Snapshots in Time

George Legrady was just 23 when the James Bay Cree invited him to visit four of their villages to document, through photographs, their way of life in the subarctic of Québec. It was 1973, and the Québec provincial government was pushing a plan that would flood vast areas of Cree land for a hydroelectric project.

Legrady, now a professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Media Arts & Technology Graduate Program, would go on to shoot roughly 3,000 photos over the three months he spent with the Cree, a First Nations people who had been hunter-gatherers on their lands for millennia.

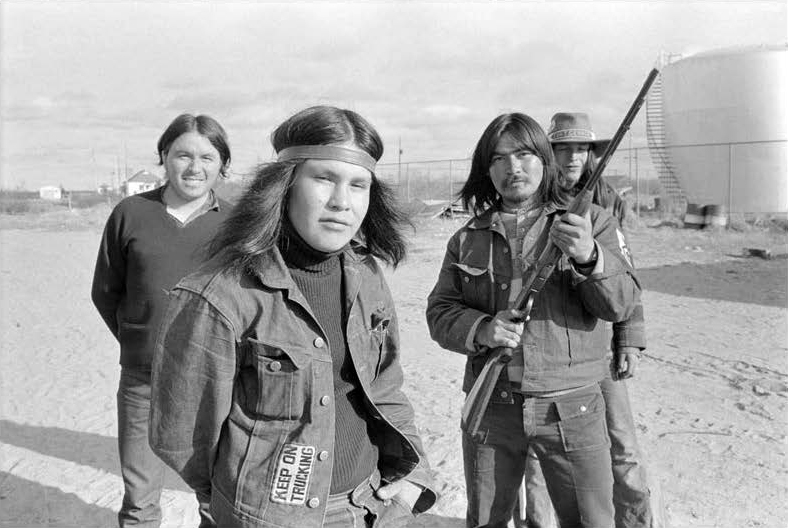

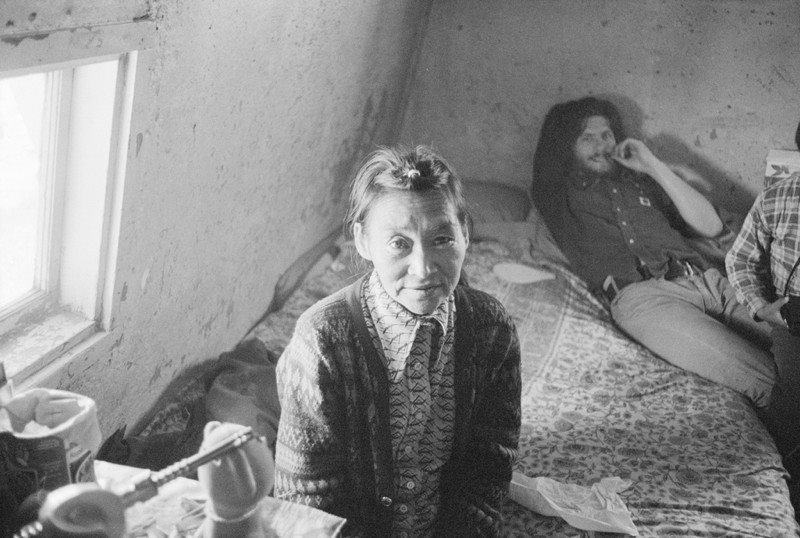

Today, 180 of those images are featured in “The James Bay Cree in 1973,” Legrady’s 65-by-9-foot wall installation on exhibit in the UCSB Library’s Art & Architecture Collection through the spring quarter. The photos are organized in 20 thematic clusters of nine images each showing their way of life in the James Bay Cree villages, from housing to traditional activities, social interactions, weddings, dancing, portraits of elders, young men and women, children, a hunting trip and nature. The exhibition also includes two videos of village scenes recorded during two return trips in 2012 and 2014, edited by Andres Burbano, a Media Arts & Technology alumnus who is today a professor of design and media in Bogota, Colombia.

For Legrady, a digital media artist, the photos are “historical documents.” The Cree find them of critical value, he said, because they represent their ancestors and make them reflect on how their lives have changed.

When the Cree invited him to their James Bay villages, the Québec government was planning to build the James Bay Project, a series of dams for hydroelectric power that would have flooded much of the Cree’s traditional hunting grounds.

Legrady’s photos, which were exhibited in Montreal and Toronto after his visit, gave Canadians an intimate look at the Cree way of life, and of the importance of hunting and fishing. They lived in simple wood homes, but they still hunted, dried fish and largely kept to their traditional ways.

Ultimately, the hydroelectric project flooded a traditional hunting area the size of England, but the tribe gained significant control over 75 percent of its land and self-governance.

“About 5,000 Cree had been hunting on traditional lands in northern Quebec since prehistoric times,” Legrady explained. “The overall territory they had is about the size of Texas or Germany. The Cree had never signed treaties passing the land over to Canada. They began negotiations in 1973 and continue to do so to this day, but they have successfully managed to acquire control of much infrastructure in their communities, receiving royalties, and I believe, they now have ‘nation with a nation’ status.

“The North has yet to settle much of northern Canada,” he continued, “but this may be in the process of changing as climate change opens up the area for mining, shipping and other major industries. These effects will undoubtedly impact the ecologies of the land and the traditional way of life of the First Nations who occupy these lands.”

In 2012, Legrady received a National Science Foundation Arctic Social Science grant to digitize the photographs and present the images back to the Cree. He has digitized and archived about 700 for use by the Cree and ethnographers.

“This photographic project has always been intended to have multiple goals, to reach out to multiple communities and a range of interests that include indigenous history, ethnography, social research, studies in visual communication and the arts,” Legrady said. “As a digital media artist today whose work has focused on interactive installations, data visualization and autonomous camera vision, I consider this James Bay Cree project a crucial first step in my evolution as an artist.”