Plot Twist

The black rats weren’t supposed to be there, on Palmyra Atoll. Likely arriving at the remote Pacific islet network as stowaways with the U.S. Navy during World War II, the rodents, with no natural predators, simply took over. Omnivorous eating machines, they dined on seabird eggs, native crabs and whatever seed and seedling they could find.

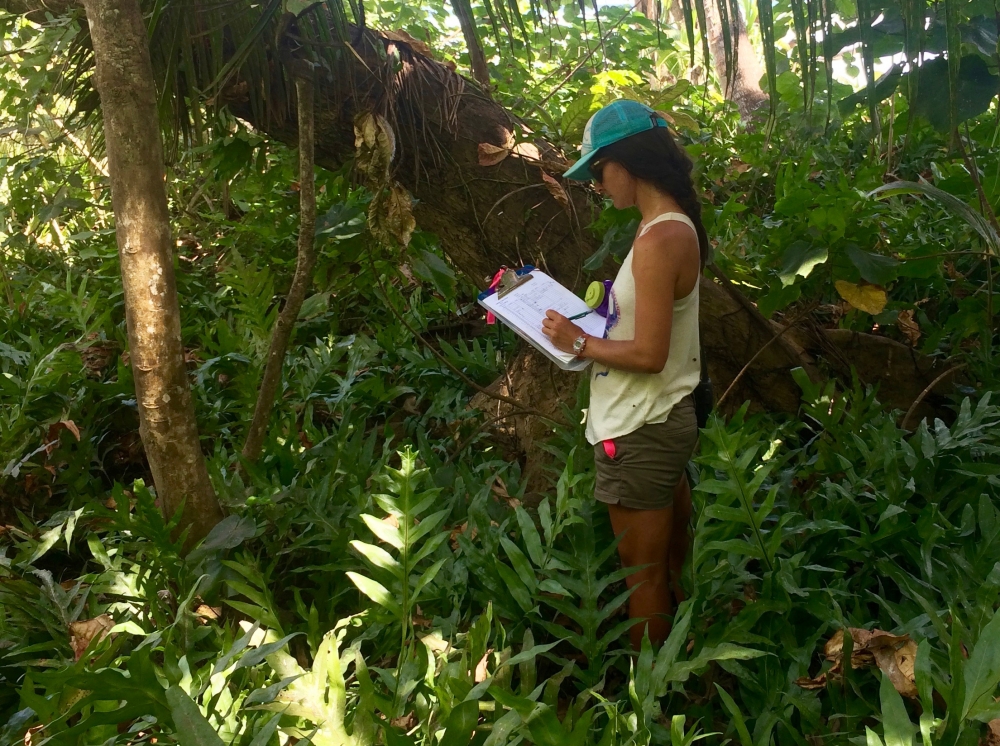

When the atoll’s managers — the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy and Island Conservation — were planning to conduct a rat eradication project, UC Santa Barbara community ecologist Hillary Young and her research group saw it as an unusual opportunity. They had already been visiting Palmyra regularly to track another non-native species — the coconut palm — to see whether it was spreading invasively in the area, potentially impacting the nesting seabird population and changing the island’s soil composition. They had plots where they were monitoring trees in various stages of growth and survival; how would the vegetation respond to the eradication of the island’s main seed and seedling eater?

“Prior to the eradication, most of the understory of Palmyra was either bare ground — sandy soil or coral rubble — or covered in a carpet of ferns,” said Ana Miller-ter Kuile, a graduate student researcher in the Young Group and lead author of a study that appears in the journal Biotropica. The rats were quick to eat seeds and young plants coming out of the ground, and they frequented the canopy as well, often nesting in the coconut palms and eating coconuts.

Eradication of the rats — which was conducted in 2011 — did in fact result in a resurgence of vegetation on Palmyra. And not only that. The Asian tiger mosquito was wiped out, while two species of land crab emerged, adding to the atoll’s biodiversity.

But rarely is ecology easily untangled. In the years that followed eradication, Palmyra’s understory did indeed fill with juvenile trees as seeds that hit the ground were allowed to take root. Only they were often not the Pisonia or other native trees that would have been the more ideal forests for the native seabirds and animals of Palmyra.

“I was on the island in 2012, just after the eradication and could easily navigate through the open jungle understory,” Miller-ter Kuile said. “Two years later when I went back, I was wading through an infuriating carpet of seedlings that were taller than me, tripping over piles of coconuts.” While the researchers found a 14-fold increase in seedling biomass, most of these new seedlings were juvenile coconut palms, their proliferation left unchecked by the removal of the rats.

“Rats were basically eating almost every nut before it even reached the forest floor,” Miller-ter Kuile said. “I knew that rats could have an impact, I just didn’t expect it to be this large.” In the absence of rats, according to a population model the researchers built based on a decades’ worth of data on coconut seed production, growth and survival, the coconut palms’ population growth rate increased by 10% — enough to eventually overtake the island, had the managers not stepped in with an aggressive coconut palm removal project.

The coconut palm invasion is a problem for places like Palmyra Atoll, as it shifts the island’s ecology away from native plants and animals.

“Coconuts have a very different ‘nutritional’ profile from the native tree species on this island, with much more carbon and less nitrogen,” Miller-ter Kuile said. “When these trees die, because they have different nutrient profiles from native plants, they are likely to break down differently — and more slowly — and influence rates of decomposition.” In addition, she said, native seabirds do not nest in coconut palms, which would deprive the atoll of the nutrients in their guano, which, in turn, “would lead to what would likely be a fairly nutrient-poor system, which discourages other native plants from growing in those areas.”

Continuing their restoration of the island, Palmyra’s managers were working to remove the vast majority of the island’s millions of coconut palms to give local species a chance to dominate, a project that is currently on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anticipating the indirect downstream effects, such as potential shifts in ecology toward other invasive species, could become part of a more holistic island rodent eradication effort, Miller-ter Kuile said.

“Wildlife management, in particular, has a history of being single-species focused, which often means that a lot of time and energy is put into producing or controlling a species without considering the broader effects of that management effort on all of the rest of the species in that ecosystem,” she said. According to the study, “documenting the variation in invasive rodent diet items, along with long-term surveys, can help prioritize island eradications where restoration is most likely to be successful.”

“The ‘accidental experiment’ of our long-term monitoring of trees in this project I think provides a rare opportunity to quantify the immediate and longer-term effects of eradication,” she said.

Research in this paper was conducted also by Devyn Orr, An Bui, Maggie Klope, Douglas McCauley and Carina Motta at UCSB; and Rodolfo Dirzo at Stanford University