A Star That Would Not Die

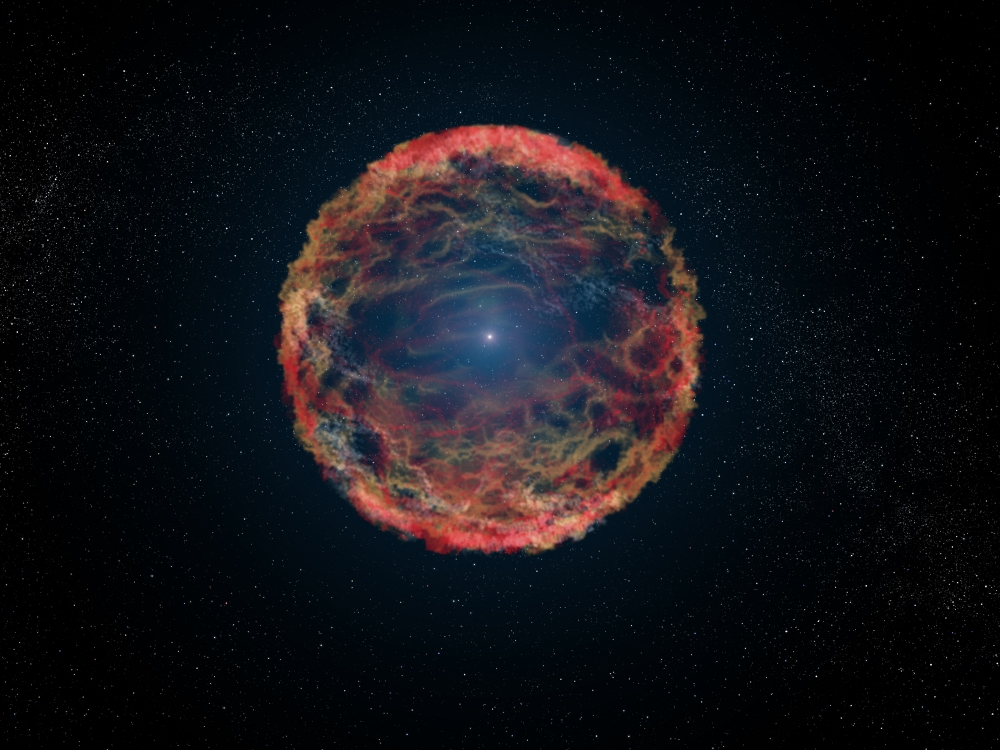

Supernovae, the explosions of stars, have been observed by the thousands. And in all cases, the transient astronomical events signaled the death of those stars.

Now, astrophysicists at UC Santa Barbara and astronomers at Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO) have reported a remarkable exception: a star that exploded multiple times over a period of more than 50 years. Their observations, published in the journal Nature, are challenging existing theories on these cosmic catastrophes.

“This supernova breaks everything we thought we knew about how they work,” said lead author Iair Arcavi, a NASA Einstein postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics and at LCO. “It’s the biggest puzzle I’ve encountered in almost a decade of studying stellar explosions.”

When iPTF14hls was discovered in September 2014 by the Caltech-led Palomar Transient Factory, it looked like an ordinary supernova. But several months later, the scientific team noticed that the supernova, once faded, was growing brighter. It was a phenomenon they had never seen before.

A normal supernova rises to peak brightness and fades over 100 days. Supernova iPTF14hls, on the other hand, grew brighter and dimmer at least five times over three years.

When the scientists examined archival data, they were astonished to find evidence of an explosion in 1954 at the same location. Somehow this star survived that explosion and then exploded again in 2014. In the study, the authors calculated that the exploding star was at least 50 times more massive than the sun and probably much larger.

“Supernova iPTF14hls may be the most massive stellar explosion ever seen,” explained co-author Lars Bildsten, director of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. “For me, the most remarkable aspect of this supernova was its long duration, something we have never seen before. It certainly puzzled all of us as it just continued shining.” As part of this effort, Bildsten worked with UC Berkeley astrophysicist Dan Kasen, exploring many possible explanations.

The earlier explosion in 1954 provided an important clue, suggesting that iPTF14hls could be the first example of a pulsational pair-instability supernova. Theory holds that the cores of massive stars become so hot that energy is converted into matter and antimatter. This causes an explosion that blows off the star’s outer layers and leaves the core intact. Such a process can repeat over decades before the final explosion and subsequent collapse to a black hole.

“These explosions were only expected to be seen in the early universe and should be extinct today,” said co-author Andy Howell, an adjunct faculty member who leads the supernova group at LCO. “This is like finding a dinosaur still alive today. If you found one, you would question whether it truly was a dinosaur.”

The pulsational pair-instability theory may not fully explain all the data obtained for this event because the energy released by the supernova is more than the theory predicts. This means iPTF14hls may be a completely new kind of supernova.

LCO’s supernova group continues to monitor iPTF14hls, which remains bright three years after it was discovered. Their global telescope network is uniquely designed for this type of sustained observation, which has allowed researchers to observe iPTF14hls every few days for several years. Such long-term consistent monitoring is essential for the study of this very unusual event.

“We could not have kept tabs on iPTF14hls for this long and collected data that challenges all existing supernova theories if it weren’t for the global telescope network,” Arcavi said. “I can’t wait to see what we’ll find by continuing to look at the sky in the new ways that such a setup allows.”

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.