy — or at least they used to.

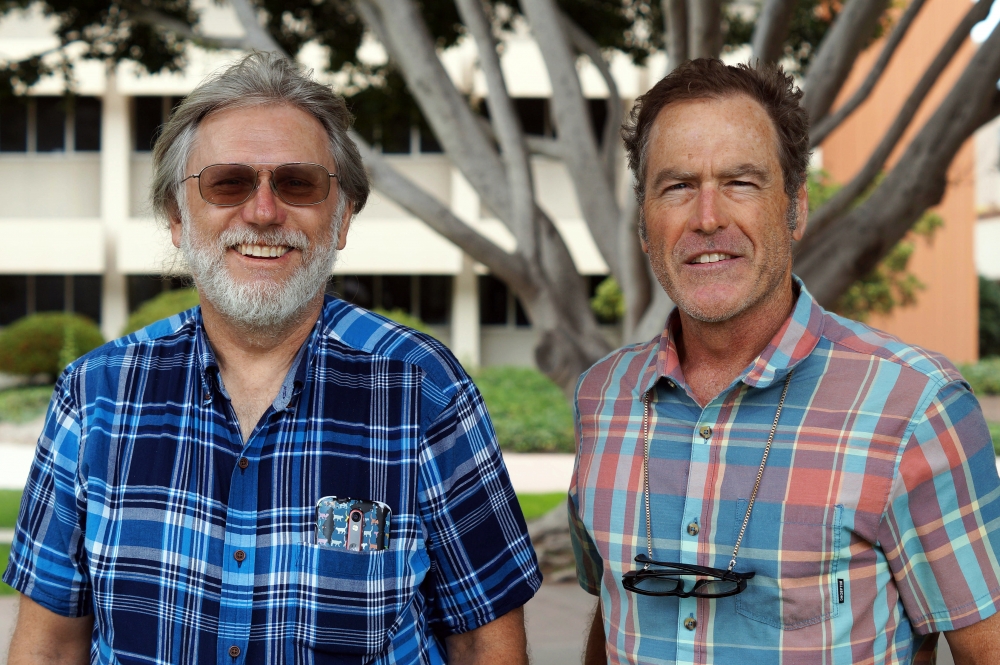

According to a new study, a combination of intensifying urbanization and a warming climate are driving up summer temperatures and driving off once-common low-lying morning clouds in many southern coastal areas of the state. Further, the researchers, including Dar Roberts and Max Moritz from UC Santa Barbara, found that decreasing coastal cloud coverincreases the chance of bigger and more intense wildfires. The results appear in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“The decrease is driven mainly by urban sprawl, which increases near-surface temperatures; however, overall warming climate also contributes,” said co-author Roberts, a professor in UCSB’s Department of Geography. “Increasing heat drives away clouds, which admits more sunlight. That in turn heats the ground further, leading to drier vegetation and higher fire risk.”

In 2015, lead author Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, first documented a decrease in cloud cover around the sprawling metropolises of Los Angeles and San Diego. Urban pavement and infrastructure absorb more solar energy than the countryside does. That heat gets radiated back out into the air, contributing a major portion of the so-called heat-island effect that generally makes cities hotter than the rural areas. At the same time, rising overall temperatures in California due to global warming have boosted the effect. In the new study, the investigators found a 25 to 50 percent decrease in low-lying summer clouds since the 1970s in the greater Los Angeles area.

Normally, stratus clouds form over coastal Southern California during early morning hours within a thin layer of cool, moist ocean air sandwiched between the land and higher air masses that are too dry for cloud formation. The stratus zone’s altitude varies with weather but sits at roughly 1,000 to 3,000 feet. Heat causes clouds to dissipate, and decades of intense urban growth plus global warming have gnawed away at the stratus layer’s base, causing the layer to thin and clouds to burn off earlier in the day or disappear altogether.

“Cloud bases have risen 150 to 300 feet since the 1970s,” Williams explained. “Clouds that used to burn off by noon or 1 o’clock are now gone by 10 or 11, if they form at all.”

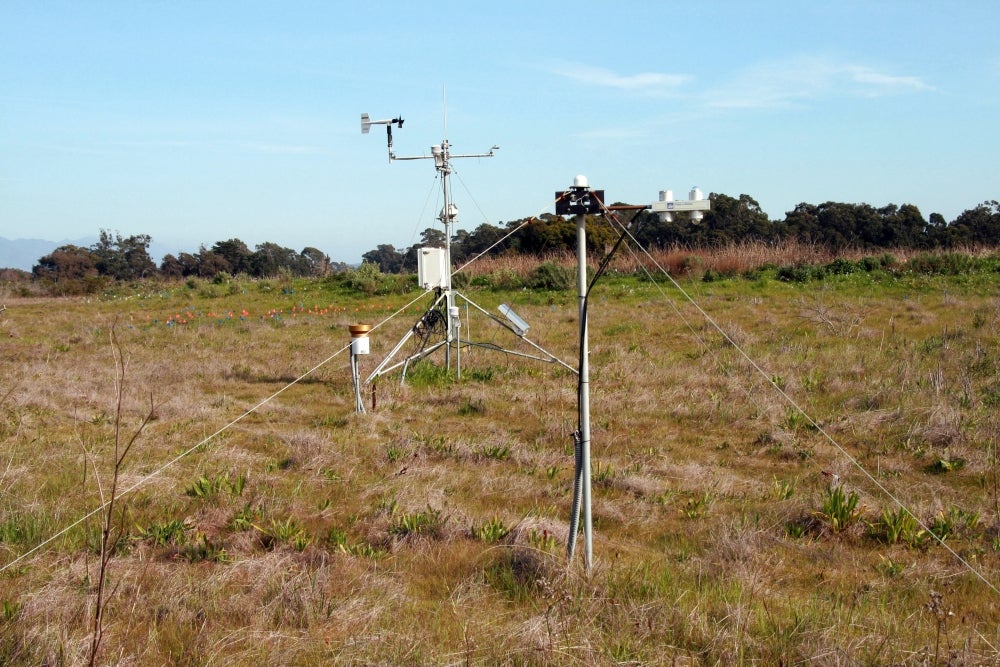

To develop a fine-grained picture of changing cloud cover over the region, the scientists compared hourly cloud observations recorded by small and large Southern California airports since the 1970s with a large database of vegetation moisture levels in the hills outside Los Angeles kept by the U.S. Wildland Fire Assessment System. They found that periods of less cloud cover during the summer correlated with lower vegetation moisture and increased fire danger.

However, the study did not find that total area burned in summer had increased as a result of decreases in cloud shading. In fact, too many other factors are at play, including yearly variations in rainfall; winds and locations where fires start; decreases in burnable area as urban areas have expanded; and the increased effectiveness of firefighting.

“Because fires can already be very difficult to control in these areas, a reduction in cloud cover and its effects on fuel moisture is likely to increase fire activity overall,” said co-author Moritz, a UC Cooperative Extension specialist and adjunct professor in UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “In areas where clouds have decreased, fires could get larger and harder to contain.”

Still, the catastrophic California-wide fires that consumed more than 550,000 acres in fall of 2017 were probably not strongly affected by the reductions in summer cloud cover. Although the study found that vegetation is drier in fall seasons that follow summers with few clouds, the 2017 fires mainly were driven by extreme winds and a late onset of typical fall rains. Conditions vary year to year, but Moritz said he expects fire danger to increase in California as climate change accelerates and people continue to flood the landscape with ignitions.

Other authors of the study are Pierre Gentine of Columbia University and John Abatzoglou of the University of Idaho, Moscow.