A Pound of Cure

For indigenous people around the world, high rates of illness and mortality are a way of life. Most have limited access to health care, certainly, but many choose not to not take advantage of it even when it becomes available.

Why that is the case has long been a topic of speculation among health care providers and development workers. Common beliefs are that indigenous people are simply unfamiliar with the value of medical treatment and preventative care, or they are deterred by distrust and discrimination.

A Rational Response

But a new study by anthropologists at UC Santa Barbara, Chapman University and the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse, France, shows that in the case of the Tsimane, an indigenous population in the Bolivian Amazon, the choice not to seek medical care may actually be a rational response to living in a harsh and unpredictable environment. What might really matter is whether people perceive that their actions can effectively impact their health.

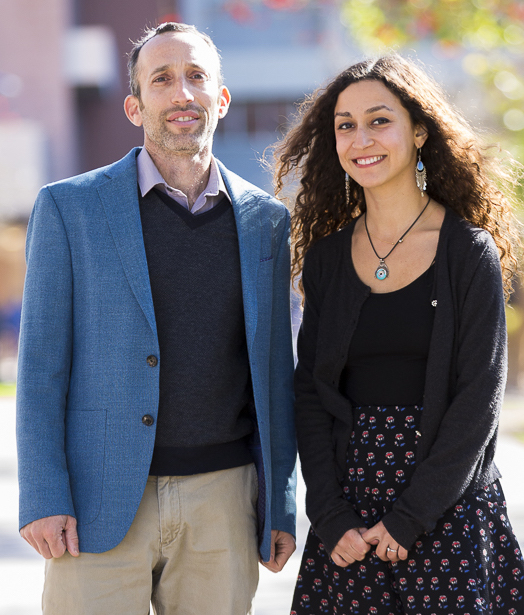

The researchers’ work, which appears in the journal Social Science & Medicine, is the latest from the Tsimane Health and Life History Project (THLHP). Co-founded and co-directed by Michael Gurven, a professor of anthropology at UCSB, and Hillard Kaplan of Chapman University, THLHP researchers have been following several thousand Tsimane over the past 16 years to better understand how features of their ecology, lifestyle and social behavior impact their health and wellbeing.

What Shapes People’s Health Care Decisions

“While collecting different types of health information, our biomedical team treats patients for many common ailments they have,” said Gurven, the senior author of the paper, who designed the study. “In most villages there’s a lot of sickness but there’s no health outpost and no physician or nurse.” In some rural areas — such as the Bolivian highlands — everyone would eagerly take advantage of free medical care if it were readily available, he went on. His team found, however, that even after gaining villagers’ trust, some ill people simply aren’t motivated to visit their free clinic.

“If some people are not inclined [to seek medical treatment] when we are there, imagine the situation when we’re not; so the question arises: what shapes people’s decisions to seek treatment, whether at the hospital, clinic or pharmacies in town — or in the surrounding forest to obtain local plants for traditional remedies,” Gurven continued. “We’re trying to understand more broadly why people might not always seek out care despite high need.”

The Health Locus of Control

The researchers used a construct — the health locus of control — as a window into an aspect of the Tsimane’s decision-making process that isn’t usually considered. It’s not just an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, the effectiveness of antibiotics or other related knowledge that affects decision making, they note, but an individual’s own belief about the extent to which his or her actions might matter.

“If you’re ‘internal,’ you believe you have a lot of control over your health, or self-efficacy,” explained Sarah Alami, an anthropology graduate student at UCSB and the paper’s lead author. “You might believe that treatment will heal you, or that things you do may affect whether or not you get sick in the first place.”

The researchers found that “externals” who believe their health is influenced more by chance or fate than their own ability to look after themselves are less likely to seek out a doctor or health clinic — regardless of whether they live close to town or farther away, and even if they have a relatively high level of education.

A Sensible Use of Resources

A similar logic has been shown to matter in the United States and other high-income countries. If you believe your actions matter, according to the researchers, you’ll attempt to seek treatment if you’re sick. You’ll get yourself to the doctor. You’ll take the medications prescribed. You’ll even practice preventable behaviors because you know that matters — all this because you believe you are responsible for your own health.

“But if you’re a Tsimane with limited resources, spending considerable effort and money to trek to the hospital to treat an intestinal parasite or a chronic respiratory infection might not make sense,” Alami said, “particularly given that when you come back to your community you may get reinfected, or suffer other traumas such as a snake bite or a stingray sting.”

In this tropical environmental context where infection runs rampant and trauma and natural disasters such as serious floods are commonplace, much morbidity and mortality seems beyond one’s control, Gurven noted. “It’s not crazy to think your actions might not matter much, relative to chance and haphazard misfortune,” he said. “In the face of such unpredictability, people may be inclined to value the present and to discount the future. In a more stable, predictable environment, an internal locus of control that involves careful planning and a more future-oriented mindset might be favored.”

Self-efficacy vs. Education as a Predictor

According to Gurven, one novel approach the researchers took was to separate the “external” aspect into multiple dimensions: chance or luck; spiritual sources such as forest spirits, God and sorcery; and powerful others such as leaders, shamans and physicians — those you believe can direct your fate, even if you cannot do so yourself.

It turns out those “external” dimensions do, indeed, matter. More broadly, however, the psychological construct of self-efficacy matters quite a bit. It, more than education, predicts a greater likelihood of seeking out health care for common ailments, even after taking other factors into account.

“Our results show that health care decisions may be quite rational,” Alami added. “Living far away from town means you’re less likely to seek modern care, but that doesn’t affect your decision to use traditional remedies. Accidents such as machete cuts and tree falls are serious enough to motivate the trip to seek modern treatment. Chronic intestinal parasites are more likely to be treated using local remedies, or go untreated. A bad respiratory infection isn’t going to kill you in three days like a snake bite will; it may kill you in five years.”

Without imminent danger, avoiding costly treatment for a chronic respiratory illness might seem like a reasonable course of action, especially if other dangers might kill you first. And when time and financial resources are tight, that rationale makes even more sense.

The medical team makes annual visits to more than 50 Tsimane villages, and for this study they sampled 690 adults. They asked each individual whether in the past month he or she has had a respiratory infection, a gastrointestinal infection or some incidence of trauma. A yes response to any of these elicited additional questions about illness duration and disability, and whether any type of medical treatment was sought. “In a third of the more serious cases, people do go and seek modern treatment,” Gurven said. “And in another third of cases people sought traditional, plant-based treatment.”

The Impact of Modernization

The researchers also wanted to look at the role of modernization in the relationship people have with healthcare. As people become more educated, aware and trusting of Bolivian institutions, they are more likely to take advantage of the modern health care.

“Do you become more internal and believe you have more control as you become more modernized?” Alami asked.

“We wanted to see whether modernization matters because of greater understanding and familiarity with Western medicines, assessed in our study by measures of formal schooling, Spanish language fluency and town proximity,” Gurven said. “Or does modernization matter because it changes your perception of self-efficacy?”

The team found that both education and location — where you live — affect psychological outlook. But locus of control and town proximity had separate, independent effects on whether someone sought treatment, and level of schooling did not predict treatment behavior. In other words, locus of control does not explain the relationship they found between modernization and seeking treatment.

Findings Applicable Around the World

According to Gurven, the study has implications for contemplating healthcare decisions all over the world, including the United States. “For example, why is it often so hard for people to adopt the lifestyle behaviors they know will lower heart disease risk? We largely have the knowledge of what’s good or bad for us, but that’s not enough,” he said. “What might matter is how people balance costs and benefits in the present against those in the future. Whenever people feel like they can’t control what happens to them, they may ignore advice about disease prevention for heart disease and other chronic, non-communicable diseases that afflict us at late ages.”

Your decision to eat healthy, exercise, not smoke or engage in other risky behaviors are likely affected by over-valuing the present relative to the future — a trait that makes sense only if you feel you live in a harsh and unpredictable environment, Gurven continued. “And with that psychological mindset, no amount of education or public service announcements may convince you otherwise,” he said.

Other contributors to the paper include Kaplan and Jonathan Stieglitz of the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse, France.