Next-Gen Strategic Thinking

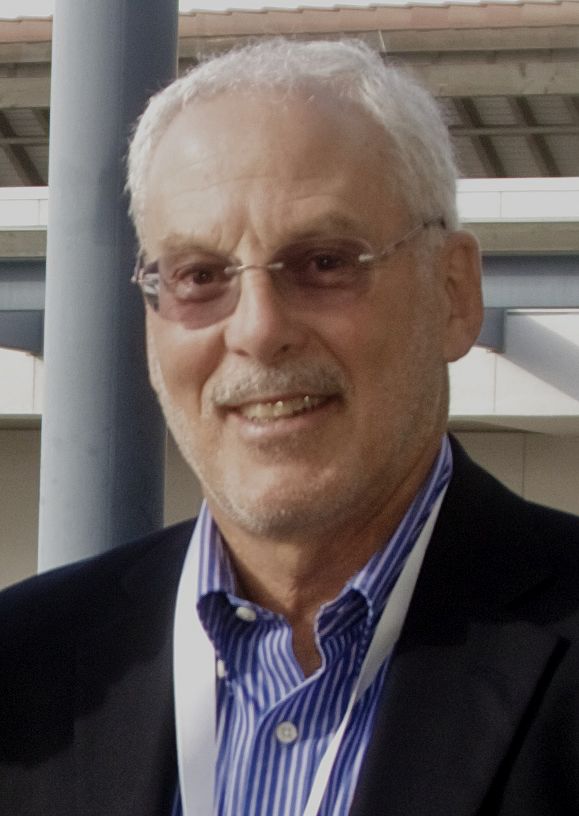

Michael Krepon had no idea that his guest appearance at UC Santa Barbara would be so timely. A co-founder of the Stimson Center, one of Washington’s top think tanks, Krepon was invited to campus by Neil Narang to speak to his class about nuclear security in South Asia. Just two weeks earlier, India and Pakistan, both of whom possess large stockpiles of nuclear weapons, edged closer toward the brink of war.

For the 20 students in Narang’s “Nuclear Weapons and International Security” course, Krepon’s talk offered an important real-world glimpse into a life-and-death topic that, paradoxically, has been fading from the public’s imagination and policy priorities.

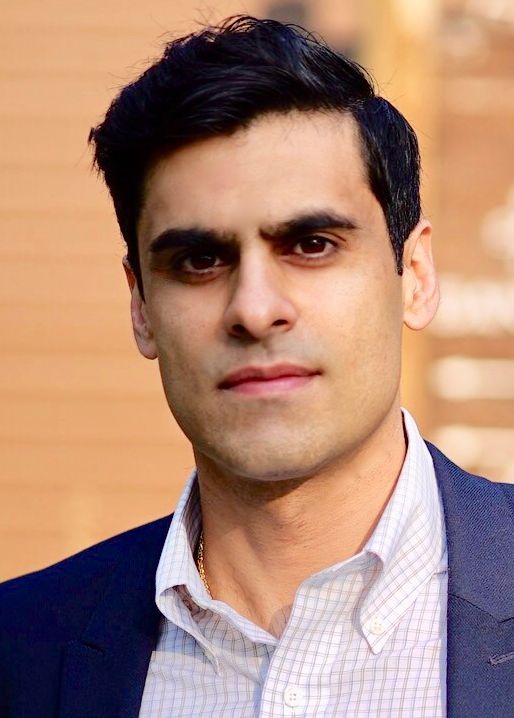

A rising associate professor of political science who specializes in global security issues, Narang saw the class as a unique opportunity to give a select group of high-achieving fourth-year undergraduates the chance to learn directly from some leading experts in nuclear security and strategy.

“I don’t think there is a single more relevant course that I can teach today,” Narang said. “In one way or another, nuclear weapons appear to be at the heart of some of the most pressing foreign policy challenges. From emerging crises with North Korea and Iran, to the rapid rise of China, to the recent breakdown of arms control agreements with Russia, nuclear weapons cast a long shadow across the headlines over the last decade. And yet, I discovered that few students knew the historical or technical background behind nuclear weapons, the patterns and forces behind nuclear weapons proliferation, or the grave consequences of these weapons for international and regional security.”

The new course originated when the Stanton Foundation approached Narang about developing a class on nuclear security, one of its philanthropic priorities. The foundation was searching across U.S. universities for exceptional instructors with expertise in the highly specialized field of nuclear security, and Narang — who served as a senior advisor in the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy on a Council on Foreign Relations fellowship — fit both criteria.

The foundation offered Narang the financial support and freedom to design his ideal course, so he requested $10,000 to fly in guest speakers from around the country. “It can be humbling to admit this, but it was important to me that the students heard from the very best scholars and policymakers on each topic, and that meant I needed to fly in some of my colleagues from other universities and the Pentagon,” he said. “I wanted to bring in the very best people on each topic.”

But there was a catch: For the foundation to agree, the university would need to match that $10,000 for three more years to support the class. But without a spare $30,000 lying about the campus, the foundation’s offer was about to disappear. And then an administrator suggested Narang approach the university’s Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies, led by director Michael Stohl. It was the right call.

“I reached out to Michael Stohl and he said, ‘Consider it done.’ ” Narang said. “He immediately recognized the value of the course and earmarked the money for three years. Thanks to Michael and the Orfalea Center, we have the funds to support the course into the future.”

Stohl even found Narang a classroom — always in tight supply on campus — for the course to meet, and he offered the support of Melissa Bator, academic coordinator of the Orfalea Center. The class, Stohl said, “creates an opportunity for us to bring in the world’s leading experts. I think it has the potential to really direct students’ attention to a crucial issue in global security. This is a problem that is not going away anytime soon. It also creates an opportunity to make the intersection of technology and social science a focal point for UCSB, because all of these experts will think of UCSB students and faculty when working on these issues into the future.”

Narang reached out to his network and ultimately hosted eight heavy hitters in the field of nuclear security. Each speaker covered a different aspect of the nuclear security problem. For example, Krepon discussed the role of nuclear weapons in the crisis between India and Pakistan. Greg Weaver, deputy director for Strategic Plans and Policy of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon, addressed how nuclear weapons can change military strategy and plans. Colin Kahl, who served as deputy assistant to President Obama and national security advisor to Vice President Biden, spoke about Iran and North Korea as emerging nuclear threats. And, for balance across perspectives, John Mueller of the Cato Institute and Ohio State University argued that nuclear weapons are irrelevant to national security.

The speakers, Narang said, bring diverse viewpoints that force his students to think deeply about nuclear issues for the first time. “They have to struggle with these opposing perspectives from equally formidable experts,” he said. “It’s amazing: I can take a poll after one class and virtually all of the students will come down one way on an issue. Then, I can take a second poll on that same issue following the next speaker, and they’ll come down on the exact opposite side. I find myself simultaneously learning a lot about how students see nuclear weapons, and what assumptions those beliefs are built on.”

But the ambition of the course — for both the foundation and Narang — is much broader than any one individual insight: inspiration. As Narang explained, public awareness about nuclear weapons reached a peak during the Cold War, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union had a stockpile of roughly 75,000 nuclear weapons between them. But the generation of experts who dedicated their careers to nuclear issues, often referred to as “Cold Warriors,” will soon be retiring. Clearly, Narang said, the field needs an infusion of young scholars and policymakers.

“I think this is a great course,” Krepon said after speaking to the class. “These problems are big. We’re going to need a new generation with idealism and energy to go along with the brains. UCSB can help.”

Krepon’s comments aren’t unique, Narang said. “Every single guest lecturer has made the same appeal without fail: an entire generation that thought deeply about nuclear weapons is ‘aging out’, and there is a worrisome skills-gap and interest-gap left behind them.”

Those gaps are what the Stanton Foundation took aim at when it approached Narang to develop the course, which provides a rare opportunity for undergraduates to participate in a graduate seminar-style class, with a small number of students around a single table discussing readings together and engaging with speakers.

Narang hopes it will lead one or two students to consider a career in nuclear policy. At minimum, though, the course appears to have opened some eyes.

“For many of these students, the course provided their very first video glimpse of a nuclear detonation, images that the preceding generation can all too easily recruit,” Narang said. “The awe in their faces when they see the size of the mushroom cloud at Bikini Atoll is inspiring. It was an important moment when I later explained that states eventually developed weapons that are many thousand times more powerful than the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, and that even after decades of arms control and reductions, states still possess roughly 15,000 of them.”

It’s enough to get the students’ attention — and interest.

“California can seem really remote from Washington D.C., so many of our students can feel like they are precluded from participating in these debates,” Narang said. “So to have high-ranking policymakers come and speak about their career trajectory, talk about their pathways into the federal government and think tanks is really invaluable. Invariably, each speaker said, ‘You can do this. D.C.’s right there and here’s my email address; let’s go.’ ”