A Fateful Decade

While the United States has a visibly fraught relationship with Arabs and much of the Middle East, how it got that way is a complex story filled with geopolitical intrigue. A new book by a UC Santa Barbara scholar takes a close and revealing look at the pivotal decade that shaped the American experience in the Mideast.

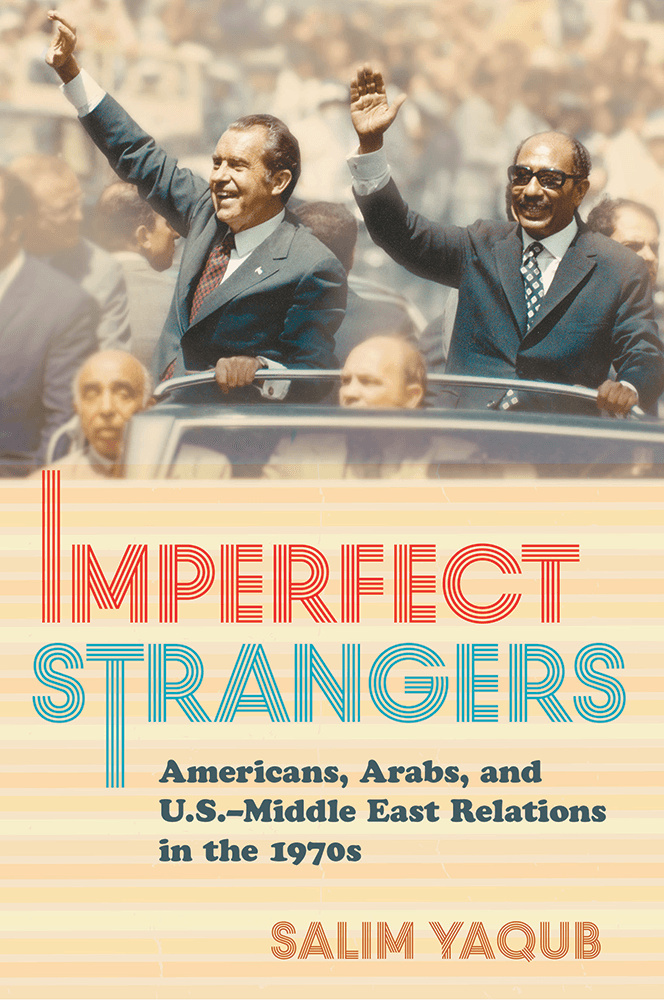

“Imperfect Strangers: Americans, Arabs and U.S.-Middle East Relations in the 1970s” (Cornell University Press, 2016) by Salim Yaqub, a professor of history at UCSB, examines how the U.S. found itself entangled in the region and the rise of Arab-American activism and influence. “A perfect stranger is someone you don’t know at all,” he said. “I’m arguing in the book that the two societies came to know each other better during the ’70s. So they were not perfect strangers anymore, but imperfect strangers. Also imperfect in the sense that they are flawed human beings.”

Yaqub writes largely through the prism of the Arab-Israeli conflict, especially from the 1967 Six-Day War on. He argues that the conflict drove nearly all Middle East-related events, political and military, of the era. Indeed, he sees America’s most lasting diplomatic contribution, the Camp David Accords of 1978, as a significant barrier to a larger, permanent resolution of the conflict.

Yaqub writes that the bilateral peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, though consummated during the presidency of Jimmy Carter, grew out of the Machiavellian diplomacy of a previous secretary of state, Henry Kissinger. The treaty, he argues, accomplished at least two things. To start, removing Egypt from the alliance of Arab actors that opposed Israel weakened the alliance and strengthened Israel. Then, it allowed Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to pivot from the Soviet Union to the U.S., giving the Americans a bigger footprint — and more influence — in the region. “[Kissinger] isn’t trying to resolve the conflict; he’s trying to manage it,” Yaqub said.

“Kissinger’s basic view, I think, was that the overall Arab-Israeli conflict was not something that could be resolved anytime soon, probably not in his lifetime,” Yaqub explained. “What he wanted to do instead was make the situation of Israel more secure in his view. He wanted to shield Israel from international pressure to conduct a full-scale withdrawal from all the territories it has occupied in the 1967 war. He basically agreed with the Israeli view that the borders Israel had prior to the ’67 war were indefensible, and Israeli security required some wider territory under Israeli government control.”

The ’70s were also a time when Arab Americans rose to become influential activists and intellectuals, Yaqub said. Although people of Arab descent had been in the U.S. since the late 19th century, they were overwhelmingly Christian, and identified as Lebanese or Syrian American. But the end of the U.S. immigration quota system in the mid-1960s, which had favored western and northern Europeans, allowed Muslim Arabs from around the world to emigrate to America. “Arab American political activism really takes off after ’67, and becomes more and more prominent into the 1970s,” Yaqub noted.

The Arab oil embargo of the ’70s forced the American public to pay attention to the politics of Mideast and their consequences for U.S. consumers. And that, Yaqub said, gave Arab Americans the opportunity to talk about the issues. With the embargo, he said, “Suddenly millions of Americans are saying, ‘Hey, how come I can’t buy gas? What’s this all about?’ Arab Americans are able to say, ‘Aha! Yes, I’m glad you asked that question. Here’s my take on it.’ ”

For Arab Americans, the ’70s were also period of fluid identity, Yaqub said. Before the end of the ’60s, he explained, the dominant Christian Arabs were generally regarded as “white ethnics” — similar to other immigrants of Mediterranean or even southern European background — and largely assimilated into U.S. culture. Some of the later immigrants, however, were visibly less assimilated and seen as outsiders and not American. Yaqub grants there was deassimilation among some Arab Americans in the ’70s, but argues that it was also a period when “they became more sophisticated and experienced in navigating various elements of American political society — lobbying Congress, communicating with the media, establishing pockets of influence in various elements of the intelligentsia, especially academia.”