They Persisted

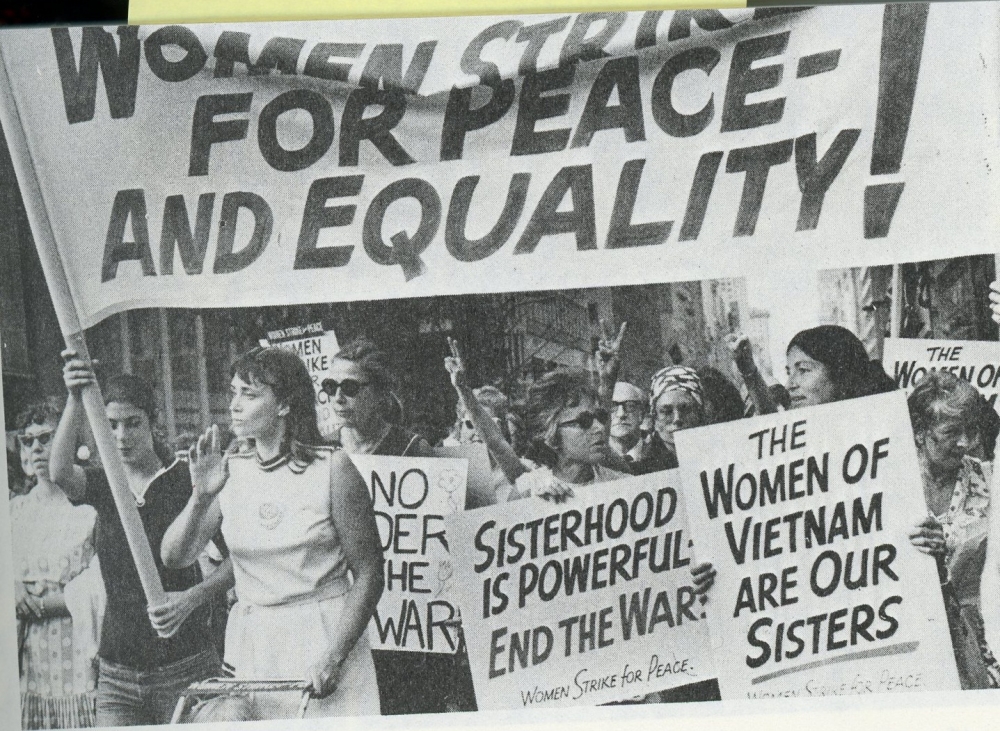

It is estimated that more than 5 million people worldwide participated in marches on Jan. 21, gathering together to show support for women’s rights, reproductive rights, gender and racial equality and many other interconnected causes.

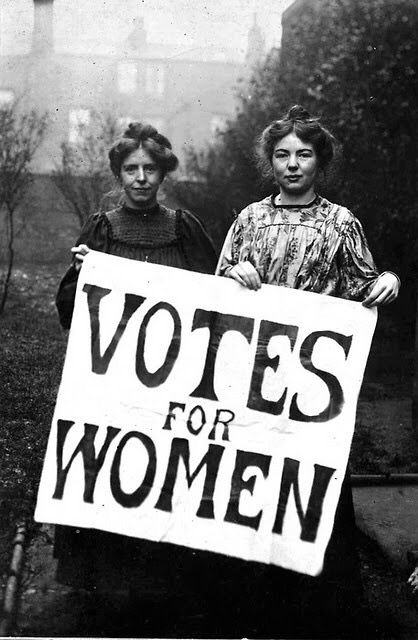

But how did a march that started as a simple Facebook post, created by a group of women who planned to protest the outcome of the recent presidential election, garner so much attention? What are the implications of the historic gathering, and in what ways is it a continuation of the suffrage movement — which sought to give women the right to vote in the first place — and the women’s movement of the 1970s?

In some ways, the 2017 march was not so different from meetings to discuss women’s right in the 1840s. In other ways, it was a quintessentially 21st century phenomenon. How and why it succeeded speaks both to the long history of movements that preceded it and to this exact moment in time.

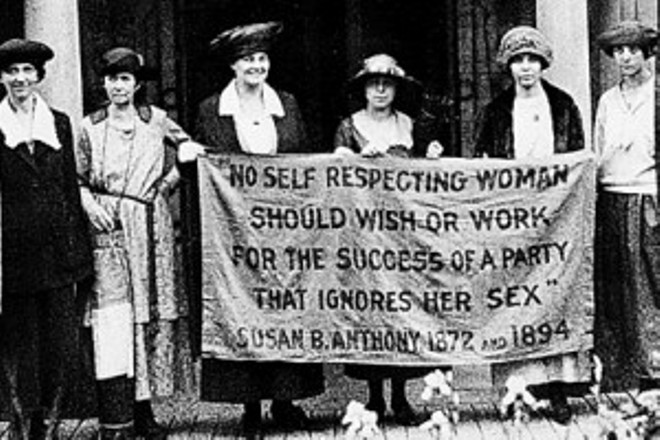

“Research on social movements and women’s activism helps us to understand how change occurred in the past and provides signposts for how to make change happen in the present and future,” said Leila Rupp, interim dean of social sciences in UCSB’s College of Letters and Science and a professor of feminist studies. “The suffrage movement, the civil rights movement, the anti-rape movement, the reproductive justice movement, to name a few, mobilized women — and men — and made a difference.”

Mobilizing Millions

The mission of the Women’s March on Washington, in the language of its founders, was “to send a bold message to our new government on their first day in office, and to the world that women’s rights are human rights.” One major deviation from earlier movements, however, was how that message was relayed: by way of a website.

“The nationwide nature of the protest was undoubtedly the result of the preexisting organizational, network and internet ties of the participants,” said Verta Taylor, a professor of sociology and of feminist studies. “This is in sharp contrast to the early days of the suffrage campaign, when activists had to rely primarily on print media and letter writing to mobilize participants.” Activism, she added, has always been community-based, but the size and shape of the community has shifted with the advent of web-based social networks.

Taylor is the author of the forthcoming book, “The Oxford Handbook of Women’s Social Movement Activism,” the largest collection of original essays on U.S. women’s social movement activism to date. In the book, she and her co-authors present the words and stories of women who have participated in activism throughout history.

“Participating in protest, demonstrations and other forms of activism is one of the major ways that women forge solidarity, raise their gender consciousness and create a feminist collective identity,” explained Taylor. “The issues that are leading women to become social movement activists today are remarkably similar to those that sparked protest by suffragists and so-called second- and third-wave feminists — gender inequality in all spheres of life, from intimate relations to the workplace to politics.”

Zakiya Luna, an assistant professor in the department of sociology, pointed out that online activism didn’t stop with organization of the Jan. 21 marches. “Social media was incorporated in different ways at the marches, too,” she said. “For example, the D.C. march had an app with a schedule and forums for sharing information.”

Luna is currently a principal investigator on a project called “Mobilizing Millions — Engendering Protest Across the Globe.” The project aims to survey those who chose to march as well as those who chose not to participate in order to understand the complex framework of identity, discourse, politics and other factors that affected participation. So far, they have received more than 3000 responses from around the world.

“Our preliminary findings from the observations and survey highlight that one, there were a range of reasons people attended marches and two, across and within sites, there were varying experiences of ‘the’ march in any location,” Luna commented. “This makes sense when you consider that in many locations, the number of attendees exceeded projections.”

All Are Welcome

Taylor emphasized that while publicity methods may change, the themes that inspire women to mobilize for social causes remain the same, if perhaps more inclusive. “A big difference that I observed during the most recent women’s marches was activists’ embrace of racial, class and gender inclusivity, which contributed to the mobilization of a more diverse set of participants,” she commented. “For example, men were more likely to participate in these marches than in many of the early women’s movement demonstrations, and there was considerable racial and ethnic diversity among protestors.”

Sarah Case, a lecturer in the UCSB Department of History who teaches a course titled “Women in American History,” sees the effort to maintain a broad activist base as a possible hindrance to Trump-era women’s movements. “Right now, this movement seems to be against something — the president — but is still in some ways searching for what it is for,” she said. “This is in contrast to single-issue movements in the past, like suffrage. In a way, this is good because it is inclusive, but it will be hard to come up with a proactive (rather than reactive) agenda.”

For Taylor, recent marches have demonstrated the intersectional nature of modern social activism. “The Women’s March on Washington illustrates how the ideas, tactics, participants and organizations of one movement tend to spill over its boundaries to affect other movements,” she said, “Feminism spilled over to other recent social movements, including Occupy Wall Street, the immigrant rights movement, Black Lives Matter, and environmental movements, and these networks of activists were mobilized to participate in the Women’s March through their existing organizational networks and internet ties.”

Timing is Everything

Also critical to the success of any social movement is the element of timing. Taylor described these “cycles of heightened mobilization” as being tied to big, often polarizing events. “Prior research suggests that women’s movements have been more successful in achieving their goals when the political system is open and political elites are receptive to their claims,” said Taylor. However, she noted, social movement scholars also recognize that threats are often as likely as political opportunities to mobilize activists, because threats create feelings of moral outrage and urgency.

“My best prediction is that we will see a resurgence of feminist protest during the Trump era because of three factors,” Taylor continued. “One, the increase in threat; two, the existence of a behemoth of feminist and women’s organizations; and three, the growing coalitions that are forming among progressive groups focused on issues such as the environment, reproductive rights, racism in policing, LGBTQ rights and Muslim rights.”

Or, it could just be a case of finding the right way to market the cause to attract the greatest possible number of supporters. “The suffrage movement ‘officially’ began at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848, but most women did not support suffrage until into the 20th century,” Case explained. “It became a mass movement only after the major suffrage organization shifted its rationale for voting from ‘equal rights’ to ‘women’s duty’ — that is, women as mothers had a special responsibility to vote to improve and uplift society.”

The Road Ahead

Case recognized that activist movements often inspire counter-movements on the opposite side of an issue. “Since the 1970s, women’s historians have had to acknowledge the fact that conservative women’s activism has been at least as powerful and significant as feminism,” she said, pointing to the anti-suffrage movement that morphed into a reactionary anti-immigrant movement.

Just don’t call the recent marches and increased activism a wave. Scholars of social movements often reject the idea of “waves” of activism because it dismisses the steady, persistent work that must come before and after a peak in activity.

“The wave metaphor focuses on state-centered national mobilizations and, when these are not evident, the women’s movement is considered to be in decline. As a result, a considerable amount of women’s activism and its impact on social change gets overlooked,” explained Taylor. “A more continuous approach that recognizes persistence over time allows us to understand the ‘carry-overs and carry-ons’ between different cycles of mobilization.”

No matter what a surge of activism is called, Luna’s research shows that many modern activists are uninterested in labeling their participation at all, even though it might fit a formal definition.

“What I think is most important is understanding what matters enough to people to get them involved in protest and formal politics, despite the many barriers to doing so,” she explained, citing the stigma associated with activism and busy schedules as possible reasons not to participate. “Based on what people posted on social media before the 2017 Women’s March, there is evidence that many participants did not identify as activists or feminists. Yet, on January 21, 2017, millions marched throughout the world.”

Despite possible setbacks, Taylor doesn’t see the present-day women’s movement slowing down any time soon. “Contemporary women activists draw on the commitment and history of earlier feminist activists — their ideas, their tactics and strategies and lessons learned in the past — to form solidarity and make decisions about plausible goals and tactics in the present,” she said. “And their activism, in turn, shapes future cycles of feminist activism.”