Dispatch From Fire Island

It was one of the first hurricanes of the season, and among the most deadly. Striking off the eastern seaboard on July 19, 1850, it brought gale-force winds and huge waves that pummeled the Elizabeth, a 530-ton vessel that had set sail from Leghorn, Italy, two months earlier.

On board were five passengers, including the American journalist and author Margaret Fuller, her husband, Count Giovanni Ossoli, and their son, Angelino, as well as a crew of 14. The cargo hold carried 100 tons of rough-hewn marble, a statue of former Vice President John C. Calhoun and various and sundry items.

In the early morning hours, a giant wave upheaved the ship and slammed it into a sand bar just off Fire Island, sending chunks of loose marble flying through the side of the vessel. The hold flooded, the ship was destroyed and Fuller, Ossoli and 2-year-old Angelino drowned.

Fuller’s death sent shockwaves through the country’s literary community. A contemporary of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, Fuller — a noted feminist associated with the American transcendentalism movement — had traveled to Italy as a foreign correspondent for Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune to cover the Italian revolution.

Six days after the tragedy, Emerson deputized Thoreau to travel from Concord, Massachusetts, to the site of the shipwreck and gather any remains or property he could find of Fuller and her family. “Of particular interest,” said Elizabeth Witherell, a Thoreau scholar at UC Santa Barbara, “was a history of the mid-century revolutions in Italy, which Fuller had completed and was bringing back for publication.”

No portion of the manuscript was recovered.

When Thoreau returned to Concord in late July or early August, he met with Emerson. Reading from his extensive notes, he reported what he had learned.

Fast-Forward: Bringing History to Life

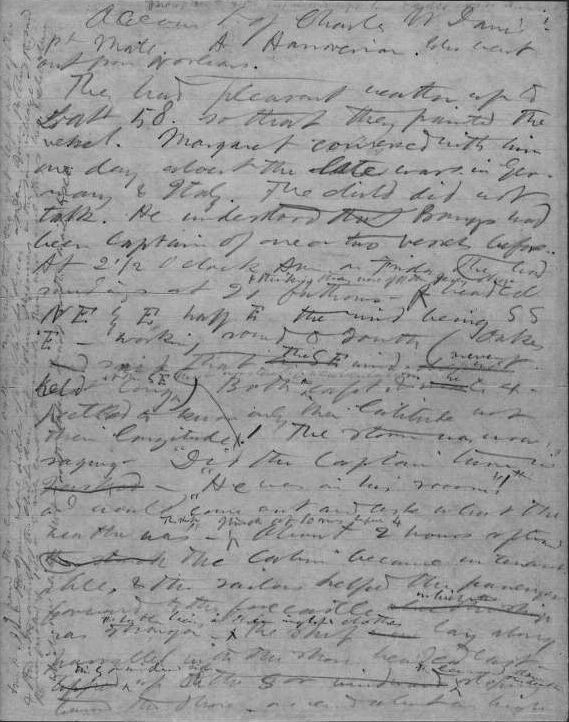

Last spring, the Houghton Library at Harvard University acquired an 18-page manuscript consisting of the penciled first draft of those notes, and in the spirit of scholarly collaboration, Witherell offered to transcribe it.

Witherell is editor-in-chief of “The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau,” a projected 28-volume scholarly endeavor based at the UCSB Library. When completed, the Thoreau Edition, as it’s known, will include the contents of each of the 47 manuscript volumes of the 19th-century American naturalist and social philosopher’s handwritten journal, his writings for publication, his correspondence and other uncollected papers.

The Fire Island manuscript will be included in an annotation in “Correspondence 2: 1849-1856,” the Thoreau Edition’s second volume of letters by and to Thoreau, forthcoming in 2017.

“Beth Witherell had been extraordinarily helpful when we were researching the provenance of the manuscript,” said Leslie Morris, curator of modern books and manuscripts at Houghton. “Given how difficult Thoreau’s rough notes were to read, I was grateful to have an expert scholar take on that difficult task of transcribing them. And of course we were eager to have them included as part of the standard scholarly edition.”

“I’ve transcribed hundreds of pages of Thoreau’s handwriting, but I’ve very rarely been the first to work on a completely new manuscript,” said Witherell. “It was beyond exciting to have a chance to do that.

“I knew the manuscript would be a major addition to the Houghton’s collection because there’s no full account by Thoreau of what his investigation on Fire Island involved,” she added. “And there are so few extensive Thoreau manuscripts coming on the market anymore that this is a really big deal.”

So big, in fact, that Witherell arranged with the publisher, Princeton University Press, to hold up production of “Correspondence 2,” originally set for publication in 2016, so the contents of the manuscript could be added. “It fits into our volume as an annotation for Thoreau’s letter to Emerson discussing his efforts on Fire Island,” she explained. “There are three or four letters in which the Fire Island trip is mentioned, which makes the manuscript uniquely relevant to this period of time.”

Transcribing the nine-page manuscript was an intense job for Witherell, but a labor of infinite love. “I couldn’t stop working on it,” she said. “It was such a thrilling story, and so poignant. There’s a description of the little boy’s body being carried up to the wreckers’ house.” Wreckers, in this case a Mr. and Mrs. Oakes, are those whose profession it was to gather up whatever stuff — personal and otherwise — washed up on shore following a shipwreck.

Deciphering the Words

“It was heavy going for transcription because it’s in pencil and things are crossed out,” Witherell continued. “Sometimes when I have had a draft of something by Thoreau I’ve also had the finished product and I could go back and forth. But this required me to be creative; sometimes I could use a couple of legible characters to work out a whole word. Several times as I stared at a series of undifferentiated bumps, a word gradually emerged, almost as though the manuscript were communicating with me.”

To aid in her work, she read accounts of the event in various historical and scholarly books and publications. She also consulted local newspapers — the Long-Islander, among others — and studied their accounts. “That gave me a lot of background about the cargo, for example,” she said. “There’s one passage about the marble breaking the knees: ‘The marble caused that at the first thump she broke her knees off like pipe staves,’” Witherell noted. “Ships have knees — I knew that from something else Thoreau had written. They are the curved pieces that hold the hull in shape. So things like that helped me look at words that I was not at all sure of and figure out what they probably were.”

According to Witherell, Thoreau interviewed several people who were involved in the incident, including crewmembers who had survived — the first mate and the carpenter — as well as the wreckers. “One of the reasons Fuller and her husband and child died was that the wreckers refused to take the lifeboat out,” she said.

“The lifeboat was brought from the lighthouse, but it was never taken out to rescue the people on the boat because the wreckers, apparently, were not going to put themselves in danger. And they were waiting for the stuff that came ashore.

“That part of the story is just excruciating,” Witherell continued. “The boat was right offshore, only about 300 yards away. The people who did make it to shore used planks from the ship to support themselves.”

Journalistic Integrity

Among the many facets of the manuscript that fascinated Witherell as she completed the transcription was the journalistic distance Thoreau maintained as he interviewed people. “He doesn’t judge; he works to shape the account to what they said to him,” she said. “He doesn’t react in the account he gives of his interviews. But when he gets to the wreckers, in the unedited transcript, he says some pretty sharp things.”

Witherell added that this previously unpublished manuscript, the longest and most interesting she’s seen on the market in more than 20 years, is important to Thoreau scholars because it documents his deep involvement in the mission in greater detail than he includes in his letters. It is likewise important to Fuller scholars because it contains information about the wreck not previously available.

“This is Thoreau’s account of an event that resonated in the intellectual community of the United States because Margaret Fuller was the most important woman writer of her time,” said Witherell. “So this is part both of Thoreau’s biography and of the important events of the transcendental period.”

The edited transcription as well as images of the original manuscript pages are available on The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau website.