Fresh Eyes on the New Deal

Three months after Donald Trump kicked off his presidential campaign with a ride down a golden escalator, dozens of scholars gathered at UC Santa Barbara for a major conference that would take a new, interdisciplinary look at the legacies of the New Deal.

The conference was so successful it generated two books of essays by distinguished scholars. The first, “Beyond the New Deal Order: U.S. Politics from the Great Depression to the Great Recession” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), took a fresh look at the New Deal’s political impact and the neoliberalism that followed. It was edited by Gary Gerstle, Nelson Lichtenstein and Alice O’Connor. Lichtenstein and O’Connor are members of the UCSB Department of History.

The second, “Capitalism Contested: The New Deal and Its Legacies” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), edited by Romain Huret, Lichtenstein and Jean-Christian Vinel, argues that despite decades of intense political and economic hostility, New Deal ideas, values, laws and institutions remain at the heart of American politics and partisanship.

Six years after Trump’s escalator ride, the programs and reforms enacted in the Franklin Roosevelt administration are once again a hot topic. President Joe Biden is calling for a new New Deal to address climate change, a crumbling infrastructure, race and class inequality, corporate monopolies and more.

“The idea for these books came just as Trump was coming in,” said Lichtenstein, who retired last year as UCSB distinguished professor of history. “We had no idea that Vice-President Biden would occupy the Oval Office and seek to recast and expand many of the historic New Deal programs. We obviously didn’t know that.”

And yet the timing of the books has been uncanny. Lichtenstein said there’s a robust debate, not just among historians, but in Congress: What is useful to take from the New Deal and what is not?

“At the time of the conference many participants saw the Obama presidency as a disappointment, and of course, many would come to see Trump as a threat to the entire New Deal legacy,” he said.

But, Lichtenstein added, the COVID pandemic highlighted the importance of an updated New Deal-style welfare state, with income supports for the working poor and a vastly expanded system of health provision.

“I think the brunt of both these books is that we definitely still live in the shadow of the New Deal, and we’re still fighting about many of the same issues that were put on the agenda 80-odd years ago.”

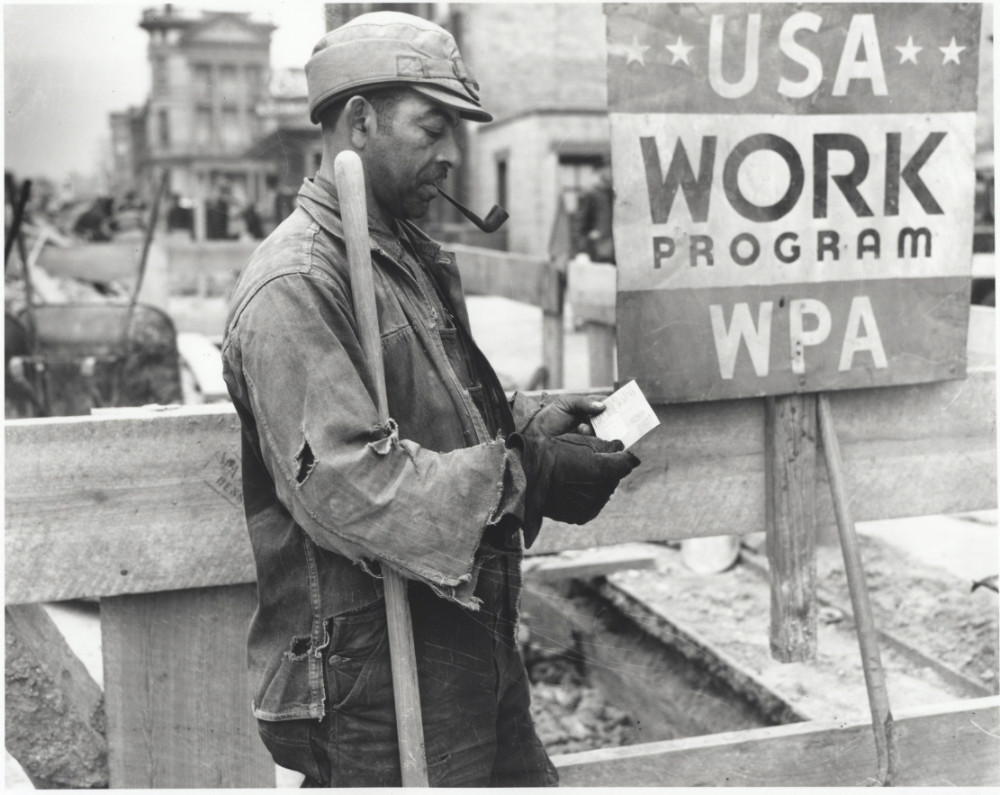

While the original New Deal was intended to improve the lot of ordinary Americans, Lichtenstein notes that when it came to issues of racial and gender equality it proved “oblivious, disastrously inadequate and retrograde.” Historians and other scholars have known this for decades, which is why many now see the era of social reform in the 1960s as a way to bring under the umbrella of the New Deal people of color and others whose interests were neglected in the 1930s.

“Domestic workers, for example, or hospital and farm workers, who had lacked minimum wage and Social Security coverage are brought in during the 1960s,” he said. “And of course, the Black Lives Matter protests demonstrate that that work is far from done.”

Now Biden is trying to include those still left behind into the New Deal order, with what Lichtenstein defines as a suite of programs and policies that generate a new/old ethos on how government policy can reshape social and economic life.

“We call the New Deal an ‘order’ ” he said, “which means you have a welfare state, you have an organized working class, you have a degree of economic regulation, you have parties that are really shaped from the New Deal moment. That’s what I mean by the phrase ‘New Deal Order.’ ”

Of particular interest in addressing the New Deal, he said, is labor, which he called “one of the fundamental building blocks of a New Deal order. The labor movement was the foundation stone of the Democratic party. And that was true for decades. And of course it’s become much weaker.”

Today union membership is no higher than 10% of all workers, he noted, while at its peak in the 1950s 35% of all non-farm workers were enrolled in trade unions.

Given the global political developments of the ’30s, Lichtenstein said, the New Deal was a beacon of hope.

“The New Deal was not just about economic revival, but about democracy, about preserving democracy and in a world of dictators in the ’30s,” he said. “And people looked to the U.S. This was kind of the only viable alternative to communism or fascism in the ’30s. Should America once again revive a robust domestic New Deal, that same global dynamic could work today.”