A Clinician’s Toolkit

Psychotherapists will tell you that one of the most challenging aspects of treating people is the gap between sessions.

“A lot of people think, ‘I’m going to change because I go to a 50-minute session once a week, and magic is going to happen.’ Nonsense,” said Andrés Consoli, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Counseling, Clinical and School Psychology in the Gevirtz Graduate School of Education. “Generally, treatment gains don’t happen only in therapy; they also, if not mostly, happen between what happened that hour and the next hour a week later.”

In an effort to bridge that gap between sessions, Consoli co-authored “CBT Strategies for Anxious and Depressed Children and Adolescents: A Clinician’s Toolkit” (The Guilford Press, 2017). The book, what Consoli called a “shared instrument,” is designed to give patients a way to reinforce their gains when they’re not in session. It does that by providing forms or worksheets children and adolescents can do during session but also on their own at home with their therapist’s guidance.

“The beauty of this is it gives you the chance to look at, first and foremost, generalization of treatment gains,” Consoli explained. “To what extent are gains you did in therapy actually generalized to other places? You’re doing it elsewhere. So the treatment actually extends. It’s not just the usual 50 minutes that we’re together, but you’re actually doing things elsewhere too, which is the goal of therapy.”

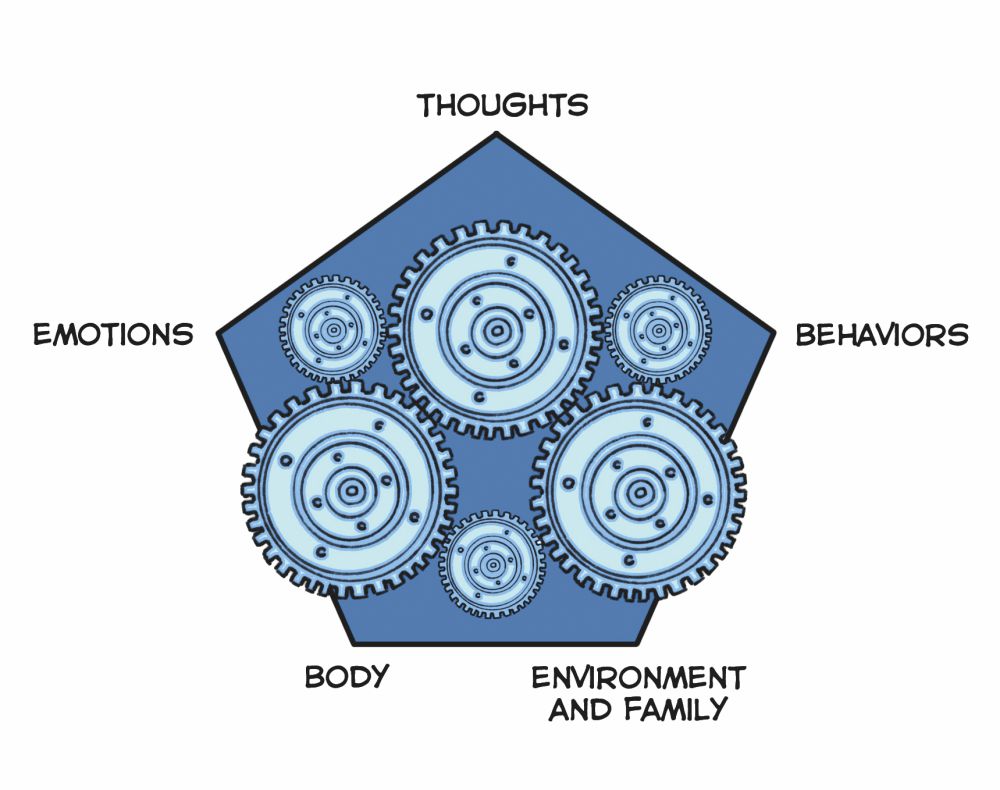

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is based on the idea that the way you think affects the way you behave. Ergo, a change in cognition will prompt a change in behavior. But it’s not that simple, Consoli said. “It’s a half-truth,” he said. “Yes, if I change the way I think I may act differently. But there’s also context.”

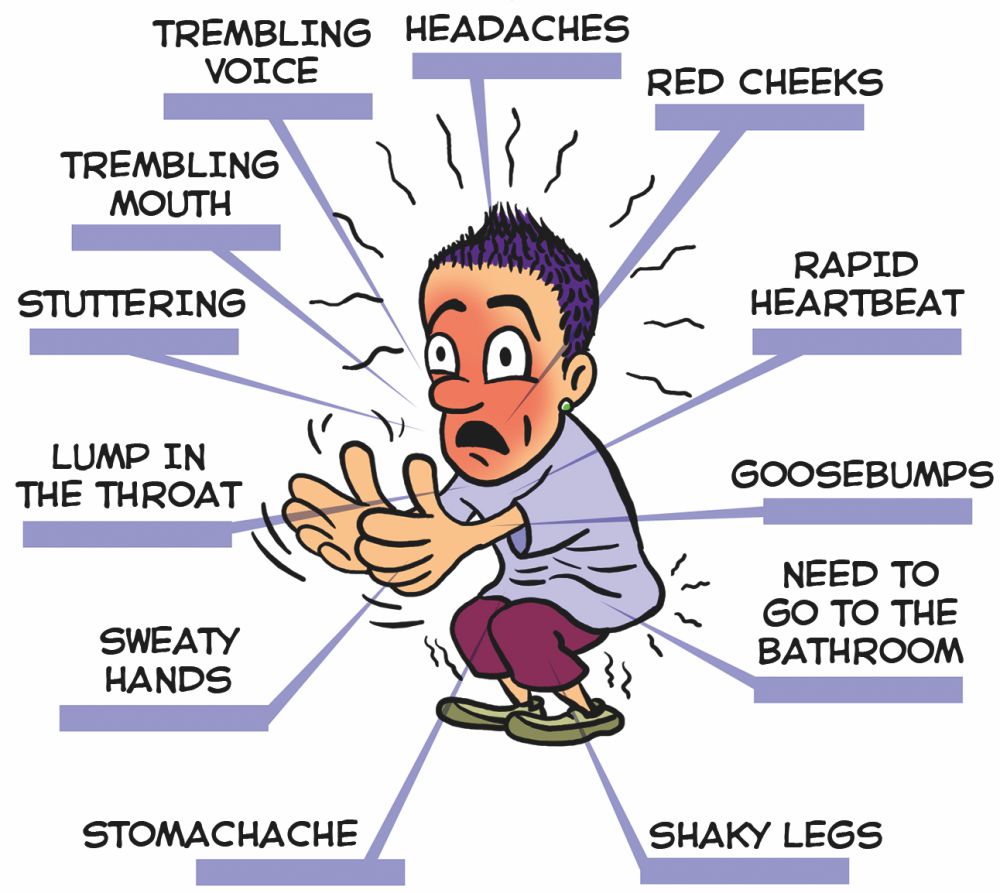

Context — physiological issues that result in social humiliation, family difficulties, racism and more — matters, Consoli noted. CBT as approached in the book, he said, is “constructivistic” and takes into account behaviors, cognitions, emotions, meaning-making and context. In other words, it seeks to expand the way one may think, act or feel about something rather than “correct” it.

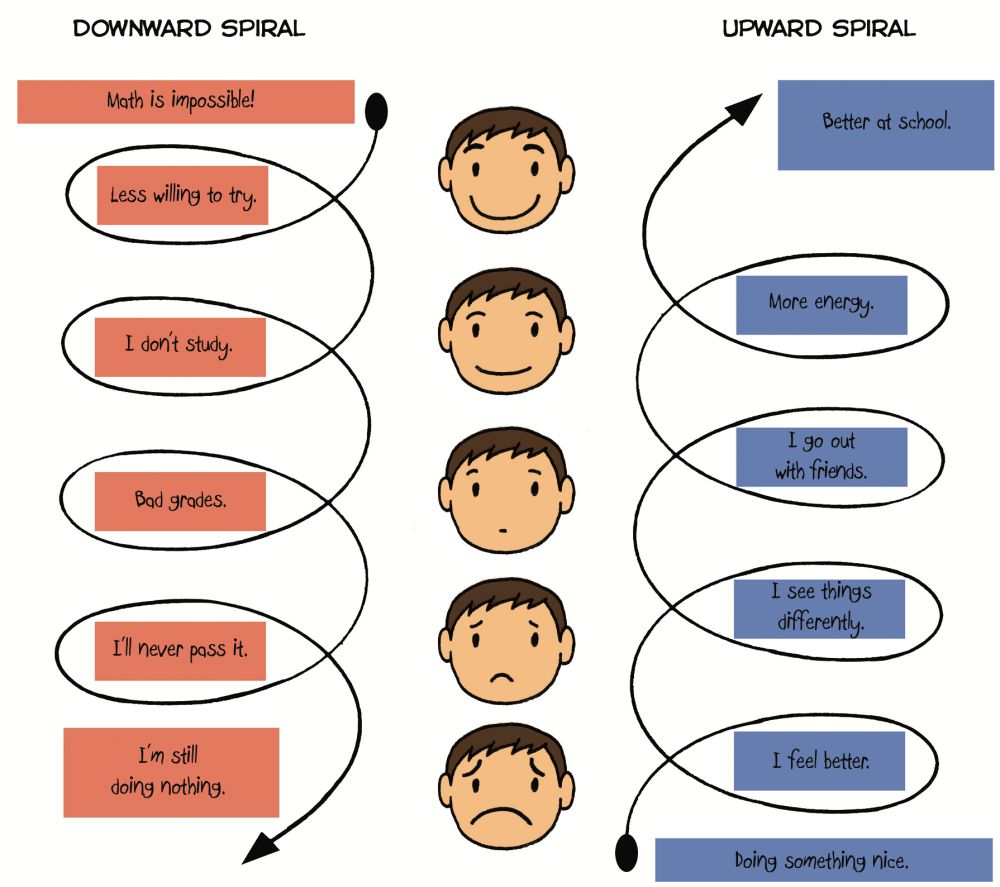

Consider avoidance, which Consoli calls “the most common behavioral problem, especially when it comes to anxiety. The problem with avoidance is it engenders further avoidance. And the outcome of that is we feel less and less competent. It undermines our self-esteem.”

A behavior like avoidance results in a downward spiral, he said. One day, for example, a child might wet his pants in front of the class. To avoid further humiliation he might refuse to speak in class. And then he avoids his friends. Before long he refuses to go to school.

“Avoidance serves it purpose, but when it spreads to that level it begins to undermine what we can do,” Consoli said. “The more we avoid, the more we avoid until it gets to a point where we see people house-bound, confined.”

“CBT Strategies,” which Consoli wrote with Eduardo Bunge of Palo Alto University, and Javier Mandil and Martín Gomar, both psychotherapists in Argentina, includes illustrated worksheets that young patients use to help understand and solve difficulties and maintain the gains they make. The worksheets are easily photocopied. They can also be downloaded and printed.

Because the book is aimed at treating young people, the worksheets are colorfully illustrated with cartoon characters such as Enriqueta and her cat Fellini, done by accomplished cartoonists such as Liniers (Ricardo Siri). It is also, Consoli noted, careful to include people of different races and ethnicities and be gender balanced. “One of the strengths of the book is it is very much culturally sensitive and gender-inclusive,” he said. “We tried to do that systematically throughout the book.”

Consoli stressed that the book is an adjunct to therapy, one that gives clinicians a way to keep their patients progressing away from sessions. “You have a lot of tools there,” he said. “You can use them as you see fit. But it’s really about engagement. It’s not about taking clinicians’ minds out of it. It’s really to bring your mind and your creativity into it. You can’t just hit the kid on the head with the book and say, ‘It’s going to be done.’ It doesn’t work that way.”

In addition to “CBT Strategies,” Consoli is also the lead editor of “Comprehensive Textbook of Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice” (Oxford University Press, 2017). A second edition, he described it as “a completely different book,” with 75 authors, 80 to 90 percent of whom are new.