An interdisciplinary team of researchers at UC Santa Barbara has produced a groundbreaking study of how nanoparticles are able to biomagnify in a simple microbial food chain.

"This was a simple scientific curiosity," said Patricia Holden, professor in the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and the corresponding author of the study, published in an early online edition of the journal Nature Nanotechnology. "But it is also of great importance to this new field of looking at the interface of nanotechnology and the environment."

Holden's co-authors from UC Santa Barbara include Eduardo Orias, research professor of genomics with the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology; Galen Stucky, professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and materials; and graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, and staff researchers Rebecca Werlin, Randy Mielke, John Priester, and Peter Stoimenov. Other co-authors are Stephan Krämer, from the California Nanosystems Institute, and Gary Cherr and Susan Jackson, from the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory.

The research was partially funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) STAR Program, and by the UC Center for the Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (UC CEIN), a $24 million collaboration based at UCLA, with researchers from UCSB, UC Davis, UC Riverside, Columbia University, and other national and international partners. UC CEIN is funded by the National Science Foundation and the EPA.

According to Holden, a prior collaboration with Stucky, Stoimenov, Priester, and Mielke provided the foundation for this research. In that earlier study, the researchers observed that nanoparticles formed from cadmium selenide were entering certain bacteria (called Pseudomonas) and accumulating in them. "We already knew that the bacteria were internalizing these nanoparticles from our previous study," Holden said. "And we also knew that Ed (Orias) and Rebecca (Werlin) were working with a protozoan called Tetrahymena and nanoparticles. So we approached them and asked if they would be interested in a collaboration to evaluate how the protozoan predator is affected by the accumulated nanoparticles inside a bacterial prey." Orias and Werlin credit their interest in nanoparticle toxicity to earlier funding from and participation in the University of California Toxic Substance Research & Training Program.

The scientists repeated the growth of the bacteria with quantum dots in the new study and and coupled it to a trophic transfer study –– the study of the transfer of a compound from a lower to a higher level in a food chain by predation. "We looked at the difference to the predator as it was growing at the expense of different prey types –– ‘control' prey without any metals, prey that had been grown with a dissolved cadmium salt, and prey that had been grown with cadmium selenide quantum dots," Holden said.

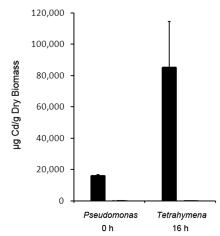

What they found was that the concentration of cadmium increased in the transfer from bacteria to protozoa and, in the process of increasing concentration, the nanoparticles were substantially intact, with very little degradation. "We were able to measure the ratio of the cadmium to the selenium in particles that were inside the protozoa and see that it was substantially the same as in the original nanoparticles that had been used to feed the bacteria," Orias said.

The fact that the ratio of cadmium and selenide was preserved throughout the course of the study indicates that the nanoparticles were themselves biomagnified. "Biomagnification –– the increase in concentration of cadmium as the tracer for nanoparticles from prey into predator –– this is the first time this has been reported for nanomaterials in an aquatic environment, and furthermore involving microscopic life forms, which comprise the base of all food webs," Holden said.

An implication is that nanoparticles inside the protozoa could then be available to the next level of predators in the food chain, which could lead to broader ecological effects. "These protozoa are greatly enriched in nanoparticles because of feeding on quantum dot-laced bacteria," Hold said. "Because there were toxic effects on the protozoa in this study, there is a concern that there could also be toxic effects higher in the food chain, especially in aquatic environments."

One of the missions of UC CEIN is to try to understand the effects of nanomaterials in the environment, and how scientists can prevent any possible negative effects that might pose a threat to any form of life. "In this context, one might argue that if you could ‘design out' whatever property of the quantum dots causes them to enter bacteria, then we could avoid this potential consequence," Holden said. "That would be a positive way of viewing a study like this. Now scientists can look back and say, ‘How do we prevent this from happening?' "

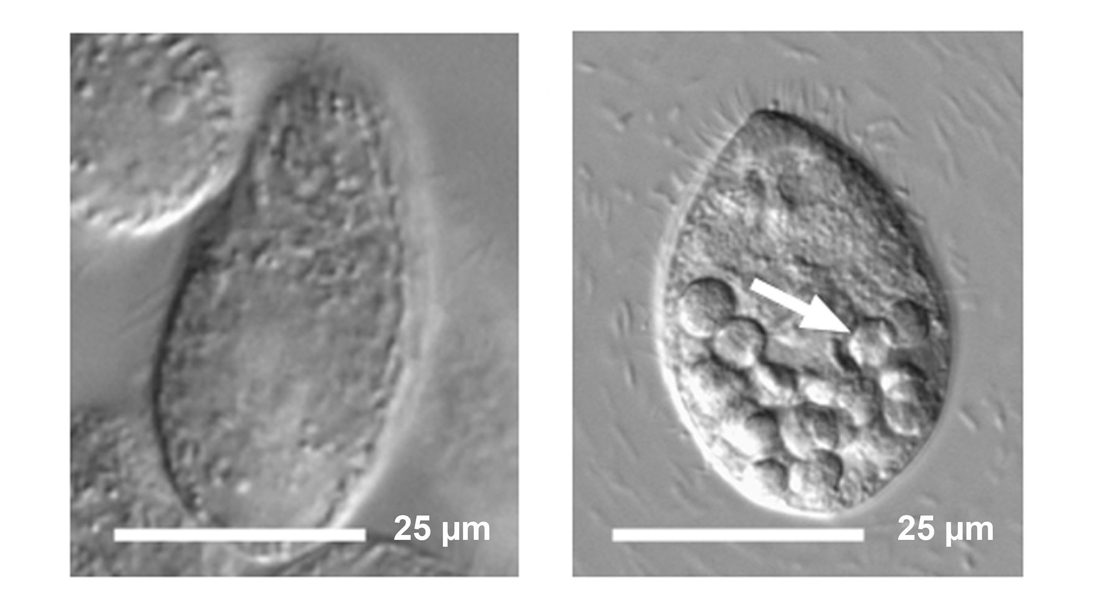

† Top photo: The quantum dot-tainted bacteria stop digestion in the protozoan, and food vacuoles with undigested material accumulate, seen in the right image.

This is in contrast to the normal condition of protozoa eating untreated bacteria, seen in the left image.

†† Bottom photo: The concentration of quantum dots (black bars), as measured by cadmium, increased from bacterial prey into the protozoan predator — an outcome called biomagnification.

Related Links