Thanksgiving Feasts for African Gods

In a different age, women were told that the way to a man’s heart was through his stomach. Elizabeth Pérez, an assistant professor of religious studies at UC Santa Barbara, discovered that in some religious traditions, food is the way to the heart of the gods.

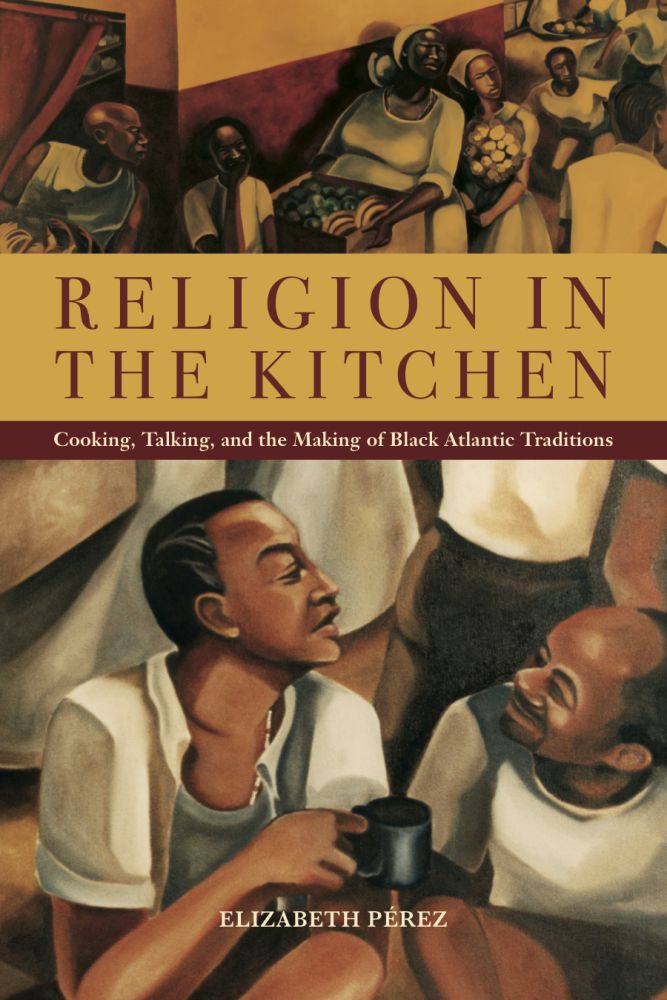

In “Religion in the Kitchen: Cooking, Talking and the Making of Black Atlantic Traditions” (New York University Press, 2016), Pérez argues that in Caribbean and Latin American religions with African roots, the preparation of food is a key ritual in the give-and-take between devotees and the deities they worship.

“Food is a meaningful medium of exchange between gods, ancestors and human beings,” she explained. “And that cooking is itself a ritual process, a form of thanksgiving and praise in many different traditions. The spirits all have favorite dishes and ingredients. But we also have to think about who is doing the cooking, and we need to bring those people to the table when we talk about these traditions.”

Pérez’s fieldwork focused primarily on Lucumí, popularly called Santería, as observed within one black community in Chicago. Her research also touched on other religions with West and Central African origins, such as Haitian Vodou and Brazilian Candomblé. She learned that food preparation is but one element of ritual to be found in the kitchens of shrines and house-temples from Montreal to Buenos Aires. Conversations among the preparers — while they butcher sacrificial meat, for example — play an important role in preserving religious traditions and transmitting them across generations.

These conversations vary. Sometimes they seem like mere gossip, while others, Pérez said, “shape the expectations that less-experienced people have about the ways spirits interact with humans. Senior devotees will say, ‘I didn’t want to be initiated yet the spirits made me do it.’ Or, ‘I didn’t get initiated until I was very ill, and this is the story of how that happened.’ Practitioners aren’t just seasoning food in the kitchen — they are becoming seasoned in the knowledge of how spirits work in the real world.”

Pérez — whose upcoming courses at UCSB will include “The Virgin of Guadalupe: From Tilma to Tattoo” and “LGBT Religious History” — explained that many traditions in the African Diaspora don’t have a centralized authority structure that enforces orthodoxy. “We have to remember that what practitioners are doing doesn’t come down from a pope,” she said. “There’s no pope of Lucumí who is determining what is acceptable. People have to engage actively with the oral traditions that have been handed down to them, and they need to decide in any given moment whether aesthetically something is correct, whether ethically something is correct. In the kitchen these conversations happen where people are deciding, ‘What looks good?’ ‘What looks wrong for the spirits?’ ‘What should be done for them?’ I put those judgments in the hands and in the mouths of women and gay men, where it’s not often been located.”

One of the surprising finds in her research, Pérez said, was the role of gay men in the ceremonial kitchen. “It’s a profoundly female and gay male space,” she noted. “Gay men are not only admitted into the kitchen, in many situations they actually call the shots as to what is going to happen when. For me, that said something about gender, sexuality and racial identity within these traditions that had not been put forward before. It said that these traditions have been able to resist some of the patriarchal norms imposed by the larger societies in which they’ve operated.”

When Pérez began studying Lucumí she focused on aspects such as divination, drumming rituals and major rites of passage. But food captured her attention and changed the course of her research. “I came to realize that food was the hub of the wheel around which the religion has revolved,” she explained. “The more I talked to people about food, the more I talked to them about cooking, the more I felt I had hit on something that was common to other African-derived religions throughout the Americas.

“I’m hoping people will come away with a better appreciation for the way ‘idle’ conversation can shape the way a religion perpetuates itself in the modern world,” she continued. “There’s a joke among professors that if you really want folks at a special lecture or seminar, you bring food. It’s the same thing for the gods; if you want the spirits in your life, you’ve got to bring food.”