Reimagining Climate Justice

The climate crisis — and it is a real crisis — is probably the greatest challenge that humanity has ever faced, and the outcome will depend on what we who are alive today do in the next few decades, starting now. So said UC Santa Barbara sociology professor John Foran in the opening ceremony of the Climate Justice Conference held at UC Santa Barbara on Saturday, May 10, in Corwin Pavilion.

The multimedia conference was the culmination of a yearlong effort to document the climate justice movement, which advocates for a more democratically inclusive world. The Climate Justice Project is an offshoot of International Institute of Climate Action and Theory (IICAT), which Foran co-founded with alumnus Richard Widick, a visiting scholar at the campus’s Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies. Foran is the 2013-14 UCSB Sustainability Champion, and the conference was also his capstone effort in that capacity.

“I consider today a new beginning as much as an ending,” Foran said. He and most of the participating climate justice experts hold that there is a possibility for change and that no matter how remote, it is imperative that we try to make that change happen. Foran and Widick will be attending the December Conference of the Parties (COP 20) meeting in Lima, Peru, to bring their message to United Nations climate negotiations.

“I think the horrific and universal catastrophe imminent in climate change demands new forms of life and productivity and collaboration,” said Widick. “Climate change and global warming are here; they’re here now. Those are the scientific facts.”

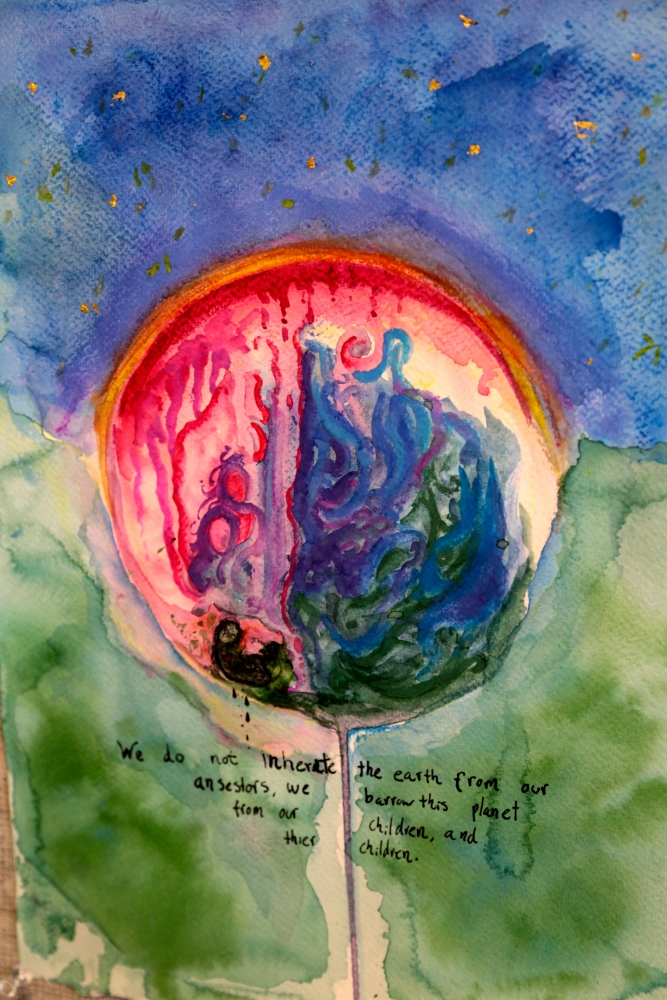

Part workshop, part art exhibition, the conference featured a variety of artwork such as “Capitalism,” a skull made out of recycled plastic pieces mounted on salvaged wood painted with acrylic. According to the artist, Jami Joelle Nielsen, the piece addresses “the incompatibility of capitalism and climate justice and seeks to encourage knowledge and action on issues of consumption.” An installation by artist/philosopher Carter Brooks featured blocks of ice melting over metal into aluminum receptacles. The melting freed articles such as keys and railroad spikes that were embedded in the ice.

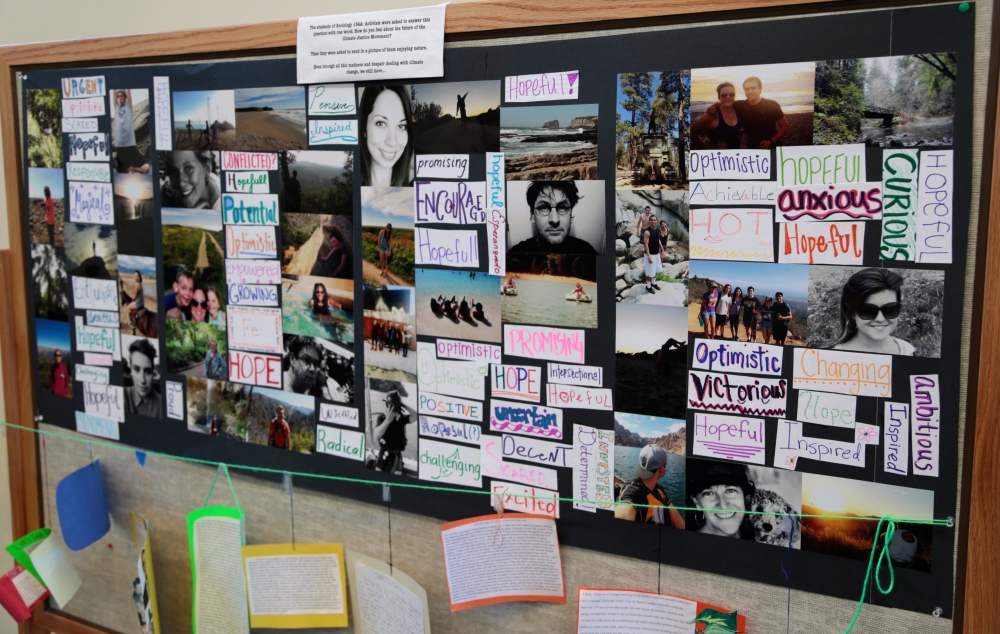

Elsewhere, the conference combined artistic expression with social consciousness in new and unexpected ways: a workshop that explored art and music as tools for social change; an exhibition of elementary and high school art about climate change; and a creative space where attendees could express their ideas about climate justice, climate change and the future using video, making art or designing patches.

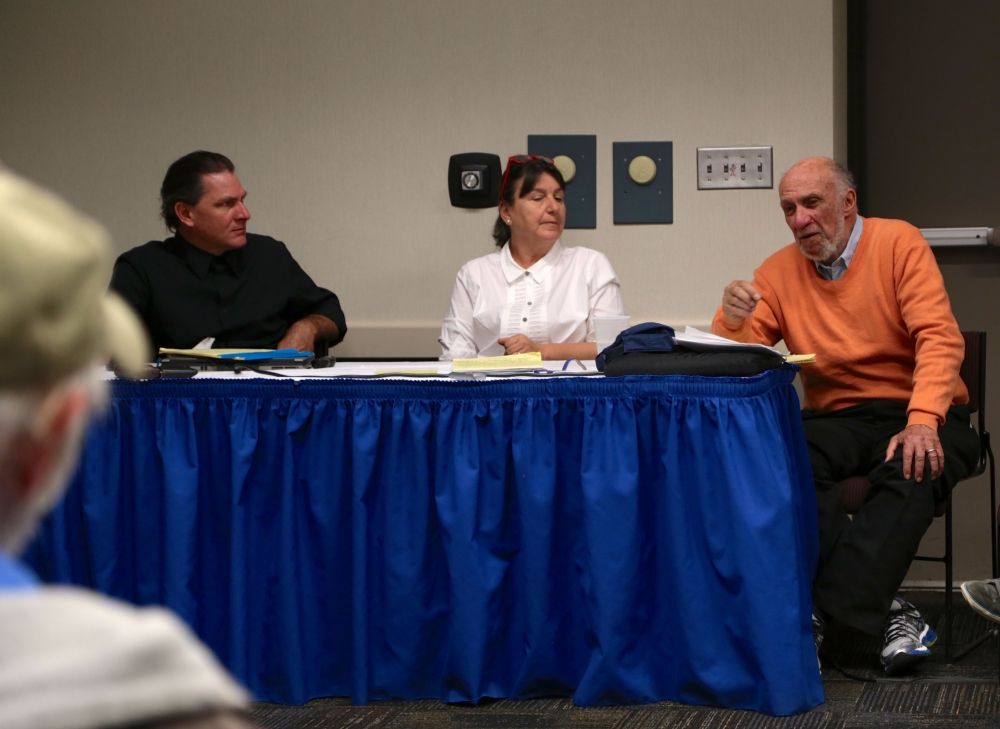

Other breakout sessions included workshops that taught creative confrontation in action or discussed how to fight for survival and justice while maintaining a spirit of joy. A panel discussion led by Widick along with Foran and Hilal Elver and Richard Falk, fellows at the Orfalea Center, laid bare the legal and political nature of the U.N. climate summit process.

“Climate change will increasingly become in the years and decades to follow the central dilemma through which humanity as a whole and individuals and groups and nations everywhere will confront their most pressing existential questions,” Widick said. “Why am I here? What am I worth? What can I do? What is possible? What’s valuable? What’s worth struggling for? And finally, very simply, what is it that I want?”

The answers to those questions are not the same for everyone. “I’m here because I agree in the principles and goals of this movement and organization but I strongly disagree that climate change is an appropriate motivation,” said conference attendee Thomas Flood, a former electronics engineer and computer software engineer who has spent the last 15 years as a nurse. “The science of climate change is not really proven and there are many other problems such as nuclear war or biological warfare that could also be big problems.”

A presentation led by environmental science professor David Cleveland addressed the hypothesis that diet change is a key to the implementation of both climate justice and food justice. “The diets of the most powerful people use many more resources than the diets of least powerful people,” Cleveland said. “The agrifood system is responsible for at least 30 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Diet change is a way we can affect climate justice by reducing greenhouse gas emissions of the most wealthy people and also free up resources for food for the least powerful people.”

The conference wrapped up with the World Café, where participants gathered in small groups to discuss the highlights of the day. “This gathering felt like what we had set out to do from the beginning,” Foran concluded, “to re-imagine what is possible and hopeful in the biggest fight of our lives — bringing about climate justice and tapping into the creativity that all people, but especially young people, can bring to that project.”