A Sea Change

When Google mapped parts of the ocean for its Underwater Earth, it used the same technology, essentially, it employed for its Street View application. Melody Jue finds this odd.

An assistant professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, her research focuses on the ocean and environmental humanities, particularly in how it’s portrayed in the media. Underwater Earth and its drive-by view of the sea, Jue said, betrays what she calls a “terrestrial bias” — the idea that the ocean can be represented in the same ways a land environment is.

Jue explores this and more in “Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater” (Duke University Press, 2020), a thoughtful and deeply researched dive into the ways humans approach the ocean in film, art, literature and technology.

“One aim of the book,” she said, “is really to ask, How have we created media and representations of the ocean? How has that reflected terrestrial bias and what can we do? What can we do differently?” To answer these questions, “Wild Blue Media” discusses a wide variety of media, including science fiction literature, underwater memoirs, documentary film, data visualizations and underwater artwork.

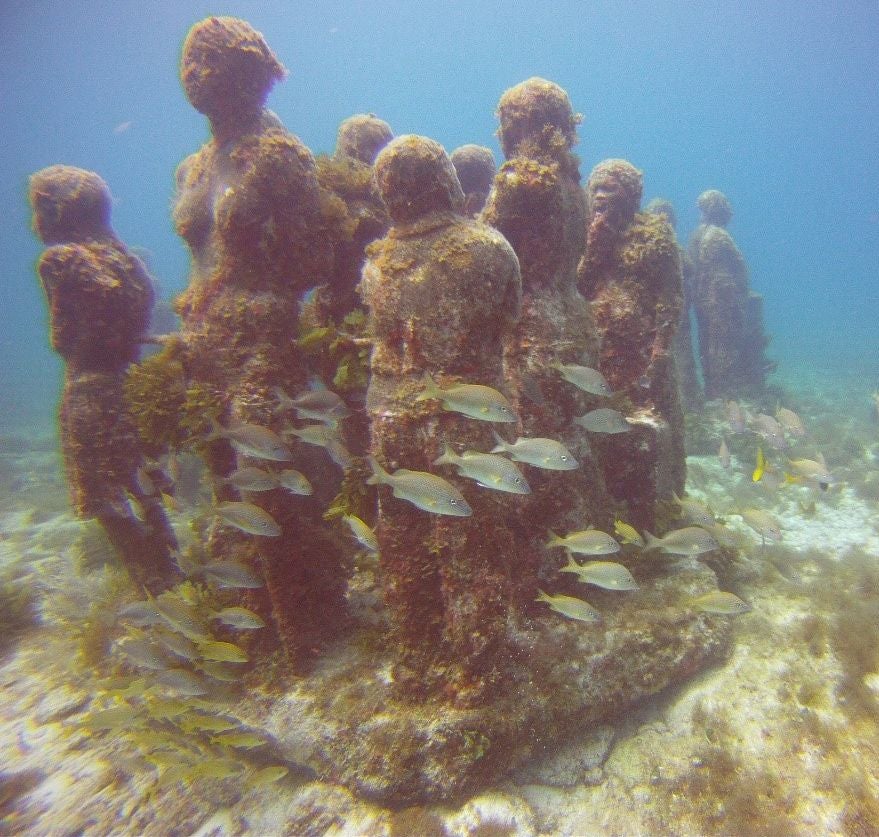

In one chapter of the book, Jue, a diver, examines two aquatic museums: Jason deCaires Taylor’s Museo Subacuático del Arte (Underwater Museum) off Cancun, Mexico, and Dos Ojos (Two Eyes) in a cenote, or underwater cavern, in Yucatán.

Taylor’s museum consists of a number of human figures arrayed in 30 feet of water. The sculptures grow and change over time as life forms such as coral eggs, carried by seawater, attach themselves and transform the human forms into something “somewhat uncanny, with eyes closed and no evidence of breathing — perhaps asleep, resting, or even ghostly,” as Jue writes.

The museum, she said, questions how interpretation takes place differently underwater. In a terrestrial museum, the objects are fixed and no one expects them to change over time. Taylor’s figures, though, experience a kind of metamorphosis that challenges the viewer in three dimensions.

“So instead of a museum that’s about preservation, you have a museum that’s about change,” Jue said. “And as a visitor when you try to navigate it, I found that it was actually really difficult to hover, to stay put because of the current at the time. And so it would kind of push me to the side and it was actually easier to swim over the sculptures than to look at them face to face.”

In photos of the exhibits Taylor posted, the sea was clear and the figures faced the camera, a traditional orientation known as frontality. When Jue visited the water was cloudy.

“I realized that the artist was selecting for conditions where even though the sculptures were underwater, he wanted them to be colorful, clear, populated through a face-to-face orientation,” she said. “So this led me to think, ‘Wow, undersea environments provide different conditions for thinking about the museum and its mission, and also for interpretation, because of where the ocean positions you as an observer.’ ”

The Dos Ojos cenote, on the other hand, boasts no human-made sculptures. Diving there was a spatial experience, constantly adjusting for buoyancy and depth. She called it “a descent into another dimension; within the caverns, one can still pass into yet more dimensions through encountering new bodies of water.”

“That’s why the field work of scuba diving was really important for me,” Jue said, “because I began to think about how am I interpreting things underwater differently than on land. So each chapter really just takes on a facet of this question: What can you do with a submerged perspective and what are the media or literature that has tackled this question? And it really looks to be of interest to artists, to writers who think, How does that underwater change point of view?”

The sea, covering 70% of the Earth’s surface, has always been one of humanity’s great mysteries and paradoxes — the giver of sustenance, the taker of lives. Jue wants us to see it anew.

“I hope that [the book] encourages people to imagine differently when they look at or experience the ocean through media or immersion or other kinds of things,” she said. “I hope that they come away with some ideas for how they might write stories differently or create media differently. And it’s pretty open ended.”