Coexist or Perish

Many fire scientists would like Smokey Bear to hang up his prevention motto in favor of tools like thinning and prescribed burns, which can manage the severity of wildfires while allowing them to play their natural role in certain ecosystems.

A new international research review, led by Max Moritz, an associate at UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), says the debate over fuel-reduction techniques is only a small part of a much larger fire problem that makes society increasingly vulnerable to catastrophic losses unless it changes its fundamental approach from fighting fire to coexisting with fire as a natural process. The findings appear today in the journal Nature.

“We don’t try to ‘fight’ earthquakes: we anticipate them in the way we plan communities, build buildings and prepare for emergencies,” said lead author Moritz, also a cooperative extension specialist in fire at UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources. “We don’t think that way about fire, but our review indicates that we should. Human losses will only be mitigated when land-use planning takes fire hazards into account in the same manner as other natural hazards such as floods, hurricanes and earthquakes.”

The review examines research findings from three continents and from both the natural and social sciences. The authors conclude that government-sponsored firefighting and land-use policies actually incentivize development on inherently hazardous landscapes, amplifying human losses over time.

The analysis examines different kinds of natural fires, what drives them in various ecosystems, the ways public response to fire can differ, and the critical interface zones between built developed communities and natural landscapes. The authors found infinite variations of how these factors can come together.

“It quickly became clear that generic one-size-fits-all solutions to wildfire problems do not exist,” Moritz said. “Fuel reduction may be a useful strategy for specific places like California’s dry conifer forests, but when we zoomed out and looked at fire-prone regions throughout the western United States, Australia and the Mediterranean basin, we realized that over vast parts of the world, a much more nuanced strategy of planning for coexistence with fire is needed.”

The authors recommend prioritizing location-specific approaches to improve development and safety in fire-prone areas, including adopting land-use regulations and zoning guidelines such as restricting development in the most fire-prone areas, and building codes that require fire-resistant construction to match local hazard levels and encourage retrofits to existing ignition-prone homes.

The paper also suggests implementing locally appropriate vegetation management strategies around structures and neighborhoods; evaluating evacuation planning and warning systems, including understanding situations in which mandatory evacuations are or are not effective; and developing household and community plans for how to survive stay-and-defend situations as well as better maps of fire hazards, ecosystem services and climate change effects to assess trade-offs between development and hazard.

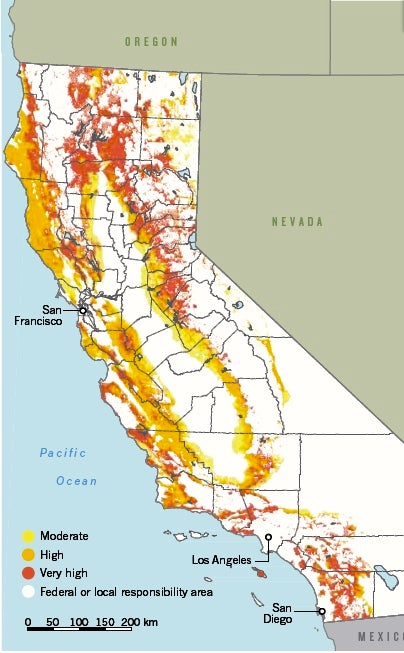

As an example of positive steps, the report cites new fire danger mapping efforts, including an existing fire hazard severity zone map that guides building codes in California. Produced by the state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, the current map does not explicitly incorporate locally varying wind patterns, which influence the worst fire-related losses of homes and lives, but future iterations will include these data.

“Wildfires are a natural part of many ecosystems and can have a positive long-term influence on the landscape, despite people labeling them as disasters,” said co-author Dennis Odion, an associate project scientist at UCSB’s Earth Research Institute. “They can often stimulate vegetation regeneration, promote a diversity of vegetation types as the intensity of fires varies, provide habitat for many species and sustain other ecosystem services, such as nutrient cycling. However, where exotic species are invading, fires may be harmful, so there is a need for site-specific analyses.”

Odion is the lead author of a PLOS ONE paper published earlier this year that examined the frequency, size, seasonality, impacts and other characteristics of naturally occurring fires in Ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of western North America. The findings show that prior to settlement and fire exclusion — the elimination of all types of wildland fire from a specified area — these forests historically exhibited much greater structural and successional diversity as a result of fires burning with complex patterns of intensity.

“This is often the byproduct of weather patterns as we see in modern wildfires,” Odion said. “This can limit the effectiveness of fuel treatments and is one reason why the kind of coexistence strategies described in this just-published paper are needed.”

“A different view of wildfire is urgently needed,” Moritz concluded. “We must accept wildfire as a crucial and inevitable natural process on many landscapes. … There is no alternative. The path we are on will lead to a deepening of our fire-related problems worldwide and will only become worse as the climate changes.”