Exporting Hollywood

It has all the makings of an action thriller straight out of a Hollywood studio. In reality, though, the story is Hollywood itself and its aggressive strategy for operating movie theaters around the world from 1925 to 2013.

With a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, UC Santa Barbara film historian Ross Melnick is exploring the sprawling history of American studios not only exporting American movies but also building, buying and operating theaters in more than two dozen countries throughout Asia, Africa, South America, the Middle East, Australasia and Europe.

In his book project “Screening the World: Hollywood’s Global Exhibition Empires,” the assistant professor of film and media studies examines the strategy that, while proving a financial success for the studios, also generated considerable controversy, charges of cultural imperialism and occasional violence.

Melnick’s current work follows — and was partly inspired by — his previous book, “American Showman: Samuel ‘Roxy’ Rothafel and the Birth of the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1935” (Columbia University Press, 2012). The origins of his current project date to 2003, when Melnick was conducting research on Rothafel, one of NBC’s earliest radio stars and the impresario of numerous movie palaces, including New York’s eponymous Roxy Theatre and Radio City Music Hall. “I discovered that some of the people he was working with and who were working for him were traveling back and forth to Paris, and I couldn’t figure out why they were going there or who was sending them,” Melnick said.

As he dug deeper, Melnick uncovered a deal between Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios’s parent company, Loew’s, Inc., and the Gaumont Film Company in France that enabled Loew’s/MGM to operate all of the company’s distribution and exhibition operations in France and its numerous colonial outposts, such as Syria and Tunisia. “That led to a full-scale investigation of how prominent this was and how long it went on,” Melnick explained. “Through research conducted over the last dozen years, I’ve discovered that U.S. operation of foreign cinemas was once an important mode of industrial expansion for Hollywood and one that only accelerated after the breakup of the vertically integrated U.S. film industry in the 1940s and 1950s.”

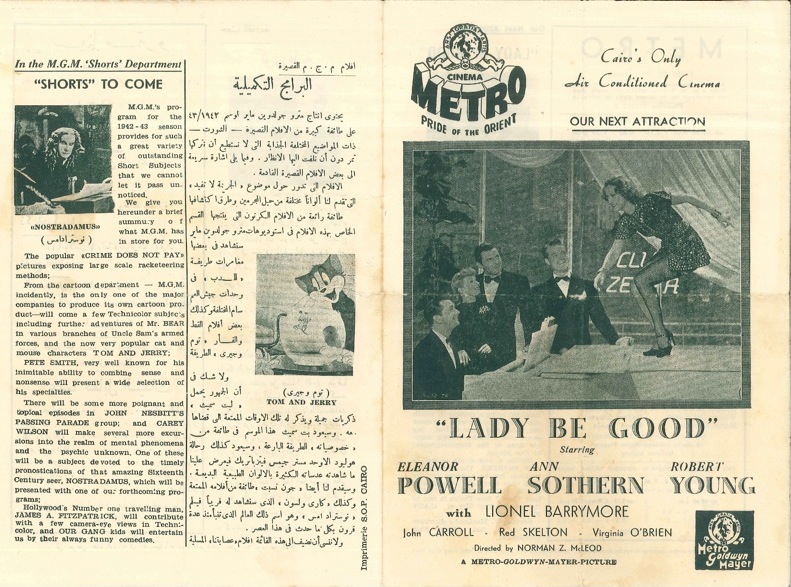

However, tracing each studio’s operations and the cultural, industrial and political impact of that expansion didn’t follow one particular pattern, according to Melnick. “Every country presented a different challenge and opportunity, and every corporation operated differently,” he said. “There are significant reasons, for instance, why MGM and Fox opened cinemas in Egypt in the 1940s and in Israel in the 1950s, and why the company expanded its operations in South Africa but not in Nigeria.”

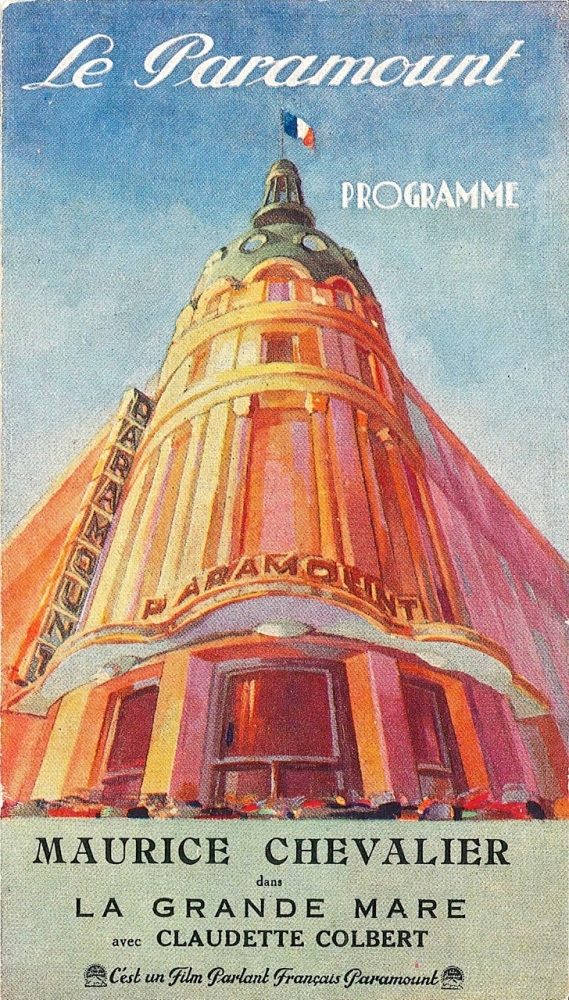

Given the scale of these enterprises, Melnick uses a series of cases studies — some of which will appear in forthcoming articles in Cinema Journal and Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television — to understand various facets of this global campaign: MGM’s expansion throughout Latin America; Fox’s dramatic takeover of exhibition and distribution in sub-Saharan Africa; Paramount’s complex European operations before and during World War II; and Warner Bros.’ efforts to expand into Cuba before the Revolution and into China during the 21st century.

The studios’ global operations certainly produced their share of political intrigue and social unrest, Melnick noted. In one case, the apartheid government of South Africa warned MGM in 1952 that if it turned a book with interracial themes into a movie, the studio would never be able to release another film in the country. “There were a number of films that didn’t make it to a variety of markets for any number of political or cultural reasons,” he said.

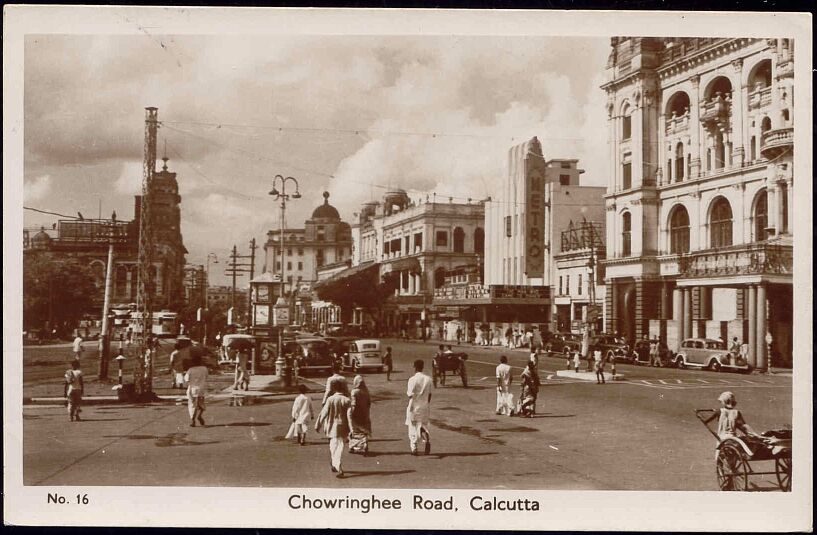

The theaters themselves were often just as controversial. They were designed to be what Melnick calls a “cultural embassy” that enabled local moviegoers “to step onto Hollywood soil.” “Many were modeled on existing U.S. cinemas and had the same architectural styles, interior aesthetics and air conditioning as the company’s U.S. movie theaters,” he explained. “Opulent lobbies featuring uniformed ushers and doormen as well as promotional material for forthcoming Hollywood films sold American movies using a quintessentially American moviegoing experience.”

However, Melnick pointed out, this very American patina also caused them to be highly symbolic targets of industrial, political and cultural resistance, leading to economic boycotts against Paramount cinemas in England in the 1920s, physical attacks on Fox and MGM-owned cinemas in Egypt in the 1940s and 1950s and racial protests against segregated cinemas in Colonial Zimbabwe in the 1950s and 1960s.

For some studio executives, global expansion was also an opportunity to spread American values during the Cold War. “This excitement was matched by the U.S. State Department, which noted that these cinemas could help secure additional venues abroad for U.S. films as well as newsreels that could expand the ideological battle against Communism in contested regions around the world,” Melnick explained.

He added that the ongoing 12-year project has been an invaluable endeavor for his research and teaching. “I’ve had tremendous opportunities to conduct extensive research overseas in countries like Brazil and Italy,” Melnick said. “And each new market has led to invaluable discoveries about the local film industry — and Hollywood operations abroad — that I can share with my students and that will undoubtedly lead to additional research projects in the years to come.”