A Violent Enigma

In the early dawn on Arizona’s Antelope Mesa, a large force of raiders annihilated the people of an ancient Hopi village. The carefully planned attack in the fall of 1700 was so violent that the village became a haunted scar on the landscape.

Raids weren’t all that unusual in the Southwest; Apaches, Navajos, Utes, Comanches and others had fought one another for generations. What made the destruction of Awat’ovi unique was that the attackers were Hopi from nearby villages and clans.

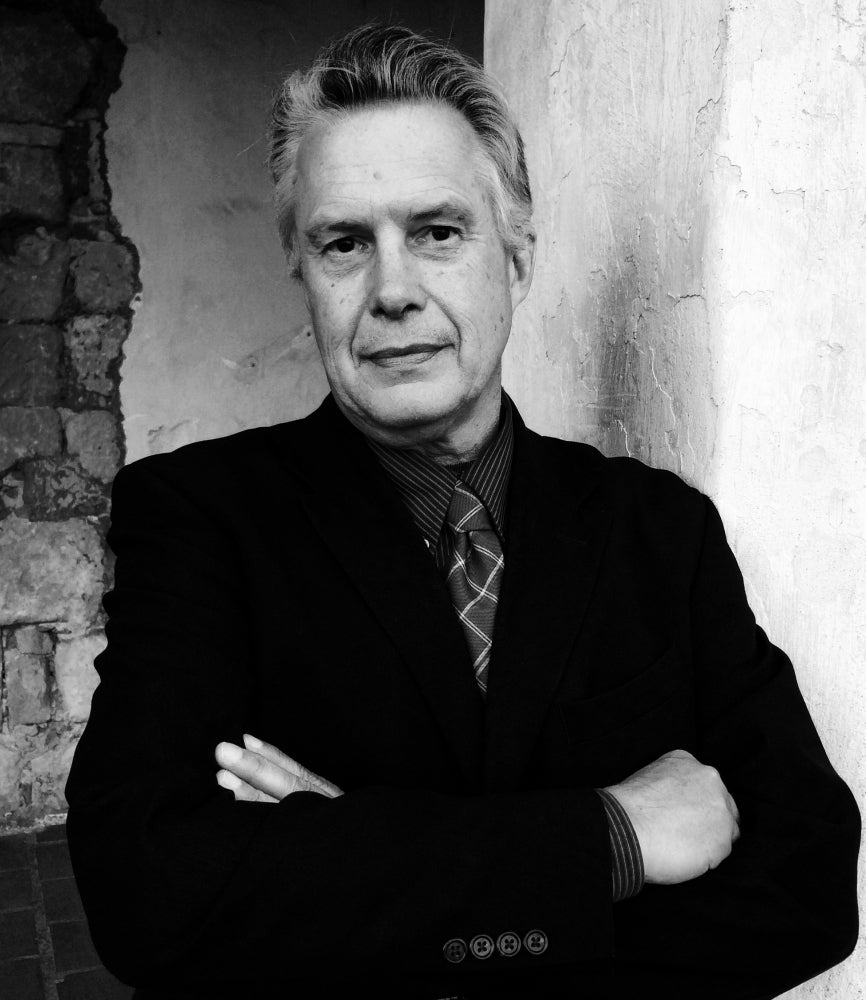

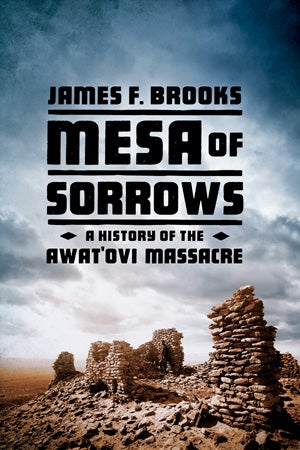

James F. Brooks, a professor of history and of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara, examines the event anew in “Mesa of Sorrows: A History of the Awat’ovi Massacre” (W.W. Norton & Co., 2015). The book traces not just the mechanics of the event, but its impact on the culture and humanity of the killers and their victims, from the day of the deed through a century of archaeological excavation to the present. And it seeks to answer a broader question: How does such violence happen?

“A question that always bothered me was, ‘How do we understand intracultural violence?’ ” Brooks said. “It’s easy enough to see why Apaches and Spaniards hated each other and preyed on each other and all that. But what happens when communities just implode?”

Although the destruction of Awat’ovi is no secret in the Southwest, it was largely unexamined. Brooks, who wrote the landmark “Captives & Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands” (The University of North Carolina Press, 2002) thought the time was right to take a look at the massacre. He found that what happened in the village was fairly straightforward, but the reasons for it proved to be far more nuanced and veiled by the particulars of culture, history and religion.

“As with so much in life, you think you kind of know what you’re doing, and you find out you don’t,” Brooks explained. “It all became a matter of the elevation at which you’re looking at things. At 30,000 feet everything looks one way, but at 5,000 it looks very different. And this became, then, very much a 5,000-foot, maybe a 500-foot, book.”

What he found at that altitude was a history rich with villages and clans — Hopi, yet distinct from one another. Each had a role in the massacre — as perpetrators and victims — and each had its own story and interpretation of the circumstances surrounding an orgy of violence that still stings today.

“How can perfectly decent people do perfectly terrible things?” Brooks asked. “And then once you’ve acknowledged that, how do you move on? By the time I had done all the reading and thinking and research it felt to me like there was at least one way to tell this story that leads to a sense of understanding and forgiveness for perpetrators and victims alike. That’s why I was very careful to stay with this as a history, not the history. A history at once very particular to a place and time, yet perhaps universal.”

Hopi historian Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert of the University of Illinois agrees, saying that the book “recalls the history and legacy of the Awat’ovi massacre by brilliantly connecting the past to the Hopi present. It is a story of violence, destruction and annihilation … but it is also a story that is deeply rooted in the human experience.”

The deeper meaning of Awat’ovi might best be seen in the Hopi themselves, Brooks said. The ruins of the village are largely untouched, a shattered town of collective trauma. It lives in the massacre’s descendants — the killers, the dead and the survivors. Awat’ovi is a reminder of who they are and who they don’t want to be.

“I think these kinds of incidents live in all nations and peoples,” Brooks said. “One of the shocking things about this story is, how can it be? ‘Hopi’ means ‘the peaceful people.’ They’re the archetypical, self-sublimating communitarian people. They dance for the world, not just for their katsinam. And yet this startling case of internecine violence occurs among Hopis. My point is to suggest that sometimes you keep painful pasts alive in order to help guide your future.”

Brooks will sign copies of “Mesa of Sorrows” at Chaucer’s Bookstore in Santa Barbara Tuesday, Feb. 23, at 7 p.m.