Revolutionizing the Study of Security Regimes and Global Change

UC Santa Barbara’s Paul Amar is turning the world of sociopolitical academia upside down, and he’s doing it one book at a time.

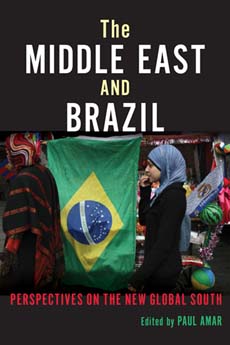

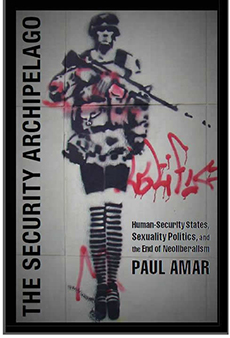

The associate professor of global studies is the editor of “The Middle East and Brazil: Perspectives on the New Global South” (Indiana University Press, 2014) and the author of “The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexual Politics and the End of Neoliberalism” (Duke University Press, 2013), which recently received the American Political Science Association’s Charles Taylor Best Book of the Year Award for 2014. The award honors the “best book in political science that employs or develops interpretive methodologies and methods.”

Although they tackle disparate subjects, “The Middle East and Brazil” and “The Security Archipelago” upend conventional thinking about geopolitics, state security, sexuality and social movements. And that’s perfectly fine with Amar.

For him, academic innovation is in the DNA of UCSB’s Global & International Studies Program. In fact, the university is launching a Ph.D. program in September, with Amar serving as director. It is the first of its kind at a major research university. Rather than viewing world events as the stereotypical product of machinations originating in the global north (principally the U.S. and Europe), Amar has focused on regional factors and actors within Latin America and the Middle East in particular that have provided dynamics of change and have created space for the emergence of new regimes of power as well as tactics of resistance.

“It’s not just looking at either the legacies of colonialism from the top, or to seeing change from below in terms of resistance and difference,” Amar said. “Geographies of domination, security and social change flow in contradictory directions in today’s globalized orders. This is part of the philosophy of the Global Studies program, not to follow the traditional routes and maps.”

Take “The Security Archipelago” for example. It is the product of 10 years of research that focuses on militarization of society and the articulation of seemingly “humanitarian” forms of governance in Brazil and Egypt. It’s a sweeping, multidisciplinary examination of how two former military dictatorships came to embrace what Amar labels “the human-security state” — protecting human rights among sexual and racial minorities while promoting cultural rescue and heritage preservation. Amar also analyzes how these seemingly protective, progressive projects then morphed it into vehicles for intensifying and extending, rather than challenging, repressive authoritarianism.

Amar found that the human-security state developed independently in two countries with few apparent geopolitical connections. “Starting in the late 1990s, both the police forces and the militaries started intensively talking about cultural rescue and heritage preservation — and talking to each other across global-south regional divides,” he said.

“These once-progressive campaigns to protect the cultural sovereignty of indigenous peoples or cultures of threatened minorities got hijacked, turned into mechanisms for arresting those deemed ‘perverse’ or to cleanse places of the unrespectable or vulgar or who constituted a sexual threat to national reputation.”

What surprised Amar, and what remains one of the book’s key insights, is that the human-security state spread through a virtual archipelago of laboratory sites that skirted the capitals of northern powers. “What I call the ‘security archipelago’ produces spaces for pioneering new forms global governance that blur repressive and progressive projects and launch new forms of globally circulating identity,” he said. “Here in the archipelago we can glimpse how the socio-political geography of the planet is changing. This book provides a vision distinct from those who see global power as always trickling down from London or Washington or formal centers of finance or see history as propelled by a monolithic story of colonial legacies seen as not disrupted by global-south struggles on the ground.”

In another recently released volume, “The Middle East and Brazil,” Amar and an international group of scholars trace the centuries-old historical, cultural political connections between the two regions and the alliance they forged early in this century. Termed ASPA — the Summit of Arab and South American States — the alliance is a determined break from the influence of Eurocentric geopolitics.

Amar said the spark of that new alliance came from Brazil’s then-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Known universally as Lula, in 2003 he became the first Brazilian head of state in 100 years state to travel to the Middle East. And when he did, he arrived with a surprise.

“Lula wanted Brazil to join the Arab League — kind of a crazy idea. This is Lula’s style,” Amar explained. “He said, ‘We have 8 million Arabs in Brazil, more Arabs than there are in Lebanon or Palestine or Tunisia, so why can’t we join the Arab League?’ So they did, actually. Well, Brazil was accepted as an Arab League member with observer status.”

A large Arab population wasn’t the only reason Lula reached out to the Middle East. The United States that year had invaded Iraq amid worldwide protests, and Brazilians were overwhelmingly opposed to the war. Lula and others saw it as an opportunity to revive a new form of Third World solidarity, with Brazil spearheading an alliance of global south countries.

“Lula wanted to champion this alternative view of dealing with the Middle East as a cultural partner, as a social partner, as a counter-hegemonic region that that shares a history with Latin America, instead of as just a theater for war,” Amar said.

Also in 2003, Amar, with Brazilian anthropologist Paulo Pinto, co-founded the Center for Middle East Studies at Federal University Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro. The group of scholars held its first conference while Lula was in the Middle East. Many of the contributors to “Brazil and the Middle East” attended that conference, which laid the groundwork for a new way to do transnational studies that looked beyond the fulcrum of war and beyond the top-down, north-centric approach.

“We wanted to demilitarize this approach to looking at connections between the Americas and the Middle East, but still keep security and military issues in our optic,” Amar explained. “So it was founded on this revival of transnational cultural and social and historical approach of looking at the two regions. It wasn’t just an academic project, it was part of a moment trying to imagine how the emergent world regions could relate to each other beyond the frameworks established either by Bush’s wars or through international financial systems like the IMF.”

Amar added that with this global conversation between Latin American, Arab, African and U.S. scholars, he and his colleagues began to see things in new ways and to produce exciting concepts and methods for research that may expand possibilities for understanding, policymaking and cooperation in the future.