Gateway to Freedom

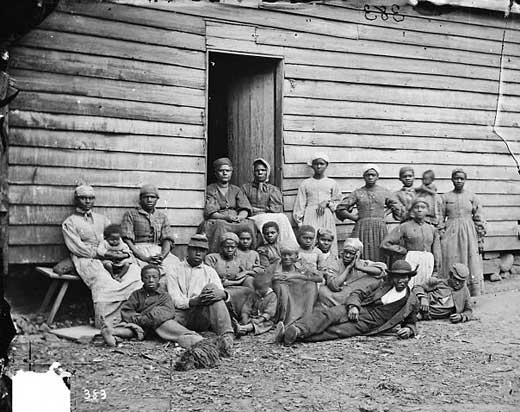

Between 1830 and 1860 more than 3,000 fugitive slaves made their way from the southern United States — where slavery was an accepted institution — to states in the north and to Canada, where they could live as free men and women.

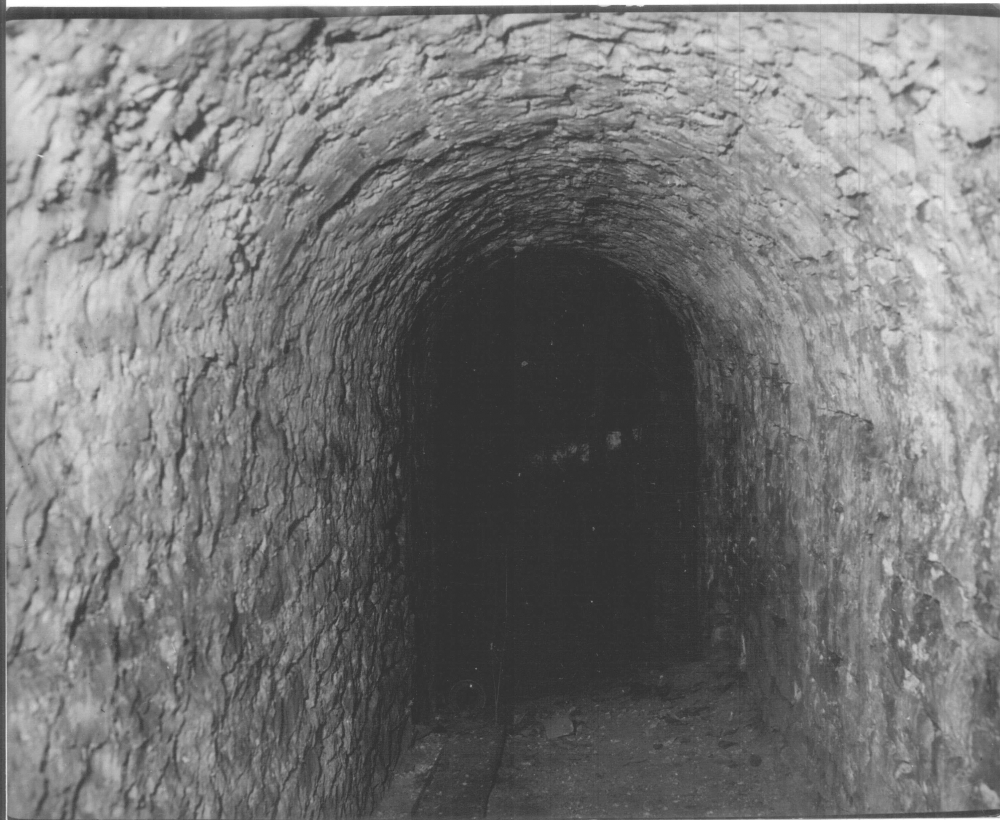

The journey was long and harrowing, and the travelers were helped along the way by networks of antislavery resistance. These networks provided secret routes, passageways, meeting places and safe houses, and together they became known as the Underground Railroad.

In keeping with that metaphor, the homes and businesses that harbored runaway slaves were referred to as “stations” or “depots” and they were operated by “stationmasters.” “Conductors” — such as the well-known and highly revered Harriet Tubman — helped the fugitives move from one station to the next and “stockholders” provided money or goods such as food and clothing.

Forced to operate in complete secrecy — and therefore leaving very little in the way of historical documents — the Underground Railroad has proved enigmatic to historians, and its stories have remained largely unknown.

Until now.

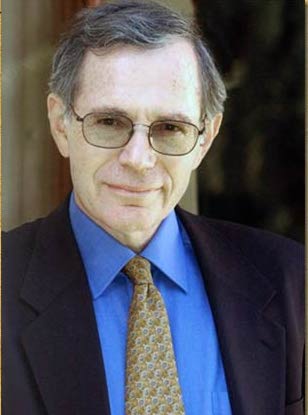

Speaking Tuesday, March 3, at UC Santa Barbara’s Capps Forum on Ethics and Public Policy, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and author Eric Foner will explore the story of the Underground Railroad, building on new evidence that includes a detailed record kept by Sydney Howard Gay, one of the key organizers in New York.

Foner’s talk focuses on his latest book, “Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad.” It will begin at 5 p.m in UCSB’s Campbell Hall. It is free and open to the public.

“I think the significance of Foner’s talk is his trying to carve out an argument about how widespread the Underground Railroad was,” said Terence Keel, assistant professor at UCSB, jointly appointed in the Black Studies and history departments. “But more than that, the Underground Railroad was a coalitional political project that involved African Americans who had run away, as well as white abolitionists and Quakers who were actively working together to create this network of support.”

According to Keel, Foner’s talk will assist students in understanding the relevance of a history from which many of them feel far removed. “There’s an assumption that what happened 150 years ago really doesn’t have any bearing on their lives today,” Keel said. “And I think that’s unfortunate because the Underground Railroad is a story about black and white solidarity in the struggle for freedom and justice, and this is a consistent feature of African American history and American history in general.”

Keel is currently teaching an introductory course on black studies and his student body is predominantly white. In framing the course, he points out that African American history does not exclude non-African Americans. Their history, he notes, is a history of the American people. “It’s a history of black agency and partnership with other people,” he said. “Yet often students assume that a course on African American history is about demarcating boundaries and defining who is and who isn’t a proper part of this history.”

Keel added that he hopes Foner’s attention to abolitionists Thomas Garrett and Sydney Howard Gay, who worked with Tubman, will help students understand this history as involving both blacks and whites. “Students can narrate themselves into a history they otherwise don’t see themselves a part of,” he said.

Equally important in Foner’s talk — and in his book — according to Keel, is Foner’s attempt to dispel the myth that insufficient archival resources are available to demonstrate fully how widespread and systematically the Underground Railroad operated. “This is a kind of perennial problem in African American history,” Keel noted. “In part it’s because the Underground Railroad was a clandestine operation. Its success depended on secrecy.

“This is not one of those research sites where there’s a robust archive,” Keel went on. “But it so happens Foner did in fact stumble across the record book in which Sydney Howard Gay was cataloging the number of slaves who were making their way up north. It was a record of the names of the slaves and potentially where they were from. And now we can begin to put names to regions and frequencies and time periods in ways that historically haven’t been possible. And that’s ground-breaking.”

Keel noted that one of the most important back-stories to the Underground Railroad is the Fugitive Slave Act that was passed in 1850. Prior to 1850, northern states established laws that essentially freed officials there from helping southerners reclaim slaves who had escaped to the north. The Fugitive Slave Act, however, required northerners to help slave catchers return slaves to the south.

“The north was up in arms about this,” said Keel. “In their minds, this was federal law encroaching upon state law. And also, more than anything else, it implicated them in the institution of slavery that they increasingly wanted nothing to do with. The moral indignation and outrage northern whites had toward this law, which then foments more support for the Underground Railroad, is one of the clearest examples of how many northern whites had become fed up with the institution of slavery and found it to be inhumane and in violation of basic human rights.”

Archival moments, such as those depicted in Foner’s book, are hugely valuable to every historian of the period, Keel noted. “They tell us that history is never static,” he said. “It’s always being remade and reshaped. And I think one of the responsibilities historians have to the present is to continue to look for sources that reshape how we think about the past.”

The DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, Foner specializes in the Civil War and Reconstruction, slavery and 19th-century U.S. history. In 2011, his book “The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery” won the Pulitzer Prize in History, the Bancroft Prize and the Lincoln Prize.

Foner’s talk is presented by the UCSB Walter H. Capps Center for the Study of Ethics, Religion, and Public Life and Department of History. It is cosponsored by UCSB’s Center for Black Studies Research, Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy, Department of Black Studies, Global & International Studies Program, Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, and the UC Center for New Racial Studies.