Art on the Set

One day in 1995 Constance Penley got a phone call that would change her life. On the other end was “this crazy artist from Texas” named Mel Chin, and he had a proposal for her. “I did not know him,” Penley recalled, “but he started explaining the project to me, and in 30 seconds I said, ‘I get it. I’m in’.”

The project, said Penley, a professor of film and media studies at UC Santa Barbara, was an ambitious collaboration to place provocative pieces of art on the set of “Melrose Place,” a primetime, 1990s soap opera on Fox populated by beautiful, libidinous and treacherous people. Nothing of the sort had been done before on television.

Known as the GALA Committee — it was formed at the University of Georgia (UGA) and the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles — it produced roughly 200 pieces of art in three seasons of shows. With dozens of collaborators, the committee designed and created works — with the blessing and assistance of the show’s producer — in a wide range of media and historical art forms that were used as props that defied censorship and tweaked social and political norms.

“We saw ourselves as a virus infecting ‘Melrose Place,’ ” said Penley, who recently gave a lecture/performance on the GALA Committee project in UCSB’s Pollock Theater. “But a good virus causing benign mutations.”

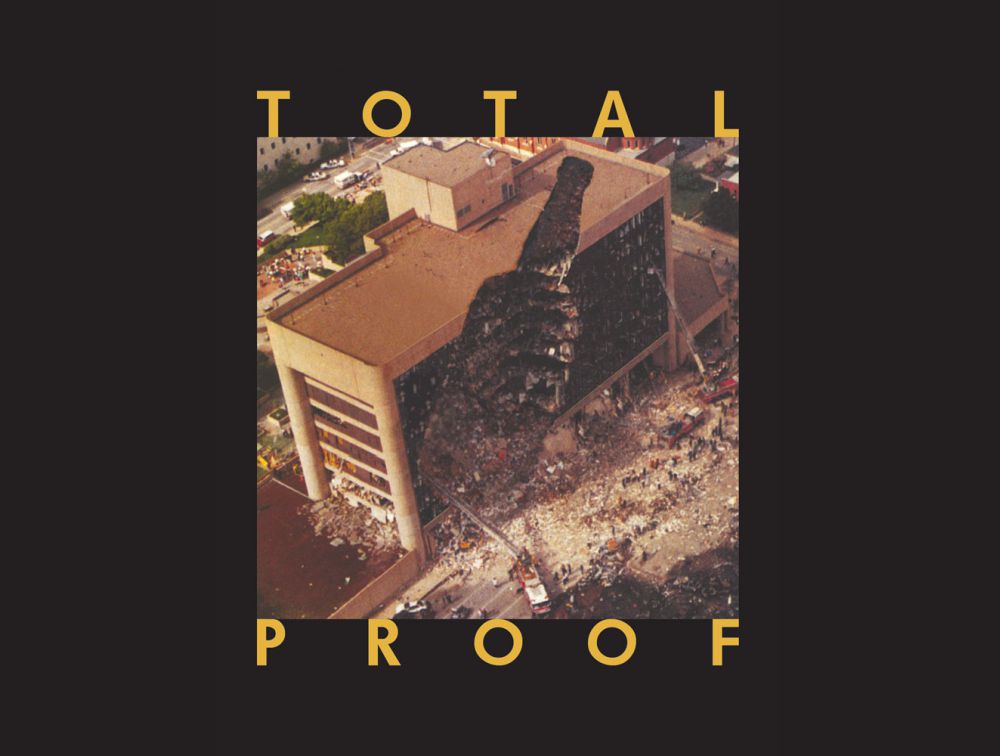

For a scene with a couple in bed, they created sheets printed with unrolled condoms, even now a no-no on network television. In another, a pregnant woman is wrapped in a quilt embroidered with the chemical compound for the abortion pill RU-486. A poster in another episode mimicked Absolut Vodka ads, showing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, which was destroyed in 1995 in a bombing that killed 168 people, with a crater in the shape of a bottle.

The project became, and remains, the biggest covert art project in television history. It spawned four exhibitions — at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the Kwangju Biennale in 1997, at Grand Arts in Kansas City in 1998, and at Red Bull Studios New York, which just ended. Penley said she hopes a smaller version of the New York show will come to UCSB in partnership with the school’s Art, Architecture & Design Museum and the Carsey-Wolf Center.

Penley participated in a discussion panel at the “TOTAL PROOF” exhibition in New York with Chin and other GALA Committee members; “Melrose Place” executive producer Frank South; cast member Rob Estes, who played Kyle McBride; and the original curators of the MOCA show, Julie Lazar and Tom Finkerperl, who is now commissioner of the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs.

“All of us on the panel and in the audience were haunted by how much the issues we raised in the project 20 years ago are so (newly) relevant today, post-election,” Penley said. “These issues ranged from domestic and international terrorism; global environmental and public health; the corruption of the pharmaceutical industry; sexual politics and sex work; reproductive choice; immigration; the history of race and racism in America; the lack of democratic control over media content and conduits; government and corporate censorship; the dangers of mainstream corporate advertising; gays in the military, marriage equality and other LGBT issues; and, of course, many issues in the art world such as women’s unequal representation and the challenges and opportunities of artmaking under authoritarian regimes and corporate capitalism.”

Penley, who has done presentations on the GALA Committee around the world, said that while the project addressed all those issues, it was more than a subversive act of art. “We still have to resist the idea that we were ‘guerilla artists’ transgressing television,” she explained. “Our focus instead was on collaboration. We were working together with the TV producers and cast and crew and writers to cross the bandwidths of art and television as much as possible. We wanted to use art to make television better, and television to make art better.”

Penley came to the GALA Committee as its media scholar. She was a pioneer in the study of underground female media fan culture, in which “slash fans” pick two characters from a TV show and write homoerotic pornographic romances about them. Imagine Capt. Kirk and Mr. Spock from “Star Trek.” Today it’s known as “shipping” or “mashing up.” With Chin’s invitation, she said, “I saw immediately what an opportunity this would be to get inside a show and rewrite it from the inside out. And then working with the producers of the show, too, to make this new text. You could say that we created the world’s largest art video, now being beamed down around the planet in endless syndication on Rupert Murdoch’s satellite system.”

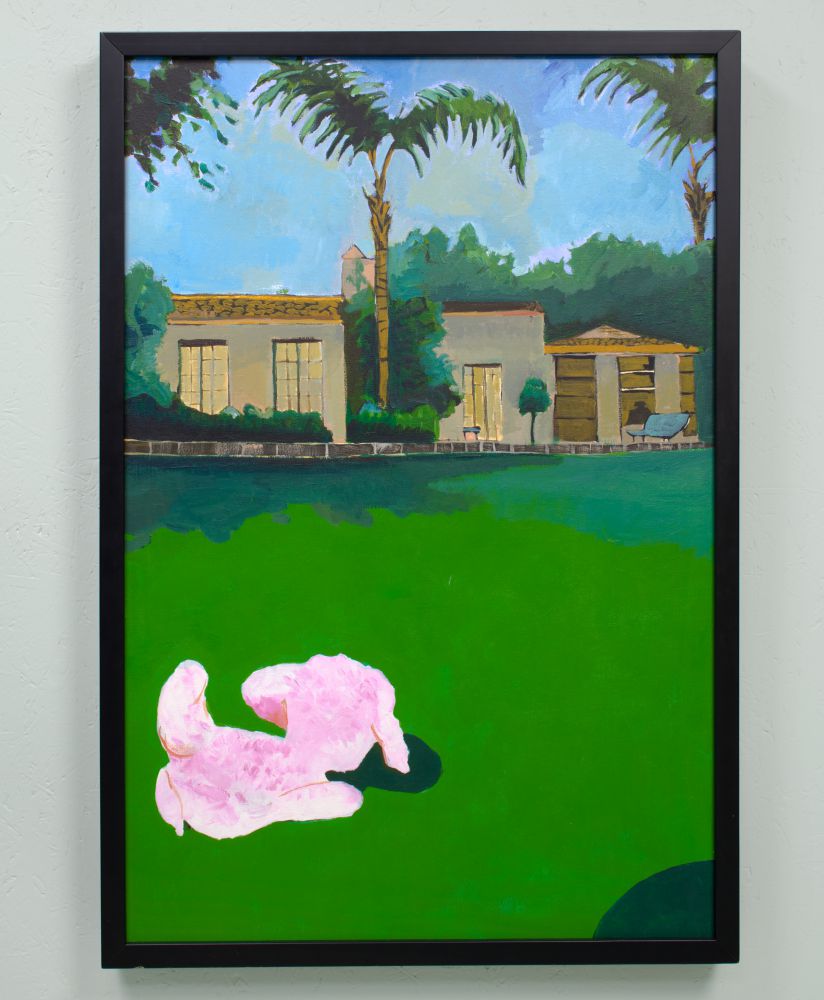

One of the project’s striking collaborations with the show involved the introduction of a new character — a young artist named Samantha Reilly — just for the GALA Committee. To hash out the character, Penley, nine women artists and the show’s head writer, Carol Mendelson, met at Grand Arts in Kansas City, Mo. The only requirement for the character, played by Brooke Langton, was that she be a painter whose works were reminiscent of David Hockney’s vibrantly colored California Dreaming paintings.

“We might have wanted something more avant-garde, but in the spirit of improv, we went with it,” Penley noted. But there was, of course, a twist. “Sam paints all the Southern California places where horrific murders or violence are going to occur, or have occurred.” The first was the bungalow where Marilyn Monroe died, taken from a police photo on the day of her death. Others included Chateau Marmont, where John Belushi overdosed; the Ambassador Hotel, where Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated; and the apartment complex from which the Rodney King beating was filmed. “The producers loved these paintings,” she said.

In the spirit of collaboration, the one rule Chin imposed for the works was that each had to be worked on by at least three people, and nothing was ever signed. “That’s something that drove curators, critics and journalists crazy,” Penley said. “Because they would say, ‘Who made that?’ And we would say, ‘We all made it.’ And to this day it irritates Mel Chin to no end when it’s written about as Mel Chin’s project.”

Twenty years on, the GALA Committee’s work on “Melrose Place” has lost none of its power. Soap operas and telenovelas, Penley notes, are among the most socially progressive art forms. The issues on “Melrose Place” — abortion, gay rights, war, AIDS, feminism and more — are still relevant today. The show and the GALA Committee were simply ahead of their time.

“People ask us all the time if the GALA Committee has plans for other television shows,” Penley said. “We reply, ‘Like we would tell you; you’ll just have to wait and see.’ ”