Nurturing Warriors

Japan’s history of war, from the late 19th century to the present, shifts dramatically at the conclusion of World War II. After a series of intense conflicts, beginning with the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-95, Japan embraced peace and anti-militarism.

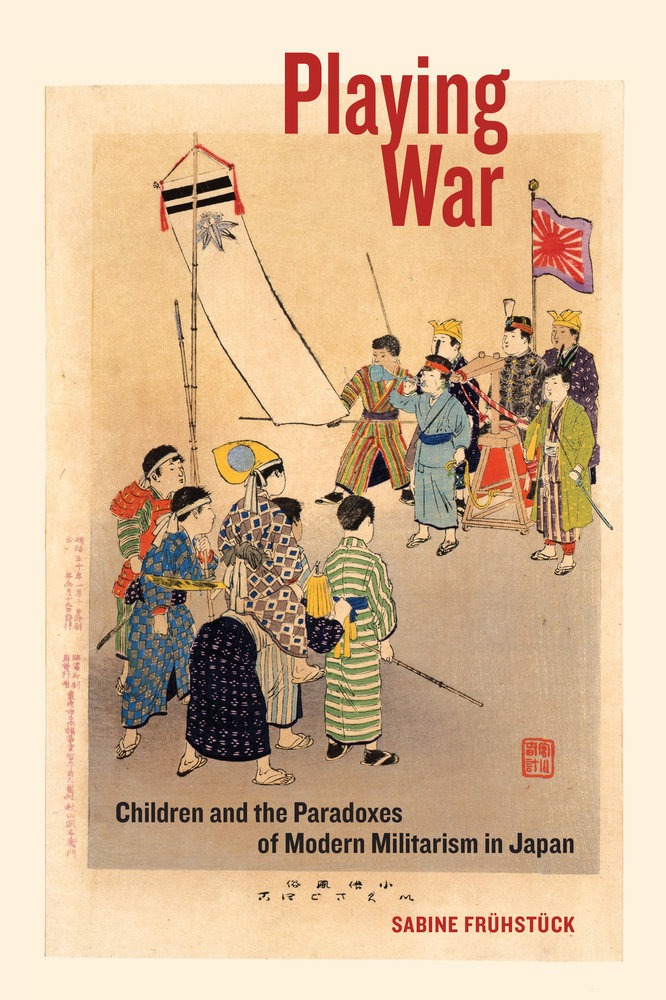

Despite the bifurcation of eras, says a UC Santa Barbara scholar, one aspect of Japanese culture remains unchanged: the use of children to validate war and sentimentalize peace: In “Playing War: Children and the Paradoxes of Modern Militarism in Japan” (University of California Press, 2017) Sabine Frühstück, a professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies, explores the nexus of children and war in the country.

“This is a book about childhood, war and play” Frühstück said, “I wrote it to show how children and childhood have been used as technologies to validate, moralize, humanize and naturalize war and, later, with similar vigor, to sentimentalize peace.”

Frühstück, who is also director of UCSB’s East Asia Center, argues that modern militarism in Japan presents children in dual roles: One as the embodiment of innocence in need of protection, the other as inherently drawn to war. “The modern figure of the child has emerged from a set of contradictory assumptions about children: that children are innately attracted to war, and that they are exceptionally vulnerable to its violence,” she said.

“In examining the intersection of children and childhood and war and the military,” Frühstück explains, “I identify the insidious factors perpetuating this alliance and rethink the very foundations and underlying structures of modern militarism.”

Indeed, the concept of modern militarism — defined as the belief in a dangerous world that demands a military to protect its people — is central to how children underwrite war in Japan, Frühstück said. “In this book, then, the nurturing of such militarism in children and through the use of children, and the resulting militarization of children and childhood, are examined as a modern, multi-modal and enduring effort,” Frühstück said, “I tell the story of how, in Japan and beyond, childhood, war and play have intersected during the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st.”

Although Japan is far from the only country to embrace militarism, Frühstück said the country’s history of nearly chronic warfare from the late 19th century to the end of World War II makes it unique. “Japan is not a typical modern nation state,” she said. “Few other nation states have shared Japan’s trajectory.”

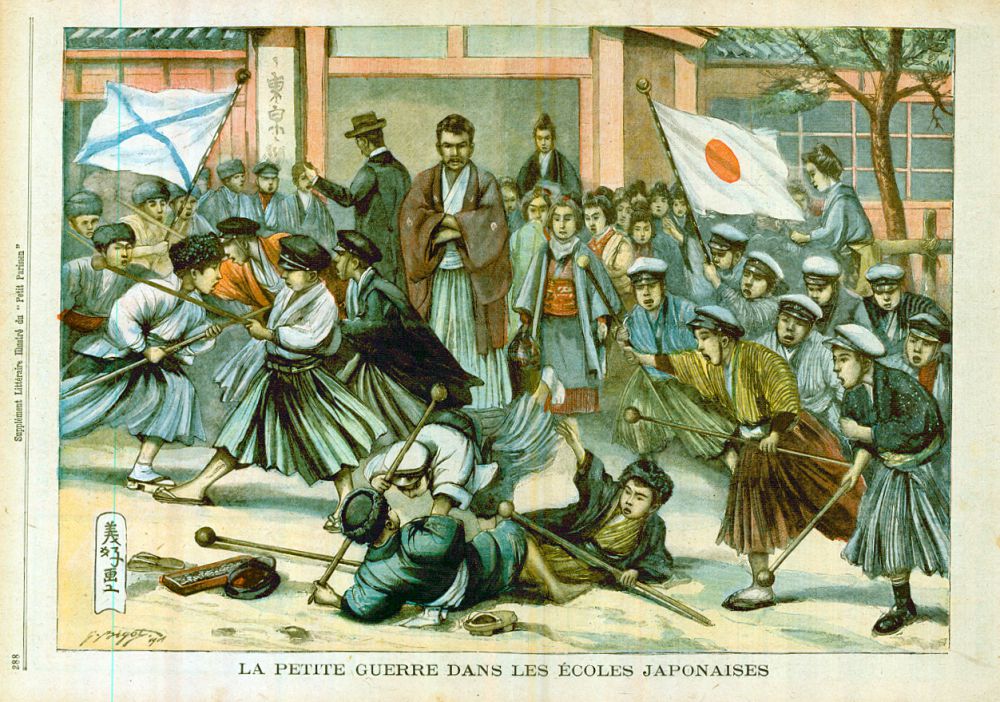

She notes the linkages between children, war and soldiers were formed late in the 19th century and have continued ever since — although they’ve shifted in dramatic ways. Frühstück examines how, early on, children’s games were shaped to be instructive in the art and method of warfare.

The symbolic recruitment of children continues today, Frühstück said. Although Japan’s constitution renounces war and bans traditional military forces, the country maintains the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). But she notes the methods of appropriating children to promote militarism have shifted. With a shrinking population and a younger generation showing little eagerness for war, she said, “the Self-Defense Forces, more than any military establishment elsewhere, have taken a different route, instead variously infantilizing, feminizing and sexualizing service members, potential recruits and sympathizers.”