Freed by the Spirits

In the West, said Roberto Strongman, an associate professor of Black Studies at UC Santa Barbara, human existence has long been something of a trap: The self is the body, and gender is binary.

“The traditional sense of the relationship between the body and the soul or the anima is that we are living in a corporeal case,” he said. “And that has some consequences that are troubling. The first and foremost is that it posits our existence as a kind of imprisoned existence. We are bound. We are encased and we only have to look forward to the moment of our death to be released from that.”

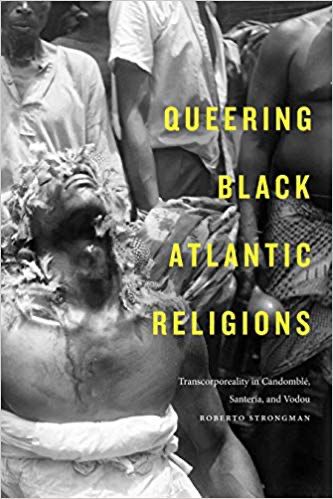

In his new book, “Queering Black Atlantic Traditions: Transcorporeality in Candomblé, Santería and Vodou” (Duke University Press, 2019), Strongman argues that certain rituals in these African diasporic religions liberate participants from the constraints of the body and touch the divine.

Strongman defines transcorporeality as “the distinctly Afro-diasporic cultural representation of the human psyche as multiple, removable and external to the body that functions as its receptacle.”

“I think that the most important idea that I would want for readers to take out of the book,” he said, “particularly readers who are not academics, is the ways in which we conceptualize the relationship between the material aspects of the self, like the body, and the immaterial aspects of the self — things that we call the mind or the soul.

“And it’s not the same across all peoples and all times,” Strongman continued. “In fact, there’s a great deal of metaphor, symbolism and analogy that comes into trying to understand what those parts are and how they interact with each other. And so there’s a liberatory potential in seeing the relationship between the body and the soul as constructed and unmoored.”

As Strongman describes in his book, transcorporeality is first achieved by neophytes in initiation spaces — “the djevo of Haitian Vodou, the camarinha of Brazilian Candomblé, or the igdobú of Cuban Lucumí/Santería” — where they will “mark the death of the old, illusory self and foster the rebirth of the new, spiritually aware subject.”

It is in these places of “humility,” where initiates meditate in seclusion, interrupted only by priests and elders who tend to their physical needs, that they hear the voices of the West African divinities known as orishas and their bodies become open to possession. Many African communities have long conceived of the body as an “open vessel that can be occupied temporarily by a variety of hosts,” Strongman writes.

Because of this, he said, “when the divinity comes in the ritual space, then it’s able to dislodge that external immaterial self and substitute it with itself.” This “trance possession,” he explained, offers two benefits: liberation from the body and “the possibility for identification with the external divine.”

The latter is possible because the divinities that displace the self in the body are of multiple genders. That fluidity can allow the external self to experience a different sexual identity — one that could feel like a more authentic self, Strongman explained.

“I think that this metaphorical representation of the self becomes of interest to people who may have a very different relationship to their bodies,” he said, “who may feel like their bodies are not ultimately speaking truly to who they are and that there might be some sort of discrepancy, perhaps, between their sense of self and their bodily reality.”

The relationship between the soul and body, he added, “is not as fixed as we might think that it is, but it relies a great deal on imagination, projection, metaphor and self-understanding.”

Transcorporeality, and its sense of selfhood being external to the body, also highlights the way Americans in particular view an alternative sexual identity as something that has to be released, according to Strongman.

“Think about all these metaphors of ‘in-and-out’ underpinning queer identities in the U.S.,” he said, “that prompt people to feel that they have to come out.”

“That is not in the vocabulary of non-heteronormative identities in many parts of the world and in parts of the black Atlantic,” Strongman added. “Nobody there has to come out because they would be coming out from where? And nobody has to make a formal declaration. Nobody has to make some sort of profession of sexual orientation. It just is; sex and gender practices and identification become evident in your everyday interactions with people. The realization of orientation emerges in a very natural way.”