'A Brutal Life That Lasted Years and Years'

Last August, German Chancellor Angela Merkel became the first German head of state to visit the former concentration camp at Dachau. While there, she expressed “deep sorrow and shame” at the crimes perpetrated by the Nazi regime.

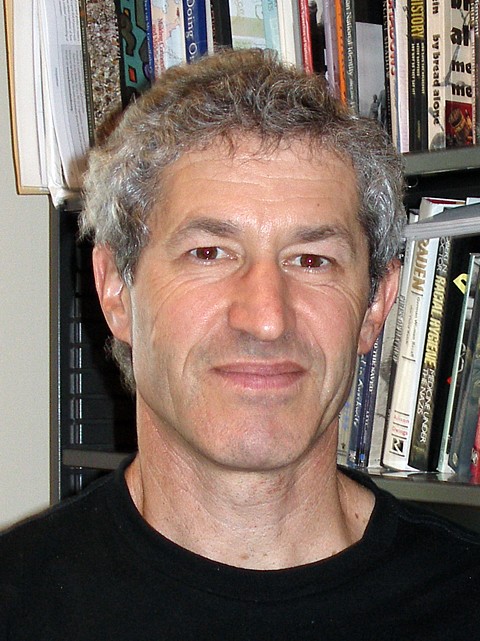

Harold Marcuse, an associate professor of modern German history at UC Santa Barbara, noted at the time that previous chancellors had purposely avoided the site. Until recently, he said, it “has been considered toxic for most German politicians, especially on the right.” Marcuse is the author of “Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001.”

“The focus of my historical work is on how remembrance changes over time,” Marcuse said. “It looks at how something happens, how it gets interpreted and becomes an event to be remembered and how its own infrastructure is developed around it.”

Dachau is a prime example.

Situated northwest of Munich in southern Germany, Dachau opened in 1933. It was the first official concentration camp. Under the direction of Heinrich Himmler it expanded from a political prison to one that included forced labor and the infrastructure for mass murder. Although the gas chambers were never put into full operation, starvation and epidemics in the last phase of the war produced mass death in the camp on their own. This affected primarily Jews from across Europe but also German and Austrian prisoners and foreign nationals from countries Nazi Germany occupied or invaded.

The camp was also used as a training center for both the camp guards and the military branch of the German Schutzstaffel (SS), which Himmler commanded.

By the time Dachau was liberated on April 29, 1945, well over 200,000 prisoners had passed through its gates and more than 42,000 died there.

“In my research on Dachau I look at what the camp actually was during the 12 years of its existence and what people thought of it during that time. Then, once it was liberated, which of those images continued, which new ones emerged and how they were reflected by the uses of the site,” Marcuse said. “It was a concentration camp with several functions, then a refugee settlement and finally became a memorial site. And it took 20 years for that to happen.”

Dachau became an official memorial site in 1965.

Until recently, most Germans didn’t want to remember the persecution and genocide practiced during the Nazi period. West German politicians feared a backlash if they associated with a site like Dachau.

“Beginning in the 1980s researchers began to nuance the prevailing ‘death camp’ image of the site,” Marcuse said. “At the same time older generations were losing public influence, while curious and more open generations were interested in learning more about Nazism. That provided the opening for politicians to visit Dachau.”

When President Reagan went to Germany in 1985 to commemorate the end of the war, the Germans wanted him to visit only the Bitburg military cemetery. Pressure from the U.S. forced the addition of a Nazi camp to his itinerary. First Dachau was chosen, but then dropped because it was considered “too grisly.” Bergen-Belsen was chosen instead. That camp had been leveled after the war and never reconstructed. Since Reagan’s visit, there have been excavations and a new museum there, but it is still mainly forest and field.

How does Dachau as a place — or any of the former concentration camps, for that matter — contribute to our collective memory or understanding of the Holocaust and of atrocities that are seemingly beyond our comprehension? By giving visitors a means of envisaging the camp and all its components, according to Marcuse.

“I’m much more open to reconstruction,” he said. “Not what Germans pooh-pooh as the ‘Hollywoodization’ of a historical site, but some kind of abstracting reconstruction. A normal visitor might spend a few hours there and get a gestalt impression. My argument is you want that gestalt impression to represent what was actually there. What people tend to extract and remember now is that there’s a big building, a gate and a crematorium, with a lot of gray in between.”

But Dachau was not only an extermination factory. Tens of thousands of inmates worked in local Dachau factories, producing for the war effort — 150,000 inmates, most of them non-Jews, survived. “The non-Jews were in the camp for years. What was their experience?” asked Marcuse. “Should visitors to the memorial learn about them?”

“The farther we get from these events and the less we — the general public — know about them, the harder it is to get that intuitive gestalt grasp of what happened,” Marcuse said. “There was a brutal life that lasted years and years. These were not just extermination factories where living people came in and corpses left as smoke.”

The passing of time — and of generations — requires us to update how we remember, and whom we put in charge of the memories, according to Marcuse. “Who determines what is and is not represented at the site?” he continued. “There’s a difference between remembering while there are still survivors. And once there aren’t people who had a stake in the events themselves, is it their children we will listen to about how to change the site? Is it they who will decide how we will commemorate?

“I think commemoration changes when there are no survivors, when those voices are gone,” he noted. “We don’t yet know whether the descendants of survivors want to have a say, or even whether they should have the primary say.”

How the community of survivors chooses to commemorate is yet another issue. At Dachau, men imprisoned for being gay were required to wear a badge featuring a pink downward-pointing triangle (Jews wore two triangles superimposed to create a yellow star.) The pink triangle has since been reclaimed as an international symbol of gay pride and the gay rights movement.

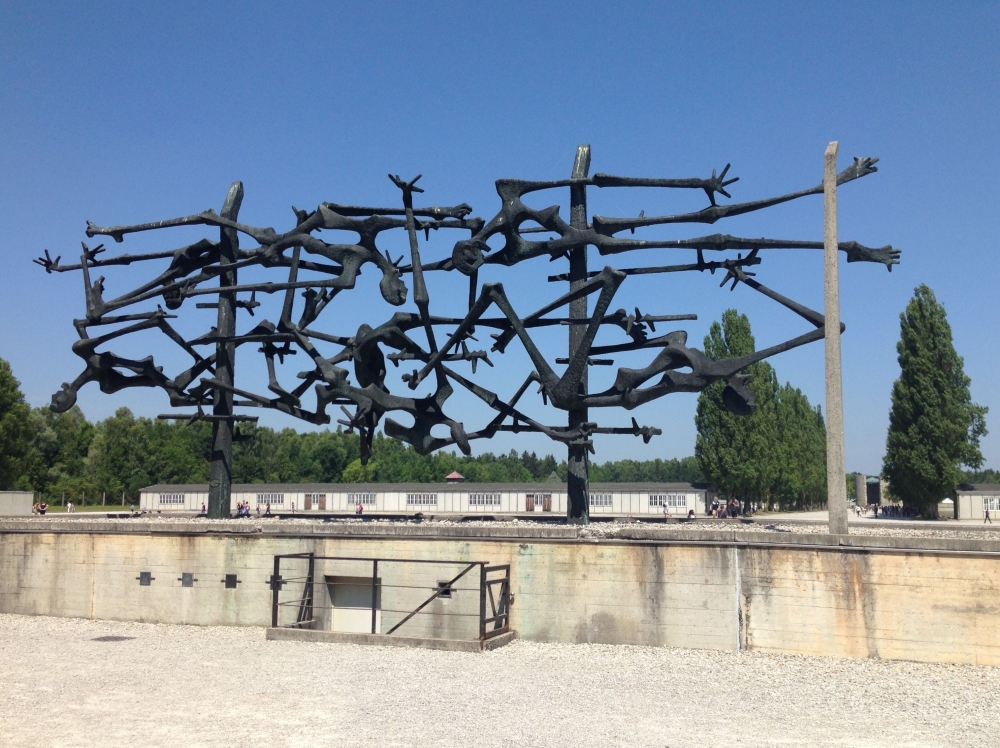

A memorial sculpture commissioned in the 1960s features colored triangles that represent the various categories of prisoners. Conspicuously absent, however, was the pink one. “At that time, many still saw homosexuality as a crime,” Marcuse said. “Pink was banned by the survivors who commissioned the memorial. When gay activists wanted to put up a pink granite triangle memorial in that space in the 1970s, they were refused. It had to be placed in the Protestant memorial church at the far end of the former camp.”

Twenty years later, that granite panel was moved to a special memorial room in the museum. “The community that is commemorating needs to have some say,” Marcuse continued, “but to what extent should one respect survivors’ rights if survivors are shutting out some of their own? It’s a complicated question.

“Memorial sites ultimately reflect the goals of commemoration of the power-holders of a given time and place,” Marcuse said. “They may or may not reflect what actually happened in the past, but rather the images of history that later generations hold and want to propagate. As those images and values evolve, so, too, do memorial sites. It’s a dialectical process: a changed memorial site can then in turn help to change and solidify new understandings of the past.”