Newly graduated from college nearly 20 years ago, Kate McDonald and a group of friends spent 31 days walking the centuries-old Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route through Spain. Several weeks in, on a particularly busy and dangerous stretch along a crowded urban roadway, they flagged a cab. For the next 20 minutes, they were safely transported a distance that would have taken several arduous hours on foot.

Reflecting on that easy cab ride through a tough stretch, McDonald remembers feeling a mix of relief and astonishment. Years later, she would begin to draw on that experience, combining it with her enchantment and scholarship of Japanese culture to explore the history of transportation on the East Asian island country.

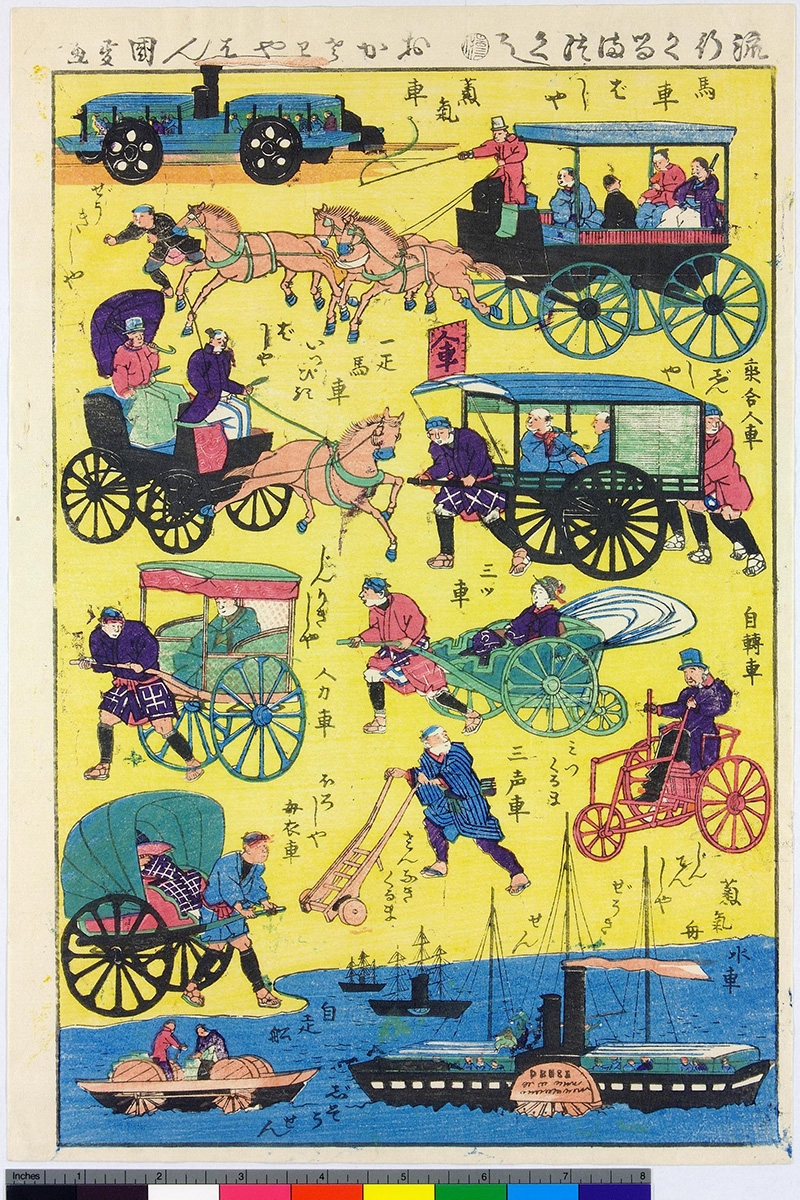

Her forthcoming book on the topic, "The Rickshaw and the Railroad: Human-Powered Transport in the Age of the Machine,” takes on a “retelling of the history of transport as a history of people rather than devices,” said McDonald, an associate professor of history at UC Santa Barbara. “Transport workers are part of society as a whole, an important part. And if we are going to consider the benefits of new transport technologies, we have to consider the workers as well.”

With a recent grant award from the National Endowment for the Humanities, McDonald plans to travel to Japan over the next year to conclude her research and finish writing the manuscript, she said.

Japan is a country and culture near and dear to her heart, she added, dating back to a trip to the Kansai region with her high school orchestra. A year later, as a freshman at Georgetown University, she studied the language, and in her third year attended Nanzan University during a yearlong study abroad program; she graduated with a B.A. summa cum laude in Japanese language and culture. In grad school at UC San Diego, McDonald studied modern Japanese history. She joined UC Santa Barbara’s Department of History in 2011; she is also the director of the university’s East Asia Center.

With the news of the NEH grant, The Current caught up with McDonald for details on the project.

The Current: Go into a bit more detail about how your book project connects to that a-ha moment in Spain.

McDonald: Through my experience on the Camino de Santiago, I got the chance to feel, even if just in a limited way, what it was like to go from being confined to walking to having access to a mechanized, rapid mode of transport. It was truly incredible. What my research has underscored is that however true that OMG! feeling was for me, it would be wrong to say that that experience was the only valid response.

For example, in the early 1900s in Japan, as cities supported the expansion of street cars, it came at the expense of people who made a living operating other existing modes of transport. As streetcar riders in Tokyo experienced a revolutionary mode of travel, many rickshaw pullers were furious that the government had materially assisted the spread of streetcars by granting private companies the right to lay track on shared roads. The rickshaw pullers had reasonable complaints about the use of public resources. Yes, more people could get a ride more cheaply with the streetcars, but it’s really more accurate to think of that change as benefitting a specific group of people rather than society at large.

It’s easy to get fixated on the consumer benefit.

The idea that transport improvements benefit everyone, even if they concretely harm certain categories of workers, is quite common now and has been used to justify a variety of transportation policies in Japan since the early 20th century. And often, the companies promoting these new modes or systems are the most vocal about their universal benefit.

Part of what I want to do with my research is to draw attention to the ubiquity of this rhetoric and to suggest how we might approach the question of transport change and social benefit differently.

Aside from that Camino experience, was there another point of inspiration or discovery that also helped plant the seed?

I came to the topic while researching my first book, “Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan” (University of California Press, 2017), about how the imperial tourism industry in colonized Korea, Taiwan and Manchuria tried to teach Japanese travelers that these colonized lands were legitimately part of the Japanese nation and its territory.

In Taiwan, Japanese tourist guidebooks from the 1920–30s often highlighted Taiwan’s network of hand-pushed railcarts. Japanese travelers' accounts suggested that riding the carts took them back in time to a less-advanced civilization. In fact, the railcarts in Taiwan started more or less at the same time as Japanese colonialism, circa 1895, and the network actually got much bigger due to the economic demands that the Japanese colonial government made on Taiwan's resources and residents. The hand-pushed carts weren't a residue of the precolonial past — they were absolutely a part of the colonial, capitalist present. Travelers were not only inventing stories about the meaning of these devices in Taiwan; they were also simultaneously forgetting that human-powered railways and carts still operated in Japan.

It seemed as if there was an accepted story that human power in transport meant that a place lacked development, and then there was the actual reality of human power in transport, which existed all over, including in places that claimed to be “advanced.”

As usual, there was a lot more going on than the “accepted story.”

The goal of this project is to make us look at transport differently. It’s very easy to think of transport in terms of a device, such as a rickshaw or train. What I want people to see is the human power at every stage. And not just any kind of human power; at every stage there’s human labor, occupation and livelihood. For 100 years there’s been the argument that we have to upgrade our technology and get rid of human power, yet we still have human power, and many of these jobs are considered expendable and performed by people who aren’t treated well.

What is the history telling you as you continue to research, draft and fine tune the book? What are your conclusions?

In short, don't believe the hype! Despite all of the promise of automation in transport, human power isn't going away — at least not any time soon. I'd like to think that the more we do as citizens to think about the idea of social progress from the perspective of producers of transport rather than just as consumers of transport, the more humane our laws and policies will be.

And — perhaps this is too cynical — but since the 1970s, at least in Japan, there has been a lot of discussion about how we as consumers of transport are also trapped in the world that utopian thinking about transportation improvements created, with long commutes, traffic, shrinking public transport network services and climate change. What if we stopped thinking about "faster, cheaper" transport as social progress and started thinking about it as a series of tradeoffs that benefited certain classes and groups of people at the expense of others? I think this opens up the door for a conversation about what we want the social role of transportation to be in the future. How do we make these industries work for consumers and producers?

Keith Hamm

Social Sciences, Humanities & Fine Arts Writer

keithhamm@ucsb.edu