Revealing Images of a Revolutionary Era

The counterculture era of the late 1960s and early 1970s is gradually fading into legend, sustained by hazy memories and secondhand stories. To get a better idea of how utopian visions clashed with on-the-ground reality, contemporary photographs created by a sympathetic yet discerning artist would be enormously helpful.

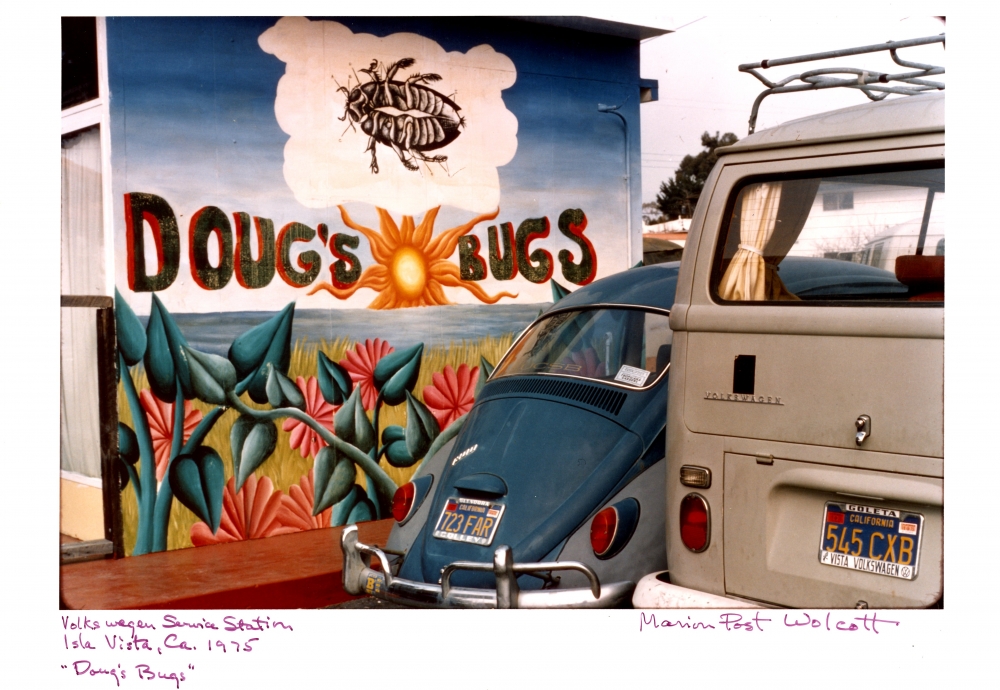

That’s exactly what the UC Santa Barbara AD&A Museum is offering with its current exhibit, “Isla Vista: Resistance and Progress by Marion Post Wolcott.” It consists of 17 photos by the veteran photographer, an on-and-off Santa Barbara resident, which document aspects of life in the university-adjacent community, circa 1974.

“Marion Post Wolcott's photographs documenting Isla Vista in the 1970s are a testament to the pioneering, counter culture ethos of this unique student enclave,” said museum director Gabriel Ritter. “Walking through the exhibition, one is reminded of the raucous spirit, and ecologically-conscious mindset that was nurtured here in the past, and remains alive and well today.”

Indeed, in her vivid photographs, Post Wolcott “brings to the fore the bright, human side of the neighborhood in the mid-1970s,” said Silvia Perea, curator of the museum’s architecture and design collection. She notes the images feature “pacific demonstrations, family-oriented fairs, organic restaurants, recycling fields, street markets,” but avoids darker elements of the time such as drug trafficking.

“While she identifies with Isla Vista’s political drive,” Perea said, “she is more attracted to the neighborhood’s achievements than to its struggles.”

Post Wolcott is best known for the many photos she took between 1938 and 1941 in the Southern U.S., when she was working for the Farm Security Administration. Rather than concentrating exclusively on Depression-era poverty, she “captured both sides of the United States’ socioeconomic spectrum, combining heartening scenes of endurance with discomforting images of privilege,” Perea noted.

Once that project ended, Post Wolcott took a nearly three-decade hiatus from professional photography, as she accompanied her diplomat husband to various postings around the world. They settled down in Santa Barbara in the early 1970s, and in a visit to Isla Vista, she found inspiration to resume her work.

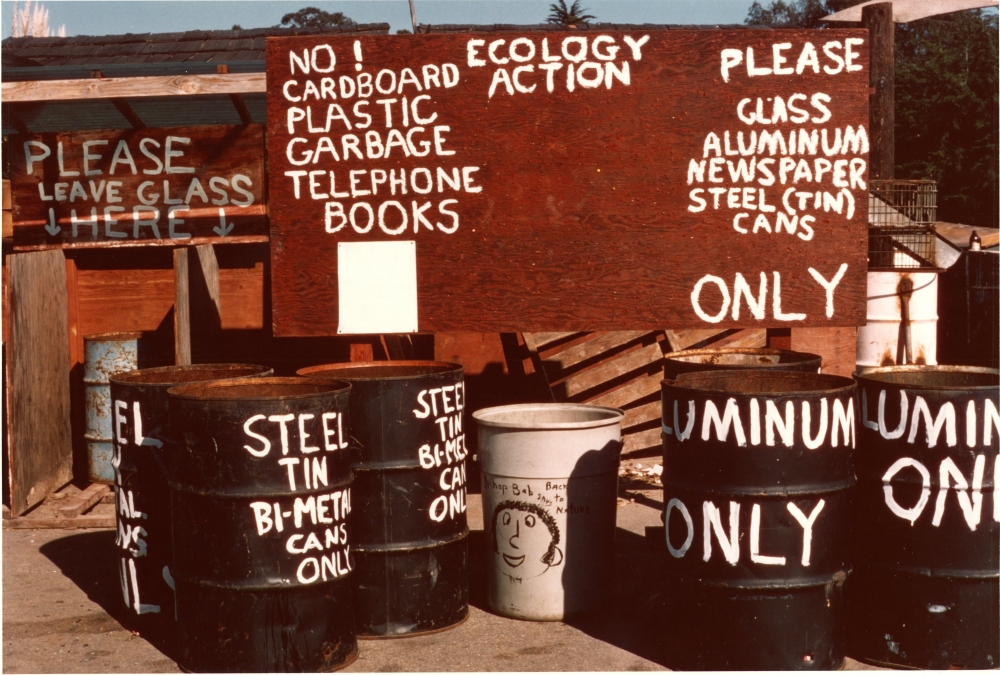

When she turned her lens to Isla Vista, Perea noted, she generally focused on “details, rather than panoramic views — a hand-lettered get-out-the-the vote sign; a group of musicians playing at an outdoor concert; a bearded, shirtless man with a young child on his shoulders. Several of the photographs document Isla Vista’s recycling program — one of the first in the nation — showing, among other things, huge plastic bags full of collected cans.

“Just a few years before, in 1969, the oil spill in the Santa Barbara channel had spurred wide ecological action locally and nationally,” Perea noted. “Post Wolcott’s photographs attest to the lasting social mobilization that followed the disaster. The handmade graphics in the recycling bins and fields highlight that ecological action at Isla Vista was driven by local residents,” as opposed to a government agency.

Stylistically, Perea sees more similarities than differences between these photos and the better-known ones Post Wolcott took during the Depression. “The FSA series is shot in black and white and questions ideals of democracy in a capitalist society, while Isla Vista is in color and praises the progress that stems from selfless human bonding,” she noted.

“However, the casual, fine-art approach to her subject matters remains consistent. Both series are also fruit of Post Wolcott’s belief in the power of photography to drive socioeconomic and political progress.”

The photographs were originally from the collection of Post Wolcott’s daughter, Linda Wolcott Moore, who owned a San Francisco gallery specializing in photography. Like her mother, she, too lived in Santa Barbara for a time, and when she moved out of the city, she donated the photographs to the AD&A Museum. A few of them were shown at a retrospective exhibition of Post Wolcott’s work at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1988, two years before the artist’s death. This is the first time the entire series is on display.

“As I see it, the Isla Vista series is, ultimately, a self-portrait of Post Wolcott,” Perea said. “In I.V., she finds the social values she upholds since young, and that her work for the FSA in the 1930s and 40s reflects. By immortalizing expressions of these values decades later, Post Wolcott is defining who she is, not only as an artist, but also as a human being, all the while celebrating her regained freedom to do so.”

“Isla Vista: Resistance and Progress” continues through May 1 at the AD&A Museum, 552 University Road. It is open from noon to 5 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday. Admission is free. For more information, call (805) 893-2951, or go to museum.ucsb.edu.