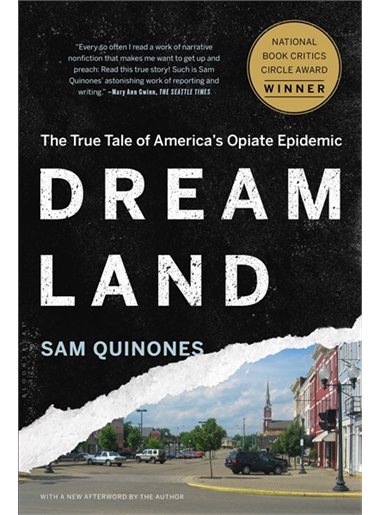

Dreamland

The opioid epidemic sweeping across the nation has redefined what it means to be an addict in America.

From 1999 to 2016 more than 200,000 people have died from overdoses related to prescription opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control. And the number of people addicted is more than 10 times that.

With prescription pain relievers in the mix — oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine and morphine, among others — drug dependency now reaches every socioeconomic stratum. Middle- and upper-class suburban families, senior citizens and straight-A students are falling victim to addiction’s downward spiral.

And that’s not counting those who turn to heroin when their legally prescribed drug of choice becomes unavailable.

Shining a light on the crisis

Los Angeles-based freelance journalist Sam Quinones, who delves into the crisis in his award-winning book, “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic,” will discuss the origins of our nationwide opioid epidemic in a talk at UC Santa Barbara Thursday, Feb. 1.

“Dreamland: America’s Opiate Epidemic and How We Got Here,” is part of the UCSB Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s (IHC) yearlong series Crossings + Boundaries. Free and open to the public, the talk begins at 4 p.m. in the campus’s McCune Conference Room, 6020 Humanities and Social Sciences Building.

“In planning ‘Crossings and Boundaries,’ it was impossible not to think about the interstate and transnational border crossings that are contributing to today’s opiate epidemic,” said IHC Director Susan Derwin. “With the talk by journalist Sam Quinones, we hope to bring this situation further into the public eye.

“Quinones is an extraordinary story teller,” she continued. “His book shines a light on the forces and places enmeshed in the culture of opiate dependency — from pharmaceutical laboratories and organized medicine in the U.S., to poppy growers in Northwestern Mexico, to American suburban mothers, high school athletes, and people living in the Rust Belt.”

The neurobiology of opioid addiction

For UCSB researcher Karen Szumlinski, who specializes in the neurobiology of addiction, the opioid epidemic is like a long, slow train wreck. A professor in the campus’s Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, Szumlinski was in graduate school in the 1990s when OxyContin hit the market in a big way, after the decades-long rise in popularity of opioids for pain management.

“I participated in a mock scenario for the medical students and we were doing scenarios on prescription opioid abuse,” Szumlinski recalled. “And then an M.D. came who lost her license because she had gotten hooked.”

Since those early days, opioid abuse has spread throughout the country, driving the skyrocketing rates of drug overdoses and ravaging communities, particularly in the Midwest and Appalachia. So pervasive is the epidemic that the opioid blocker Narcan (naloxone HCI), once available only through doctors or emergency medical personnel, can now be purchased over the counter at drugstores in 46 states.

Inherent challenges of research

Despite the ever-increasing number of deaths and high-profile overdoses — not to mention the babies born addicted as the epidemic reaching a new generation of users — Szumlinski said scientists still understand precious little of the neurobiology of opioid addiction.

And it all comes down to research.

Part of the reason is a lack of adequate funding for studies looking at the different aspects of opioid addiction; but much of it also is because of the complexity surrounding human subjects. It is possible to study treatment-seeking individuals if the researchers are testing the effects of a potential therapeutic, Szumlinski said. However, they may not administer opioids to those people to determine how the potential therapeutic might interact with the effects of the opioid.

“That being said,” she continued, “it is impossible to study the biopsychological underpinnings of how a person transitions from recreational use/abuse to addiction because it is unethical to repeatedly administer an addictive substance to humans.”

Seeking answers in other forms of addiction

Some information regarding important factors that contribute to addiction liability can be gleaned from studies of humans who use other, legal, addictive substances, such as tobacco and alcohol. “In alcoholism, one of the better predictors of abuse vulnerability is family history,” Szumlinski said. “In people with a family history of alcoholism, individuals tend to experience a faster onset of the stimulant properties of alcohol. So, as alcohol is rising in their bloodstream, they start feeling stimulated even before the alcohol level has peaked.

“And then when the alcohol starts to leave the system, less addiction-vulnerable people experience a crash, and then a hangover. However, individuals with a family history of alcoholism tend to experience less crash and hangover,” she continued. “So, these addiction-vulnerable people are experiencing the positive effects of alcohol sooner and experience less of the negative effects later. These types of responses predict whether or not a person may be at risk for developing addiction. And that makes sense. Less well-studied is clinical literature indicating that individual differences in the initial subjective effects of opioids can predict abuse liability.”

Still, with so little usable data on opioid dependency, developing more effective treatments and therapies is a tremendous challenge. Why, for example, do some people respond to some medications but not others in the same family of opioids?

Adding to that is activity-dependent pharmacology, the recently discovered phenomenon in which different antagonists (drugs that block specific receptors) can produce opposite effects on the same receptor, depending on the activity state of the receptor. “The more we’re learning from a basic pharmacology, neuroscience and genetics perspective, the more complicated the scenario is becoming,” Szumlinski said.

The struggle with cravings

Compounding the problem, she added, is our lack of understanding regarding the neurobiology of craving, which is a hallmark feature of addiction that continues even after signs of physical withdrawal have subsided. In particular, the ability of drug-related cues and contexts to elicit craving is now well-characterized to ramp up over time.

“It’s hard to predict when and where that craving will strike, but even months into recovery, a cue — maybe a room where a former user once did drugs, or an activity, or a person — can bring it back in a strong way,” explained Szumlinski. “It’s called the incubation of craving, and it peaks between three to six months into recovery. Unfortunately, the majority of clinical research is conducted on men so it remains to be determined whether a similar sex difference in incubated craving occurs in humans.

“Incubation of craving has been reported in heroin addicts,” she continued. “To date, incubation studies have not yet been published on oxycodone addicts or fentanyl addicts but the fact that craving incubates in cocaine users, methamphetamine users, alcoholics and heroin addicts — it’s highly likely that oxycodone- and fentanyl-addicted people will suffer also from this phenomenon.”

A reason for hope

But Szumlinski sees a bright spot in Vancouver, British Columbia. A network of doctors has been established for addiction treatment in the hopes of outpacing the opioid crisis there, which has come to include analogues such as fentanyl, which is 100 times more potent than morphine, and, more alarmingly, carfentanil, an elephant tranquilizer that is 10,000 times more potent than morphine.

“I’m hoping that if this network initiative works out they’ll write about it in the medical journals so other doctors in the U.S. and Canada can pick up on it and start developing similar types of networks,” Szumlinski said. “Because right now there’s so little addiction-relevant education for medical professionals; doctors are simply not equipped with the knowledge necessary to identify and treat addicted individuals, let alone treat comorbid diseases, such as depression, psychosis or anxiety disorder, interacting with the addiction to affect recovery.”

In addition to the IHC, the Quinones talk is sponsored by UCSB’s Walter H. Capps Center for the Study of Ethics, Religion, and Public Life and by the IHC’s Idee Levitan Endowment.