Scholars of Distinction

In archaeology, the little things matter. Kaitlin Brown noticed changes in Chumash soapstone cooking wares. Mallory Melton found that Native Americans in the Southeast were increasing their collection of foraged resources and decentralizing their maize fields. In each case the graduate students of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara upended traditional thinking about the ways certain indigenous peoples responded to the presence of colonizers and to the dangers unleashed by colonial disruption.

Their findings are detailed in separate papers in the distinguished journal American Antiquity. In “Crafting Identity: Acquisition, Production, Use, and Recycling of Soapstone During the Mission Period in Alta California,” Brown argues that the changing shapes of Chumash cooking wares are evidence of shifting indigenous identities during the Mission Period in what is today the Central Coast of California.

In “Cropping in an Age of Captive Taking: Exploring Evidence for Uncertainty and Food Insecurity in the Seventeenth-Century North Carolina Piedmont,” Melton makes the case that Native Americans during the colonial period adjusted their foodways to cope with the threat of slave raiding that took untold numbers of women and children.

Brown and Melton are members of the Social Archaeology Research Group headed by Gregory H. Wilson, a UCSB associate professor of anthropology. Melton is also a member of the Integrative Subsistence Laboratory, directed by Amber VanDerwarker, a UCSB professor of anthropology.

Entanglement in the Missions

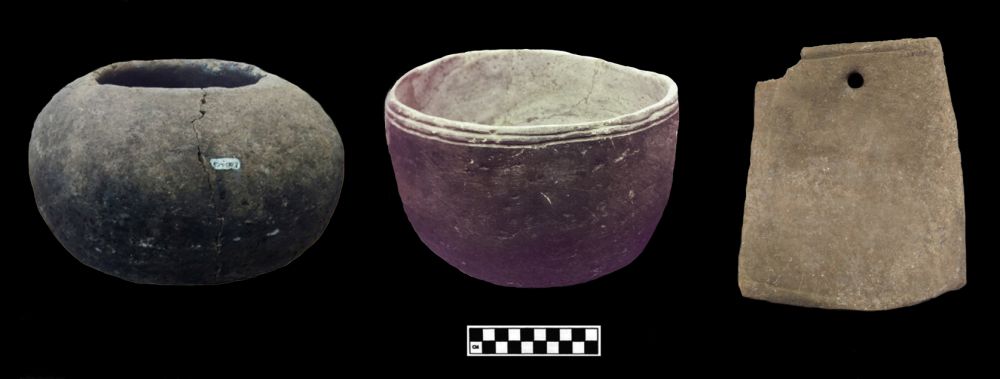

Brown, who has been researching Chumash lifeways in the Mission Period since her undergraduate days at UC San Diego, noted that the use of soapstone was ubiquitous in the Santa Barbara Channel region. For cooking wares, they primarily carved ollas, round pots with narrow openings, and comales, flat griddles.

“There’s just tons of soapstone everywhere,” said Brown, who examined assemblages in museums and missions. “No one’s really done a thorough analysis of this, and the soapstone I was looking at had all of this food residue on it, and it had all this cooking grease. I was trying to understand the chaos of these assemblages and bring some organization to it.”

Eventually, by analyzing changes in the wares over time and geography, she found that soapstone production in the missions shifted. Instead of ollas, Chumash artisans began making Spanish-style bowls and greatly increased the number of comales.

“So what this really shows is the shift towards the incorporation of certain Spanish foodways,” Brown explained. “They’re eating more corn tortillas or wheat tortillas or some type of solid food item with the griddle inside the mission. And they’re cooking their food differently. With ollas you could simmer food and boil foods in them because of their orifices. But bowls, they facilitate the removal of food, and they’re not really used so much for storage. And they’re simmering for longer periods of time rather than long-term boiling.

“It’s a whole shift in foodways happening inside the mission,” she continued, “and what I argue is that this change represents the emergence of new social strategies and social identities among the Chumash people living in the missions.”

That shift in identity, Brown said, is an example of what’s known as “entanglement,” the process by which colonizing powers and indigenous people influence one another and change over time. Outside of the missions there was less change in traditional Chumash cooking wares.

“You find the same number of ollas; you really don’t find a lot of these Spanish-style griddles,” she said. “Thus, there’s more continuity outside of the missions during the historic period.”

Unraveling a Mystery

As a native of North Carolina who did her undergraduate work at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Melton was familiar with the history of Native American tribes of the Piedmont area of the state during the colonial period (1670-1783). It was a brutal time when Native slavers, usually from Virginia or farther northwards, abducted untold numbers of women and children.

That history, though, was complicated by divergent narratives. Melton noted that the extant archaeological record suggested that daily life for Native Americans in the Piedmont was practically unchanged from the era before Europeans arrived. But written records told of a period of horrific slaving raids and widespread fear.

Melton, whose undergraduate honors thesis touched on indigenous foodways in the Piedmont, set out to reconcile those narratives. She conducted a quantitative analysis of botanical remains and architecture over time at the Wall and Jenrette villages in the Eno River Valley.

She found that, botanically, there was continuity during the transition to the colonial period, but with a twist: “People are using the same resources,” she said, “but they’re using them in different proportions. In the case of maize they are using them in different ways.”

The lack of maize processing debris in the colonial-period Jenrette village suggests they were conducting these activities elsewhere. The question was, Why? “I interpret this pattern to be indicative of a field-scattering strategy,” Melton said, “where these people are creating multiple, dispersed smaller fields, instead of one larger field within the settlement. And they’re spacing them at perhaps multiple distances from the settlement. It seems they’re doing that as a way, in combination with this increase in use of foraged food, of improving their chances of obtaining adequate subsistence.”

In short, having multiple fields is a way to minimize the risk and damage of the inevitable raiding parties looking for food and captives.

“That’s my argument in the article,” Melton explained. “You’ve got multilayered benefits here. Field scattering could allow for scattered harvesting times, reducing the gravity of crop loss from any one raid, and potentially create a situation where unoccupied outfields are being attacked.

“This foodways data bridges the gap between the archaeological and historical evidence,” Melton continued. “It really demonstrates that Native peoples of the Eno River Valley are feeling the effects of all the very grave and serious social problems going on at this time. And they’re not living in harmonious seclusion, so to speak. The take-home message of this study is that even when we are researching Native people that are not being impacted by European diseases and we don’t have clear evidence for engaged, long-term trading relationships with Europeans, we can still use food remains to see the extent to which these peoples’ everyday lives were affected by the devastating and pervasive impacts of colonialism.”