Fact and Fiction

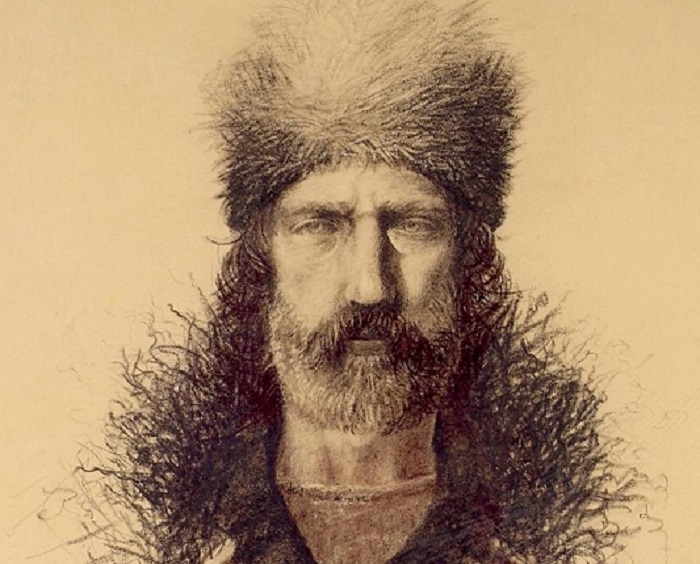

In “The Revenant,” Oscar-bound actor Leonard DiCaprio’s Hugh Glass, clinging to life after a brutal mauling at the claws of an angry grizzly, watches helplessly as a fellow fur trapper kills his son. It’s a gut-wrenching, gripping bit of film.

As a history lesson, though? Three words: grain of salt.

Glass did exist — he’s a frontier legend — and a bear did attack him. But the real Hugh Glass didn’t have children. According to historical records, his survival was driven by a determination to avenge the theft of his gun, not the death of a son. It’s a fact apropos of the time — one’s gun was everything — but of Hollywood? Not so much.

Director Alejandro G. Iñárritu never promised historical accuracy — he clearly stated otherwise — but that didn’t stop critics from the armchair to the arthouse, and history buffs everywhere, from debating the details and breaking down the differences between the film and its real-life inspiration.

And so it goes with the slew of other recent major movies based on true events — “The Big Short,” “Spotlight,” “Suffragette,” “Trumbo,” to cite a few. And so it has gone, say scholars of film and history alike, every year since the very inception of what is now known as the movie industry.

“The question of creative license versus historical accuracy dates all the way back to the silent era,” said Joshua Moss, a visiting assistant professor of film and media studies at UC Santa Barbara. “The Lumiere Brothers’ first one-reelers in the 1890s were called ‘actualities,’ implying an inherent truth to the captured image. Similar debates usually accompany any film or television show that recreates famous historical events. The criticism focuses on the inherent tension between historical events and the need for material that will satisfy audience demands established by narrative screen traditions. The need for three-act structures, happy endings and a clear protagonist’s journey often reduce complex historical events to fodder for mainstream entertainment.

“The solution, as films such as ‘The Revenant,’ ‘Steve Jobs’ and ‘Trumbo’ show, is for these films to focus entirely on the protagonist journey, allowing major historical events to recede into the background,” Moss continued. “This de-emphasizes any claim of historical accuracy. It’s one semi-solution to an intractable problem when fictional screen media tries to recreate famous events. This tension will likely grow even more as ‘history’ is recorded by better and better technology.”

Filmmakers who aim to be accurate, or at least to do right by history in their retelling, tend to end up in the crosshairs, according to Moss. For example, he cited the backlash against 1977 television miniseries “Roots,” a “well-intended corrective that was criticized for taking the generational tragedy of slavery and turning it into primetime soap opera melodrama.”

Consider “Gone With the Wind.” The iconic film paints a romantic (and sympathetic) picture of the Old South, but at what cost? Taken as even a remotely close reflection of that time, say historians, such a movie can do real damage to our understanding of the past.

“In that sense, a film like that is really sort of painful,” said Sarah Case, a lecturer in UCSB’s Department of History and managing editor of the UCSB-based scholarly journal The Public Historian. “To my mind, movies that attempt to say something historically rather than just use history as background are worth our attention. But things that are not engaged in history in a serious way can stay in entertainment.”

“It’s a complex thing,” Case continued. “What is the line between history and entertainment? When do we see something as pure entertainment based on historical events, or when do we see it as conveying a sense of the historical past, even though it’s not completely accurate? Because they’re never accurate in a perfect way, and maybe that’s OK. Maybe the connection is worth it — the way a film can connect viewers to historical material and to history.”

Film scholars widely agree with that assessment. The issue is so perennial, says Cynthia Felando, a film and media studies lecturer at UCSB, that it is largely now assumed there will be at least some minor meddling, whether with premise or props, dates or small details.

“There are so many layers of possibility if one wants to target something as untruthful or inaccurate,” noted Felando, who said the crux of the problem lies in the unavoidable condensing of facts that comes with adapting a story for film. “Take ‘All the President’s Men.’ If we saw every step those reporters took in their investigation, with no consolidation of characters and events, we’d still be watching that film today.

“I think people in general, unless they have a vested interest in the story that’s being depicted, generally accept that liberties are going to be taken,” Felando added. “I read those challenges to authenticity as ways to engage people with the subject matter and as an opportunity to use popular film as a way to encourage greater interest in and more discussion of these topics. Who can ever know the 100-percent facts anyway?”

And therein lies the big takeaway. In the matter of film vs. history, perhaps that malleable notion known as truth is the winner.

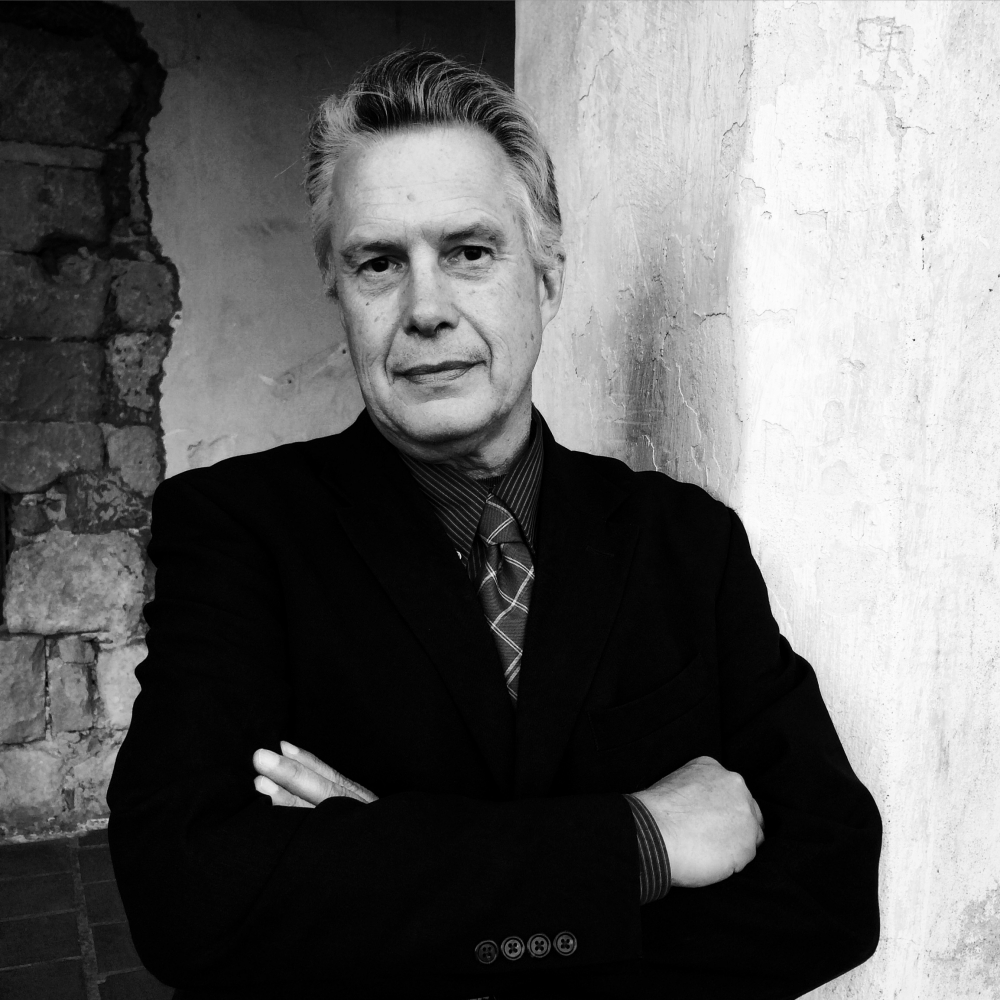

“We had the same kinds of conversations around ‘12 Years a Slave’ when that movie came out — everybody went running to the historians,” said James Brooks, a UCSB professor of history and of anthropology, and editor of The Public Historian. “Well, did it move you? Did it make you think about slavery? Did it make you abhor slavery? Did it make you see the horrible power dynamics of women-on-women violence inside those households? I don’t care if it’s true or not as long as it brings you into those feelings. I’m sure many people, after seeing the film, ran out and bought the book. And thank goodness. That’s wonderful. They got a first-person, real-time account of life in slavery.

“The whole nature of history and why it’s fun to be a historian is that it’s fragmentary — it leaves you space to try to connect the vacancies and the absences,” Brooks added. “How different is that from the novelist or the poet or the painter who is trying to find a way to create some truth in human experience?”