Dividing the Spoils of Cooperation

Many traits make human beings unique, not the least of which is our ability to cooperate with one another. But exactly how we choose to do that — particularly with nonfamily members — can be complicated.

For men, that choice relies partially on perceptions of productivity and material benefit, just as it would have in an ancestral hunter-gatherer society. So finds a new study by UC Santa Barbara psychologists, which appears in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior.

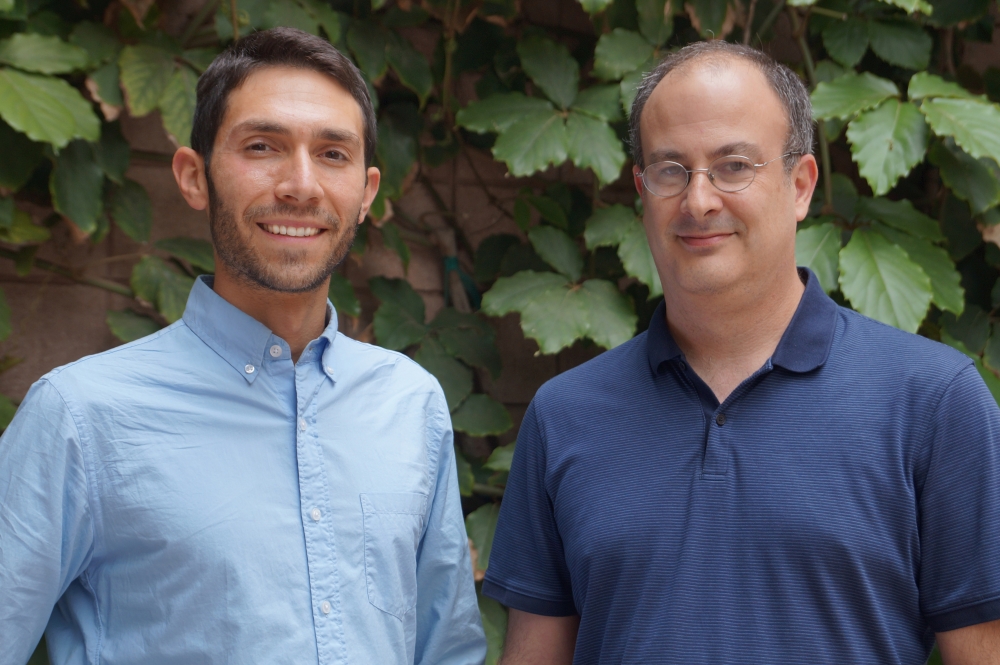

“It’s interesting that those mechanisms are designed for the environment of our ancestors, not our current context, yet they affect how people behave today,” said lead author Adar Eisenbruch, a Ph.D. candidate in evolutionary psychology.

The researchers used an experimental economics game to determine the traits to which players are sensitive beyond the structure of the game itself. In this one-shot bargaining construct, the proposer offers a specific split of a fixed sum of money and the responder either unconditionally accepts the offer or rejects it, in which case both players receive nothing.

“Our initial prediction was that men with stronger and more threatening-looking faces — as indexed by width — might be treated better, but that’s not what tended to happen,” explained senior author James Roney, a professor in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences. “It turned out that men with wider faces actually were treated worse in the game while men who were physically stronger were treated better. Our results showed that the choice of cooperative partners isn’t entirely determined by prosocial traits like generosity and trustworthiness, but also by cues that indicate whether someone would have been a productive partner in a hunter-gatherer society.”

Subjects played the game with a set of faces that were rated by a different group for characteristics such as attractiveness, dangerousness, social status and productivity, the last of which represents perceived hunting ability in an ancestral environment. When the investigators controlled for how productive a man looked, dangerousness became a negative predictor of how well he was treated.

“That makes a lot of sense,” Eisenbruch said. “If you’re going to have a long-term cooperative relationship, you don’t want a partner who looks like he would use his strength to exploit you. You want someone who looks like he has enough strength to be really productive.”

Roney noted an important correlation between the degree to which individuals claimed they would want to be friends with people based on their faces, and how well other men treated them in the game. “What we’re suggesting is that these psychological mechanisms get engaged by the structure of the game and then people act as though it’s a social interaction, as if this were an opening bid to be friends or have a cooperative relationship,” he explained.

In fact, participants actually decreased their earnings in the game by adhering to this approach. “It seems like the mental mechanisms that people use when they play this game aren’t designed to maximize how much money they make right now,” Eisenbruch said. “Instead, they seem to be designed to secure the best available long-term cooperative relationship based on what partners are available in the environment. Players are willing to sacrifice immediate game earnings in order to do that.”

The same study was repeated with women who played the game with female partners. The psychologists expected to see no effect of strength in women and, in fact, that was true.

“We also found — as you might expect — a weaker effect of productivity in women than in men,” Eisenbruch said. “In women, it seems prosociality trumps productivity, which suggests that men have evolved to engage in specific types of cooperation, like large game hunting and coalitional warfare, where getting a partner who’s good at those things really, really matters.”

Women cared more about reciprocity. They made higher offers to women who were rated more attractive, healthier and more prosocial, and also demanded more from attractive partners. On the other hand, men offered more to attractive people but demanded less of them.

“Women in the proposer role would offer more money to attractive women, but in the responder role demanded more from attractive partners,” Roney explained. “It wasn’t that they were always treated better.” One possible explanation for this, he suggested, is that for women the initial offer of a cooperative relationship with a more attractive partner was accompanied by demands that said: “I also want you to treat me well. Otherwise, I’m not going to accept this relationship.”

These experiments demonstrate that personal characteristics matter in cooperative partner choice, albeit differently across gender lines. “We’ve not only reframed how subjects interpret the game, but we’ve also shown that people have evolved mechanisms for choosing long-term cooperative partners,” Eisenbruch said.