An Enduring Connection

In the early 1980s, José Cabezón was the Spanish translator for His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama, translating for him in Spain, Costa Rica, Mexico and, on a few occasions, in India. As a result, he became a lifelong student of the Dalai Lama.

The connection endures.

Cabezón today holds the Dalai Lama Endowed Chair in Religious Studies at UC Santa Barbara, which recently marked the 20th anniversary of that endowment. In a nice complement to the milestone, the university’s Arts & Lectures program on May 18 will host a virtual conversation between His Holiness and author Pico Iyer. Beginning at 8:30 p.m., it is the keynote event in Arts & Lectures’ yearlong “Creating Hope” initiative.

The event may be viewed via livestream on YouTube and on the Arts & Lectures Facebook page. A recording will be available for unlimited replay on the Arts & Lectures website.

“The Dalai Lama has made many visits to the university over the years,” said Cabezón, who first joined UCSB in 2001. “The chair was created by friends of His Holiness in part as the result of a long connection to the university. Almost all the donors were local. They wanted to honor him by establishing UC Santa Barbara as a site where Tibetan Buddhism was taught.”

And so they did. The Tibetan Buddhism program is part of UCSB’s emphasis in Buddhist Studies, in which both undergraduate and graduate students can specialize.

“The establishment of the XIV Dalai Lama Endowed Chair in Tibetan Buddhism and Cultural Studies and the arrival of Professor José Cabezón, one of the leading international scholars in Tibetan Buddhism, as the first chairholder was a momentous event in the Department of Religious Studies,” said Fabio Rambelli, professor and chair of religious studies. “Under Professor Cabezón’s leadership, Tibetan studies, and Buddhist studies more generally, have become central fields and representative components in our department — strongly rooted in a specific tradition and geographical area but at the same time in constant conversation with the field of religious studies at large and open to cutting-edge theoretical approaches.”

Distinguishing UCSB’s program, according to Cabezón, are its four professors specializing in different areas Buddhism, and its commitment to teaching the necessary languages, including Sanskrit, Tibetan, Chinese and Japanese.

“Our goal is to create well-rounded scholars of Buddhism,” Cabezón said. “At the graduate level, this means that students choose one major area — Tibetan Buddhism, for example — and a minor area, say Indian or Mongolian Buddhism, and one other religious tradition outside of Buddhism. They acquire the necessary languages and methodological tools to do independent research, and they spend time, usually at the dissertation stage, doing field research in an Asian country so that they get a sense of the cultural context and lived religion of the form of Buddhism they are researching.”

It has not come without its challenges.

As with the humanities broadly, fields within religious studies have seen a “retrenchment,” Cabezón said, “as graduate students consider the not-so-rosy and increasingly competitive outlook of the academic job market, and as undergraduates choose seemingly more ‘practical’ majors, not realizing the many possibilities that the study of the humanities open up.”

Over the program’s two decades, Cabezón himself has mentored fourteen Ph.D. students. Among those who have already completed their degrees, there are university professors; an editor for the “84,000 Project,” which aims to translate the entire 108 volumes of the Tibetan Buddhist canon into English; and one working for a nonprofit that funds Buddhist scholarly projects. That’s only a sampling.

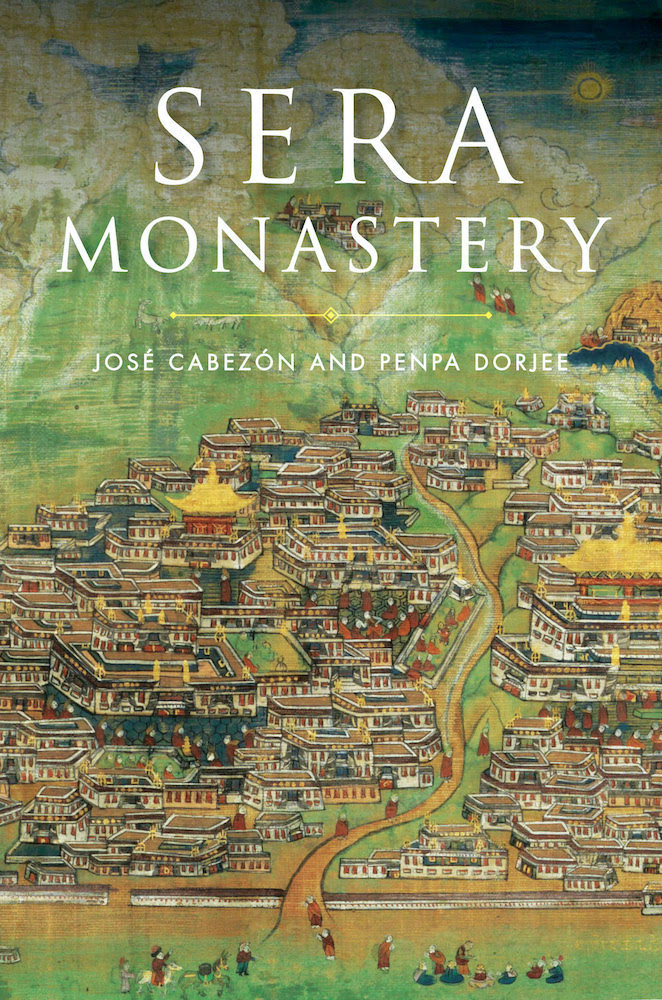

Much of Cabezón’s own scholarly work has focused on Sera Monastery, founded in 1419. One of the three great seats of learning of the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism, Sera had more than 9,000 monks in residence in 1959, and was the second largest monastery in the world.

Cabezón lived and studied at Sera during the period from 1980 to 1985, and in 2019 he and co-author Penpa Dorjee, associate professor and head librarian of Shantarakshita Library of the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies in Sarnath, India, wrote the book “Sera Monastery” (Wisdom Publications) in recognition of its 600th anniversary. “Penpa and I both studied at Sera and we thought to write this history in part as a way of giving something back to an institution that has been so influential to our identity as scholars,” Cabezón said.

Funded by a Guggenheim Fellowship and by an American Council of Learned Societies/Ho Collaborative Research Fellowship, the book draws on Cabezón’s earlier research but also contains a completely new narrative history of the monastery from its founding to present day.