In the Wake of Art

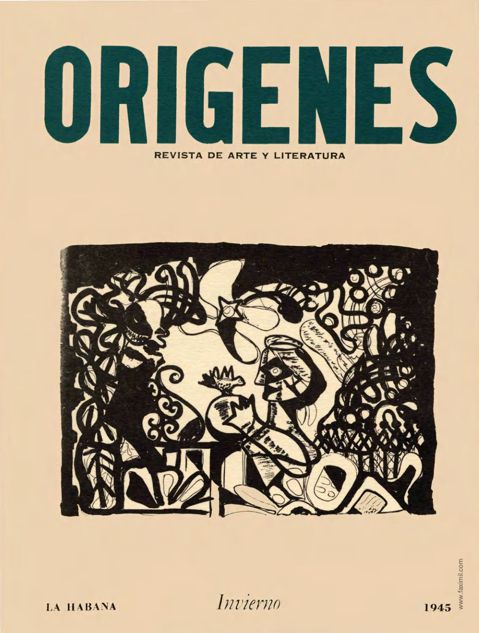

From 1944 to 1956, the Cuban journal Orígenes was the most important arts and literature periodical in the Spanish-speaking world. Co-edited by a pair of cultural luminaries, José Lezama Lima and José Rodríguez Feo, the publication featured a cosmopolitan array of contributors: Cuban writers like Eliseo Diego and Virgilio Piñera, Mexican poet Octavio Paz, American poet Wallace Stevens and many others.

Orígenes (origins) was credited with disseminating the work of James Joyce in the Spanish-speaking world. Women also played a major role in the journal. It featured contributions by poet Fina García Marruz, ethnographer Lydia Cabrera, visual artist Amelia Peláez and Spanish philosopher María Zambrano.

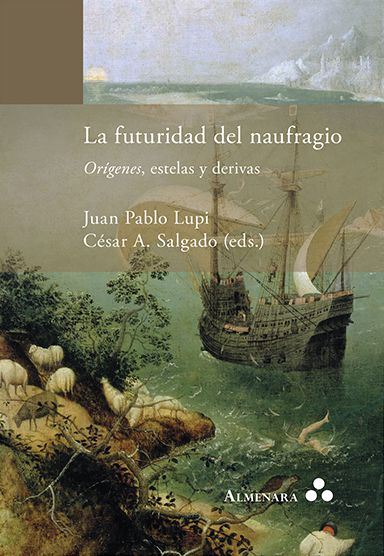

Now, 63 years after its final edition, the journal is the subject of a new collection of essays, “La futuridad del naufragio: Orígenes, estelas y derivas” (Almenara, 2019), co- edited by Juan Pablo Lupi, a UC Santa Barbara associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese, and César A. Salgado, an associate professor of Latin American studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Translated as “The Shipwreck’s Futurity: Orígenes, wakes and drifts,” the book’s 12 essays critically examine the traditional interpretations of the journal’s legacy and transformation from literary touchstone to forgotten relic to revolutionary symbol of Cuban national character.

Viewed as a whole, the collection shows how those interpretations have been misleading and reductive, Lupi said. The Orígenes project was not apolitical, nor was it strictly an artistic or nationalist endeavor. It has, in fact, always been a subject of argument and critique, he said. Multiple and even contradictory forces converged in its production and its reception.

Indeed, the journal’s complexity, contradiction and contingency are what have imbued it with a sense of futurity — a non-linear history subject to unpredictable contingencies — and of shipwreck, what Lupi calls “the unforeseen, often disastrous, deviations from what we understand the ‘future’ will be like.”

It’s been a fraught journey for Orígenes, Lupi said. He noted that in the 1960s and 1970s, most of the writers associated with it were silenced and ostracized by the regime of Fidel Castro. The journal was seen as counterrevolutionary, and was treated as though it never existed. Lezama Lima, who died in 1976, spent his final years in his home, a political pariah.

But in the 1980s, a younger generation of Cuban writers, born after Castro’s ascendance in 1959 and tired of socialist realism, began to look back. They gravitated toward the writers associated with Orígenes, which enjoyed a resurgence.

“In some ways, the journal had more impact in the ’80s and ’90s than it did in the 1940s and ’50s,” Lupi said. Authors like Lezama Lima and Piñera, he added, “at the turn of the century became the most influential Cuban writers.”

The Cuban government took notice. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the island’s chief benefactor, the Castro regime began to shift the public narrative from socialism to nationalism and some intellectuals promoted Orígenes as an icon of national identity, Lupi said. “This cooptation of Orígenes by the state was very controversial,” he noted.

Cintio Vitier, a prominent writer who was associated with the journal, claimed that the Orígenes project “was an expression of some type of national essence or historical destiny,” Lupi said. What emerged were dueling narratives about Orígenes: Was it an apolitical “art for art’s sake” journal? Was it a nationalist expression? Or was it — as Lezama Lima had originally envisioned it — a project of “resistance” and redemption through art and literature?

“One of the things we wanted to do in this project was to critique and undo these traditional readings,” Lupi continued. Looking at the “wakes and drifts” of Orígenes may teach us important lessons about the role of art in times of political and civic crisis.

A unique feature of the book is the prologue. Split into two “wakes” — Salgado on “futurity” and Lupi on “shipwreck” — the essays are meant to be read together: Start with “futurity” on the left page, then begin “shipwreck” on the right. Turn the page and repeat.