Engineering Arteries

Stem cell biologists have tried unsuccessfully for years to produce cells that will give rise to functional arteries and offer physicians new options for combating cardiovascular disease, the world’s leading cause of death.

But new techniques developed by scientists from UC Santa Barbara, the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Morgridge Institute for Research have produced, for the first time, functional arterial cells at both the quality and scale to be relevant for disease modeling and clinical application.

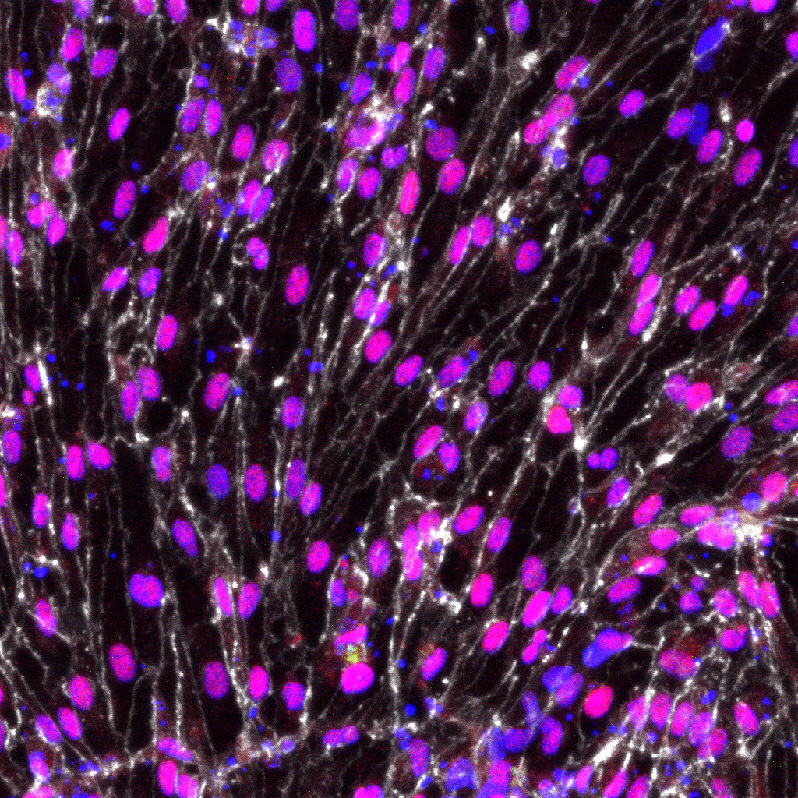

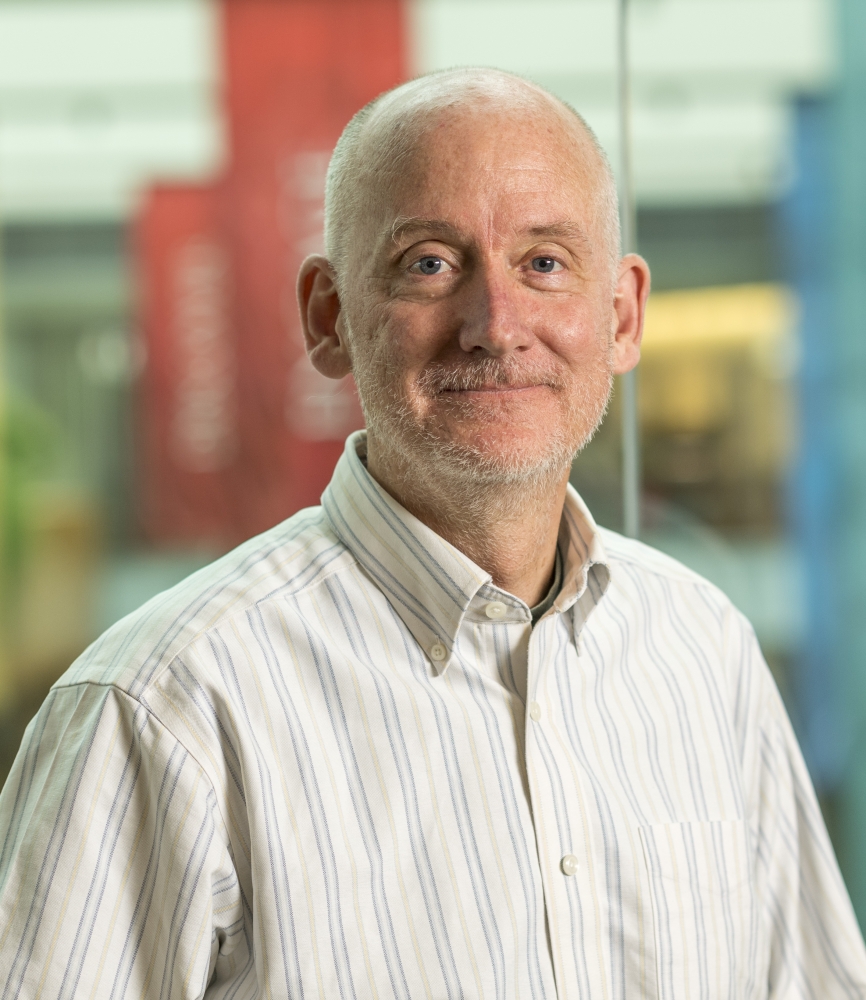

Reporting in the July 10 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers in the lab of stem cell pioneer James Thomson describe methods for generating and characterizing arterial endothelial cells — the cells that initiate artery development — that exhibit many of the specific functions required by the body.

Further, these cells contributed both to new artery formation and improved survival rate of mice used in a model for myocardial infarction. Mice treated with this cell line had an 83 percent survival rate, compared to 33 percent for controls.

“Our ultimate goal is to apply this improved cell derivation process to the formation of functional arteries that can be used in cardiovascular surgery,” said Thomson, a professor in UCSB’s Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, where he serves as co-director of the Center for Stem Cell Biology & Engineering. “This work provides valuable proof that we can eventually get a reliable source for functional arterial endothelial cells and make arteries that perform and behave like the real thing.”

“The cardiovascular diseases that kill people mostly affect the arteries, and no one has been able to make those kinds of cells efficiently before,” said Jue Zhang, a Morgridge assistant scientist and lead author. “The key finding here is a way to make arterial endothelial cells more functional and clinically useful.”

Cardiovascular disease accounts for one in every three deaths each year in the United States, according to the American Heart Association, and claims more lives each year than all forms of cancer combined. The Thomson lab has made arterial engineering one of its top research priorities.

The challenge is that generic endothelial cells are relatively easy to create, but they lack true arterial properties and thus have little clinical value, Zhang said.

The research team applied two pioneering technologies to the project. First, they used single-cell RNA sequencing to identify the signaling pathways critical for arterial endothelial cell differentiation. They found about 40 genes of optimal relevance. Second, they used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology that allowed them to create reporter cell lines to monitor arterial differentiation in real time.

“With this technology, you can test the function of these candidate genes and measure what percentage of cells are generating into our target arterial cells,” said Zhang.

The research group developed a protocol around five key growth factors that make the strongest contributions to arterial cell development. They also identified some very common growth factors used in stem cell science, such as insulin, that surprisingly inhibit arterial endothelial cell differentiation.

Thomson also is director of regenerative biology at Morgridge and a UW-Madison professor of cell and regenerative biology. His team, along with many UW-Madison collaborators, is in the first year of a seven-year project supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on the feasibility of developing artery banks suitable for use in human transplantation.

In many cases with vascular disease, patients lack suitable tissue from their own bodies for use in bypass surgeries. And growing arteries from an individual patient’s stem cells would be cost prohibitive and take too long to be clinically useful.

The challenge will be not only to produce the arteries, but find ways to insure they are compatible and not rejected by patients.

“Now that we have a method to create these cells, we hope to continue the effort using a more universal donor cell line,” said Zhang. The lab will focus on cells banked from a unique population of people who are genetically compatible donors for a majority of the population.