Examining Options

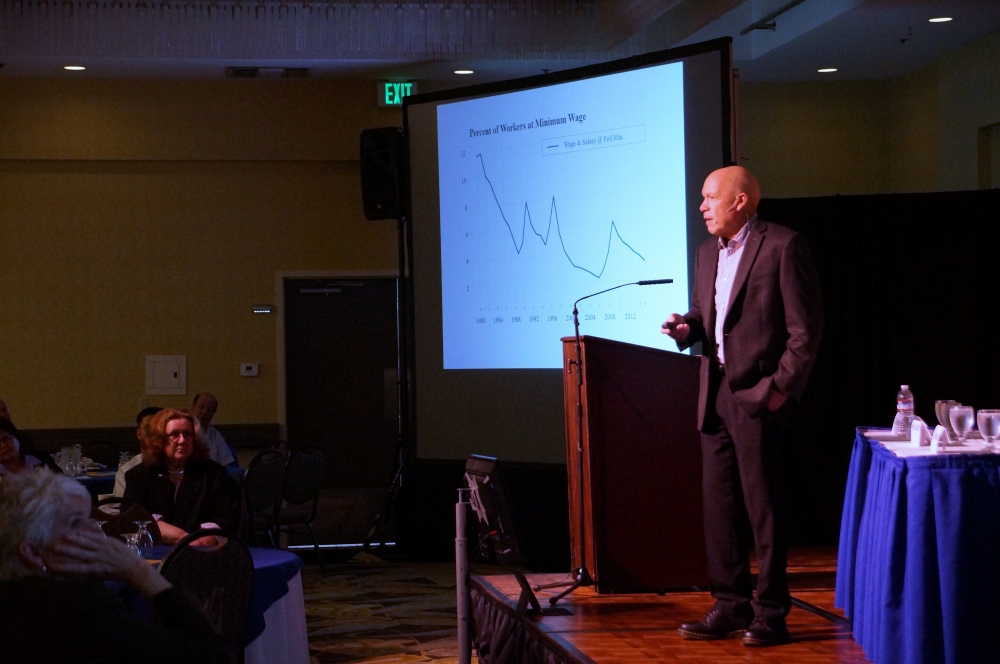

Making a living and doing business in Santa Barbara’s North County were among topics of discussion as UC Santa Barbara’s Economic Forecast Project (EFP) headed to Santa Maria for the second of two annual symposia on the state of the economy. The event held Friday, May 6, at the Radisson Hotel in Santa Maria, featured several talks on different aspects of North County business, in addition to the staple overviews on the local and regional economy presented by EFP Executive Director Peter Rupert, chair of UCSB’s economics department.

The economy in Santa Barbara County is trending upward, albeit sluggishly and unevenly. In the mostly rural and agriculture-based northern region, recovery from the Great Recession — indicated by housing values, employment and wages — is particularly slow relative to the more southern cities. While agricultural operations employ the most number of people in the county, wages are also on the low end, which tends to weaken people’s abilities to save, spend more money in their local stores and invest in their communities.

Allan Hancock College President Kevin Walthers knows higher education can help low-wage workers by providing training and opportunities for local students to branch out and develop skills, but for him the challenge is a geographic and financial one: Northern Santa Barbara County, he said, is an “education desert.”

“Education is how we all get out of an economic downturn,” Walthers said. “But right now, the State of California is not investing in higher education.” Student enrollments at public institutions are up, but the state budget has not grown with it, he explained. Compounding the problem in the North County, according to Walthers is that access to four-year institutions is limited, forcing students to drive, or live far away if they want to get their university degrees. Among possible solutions, he suggested, were satellite campuses of four-year institutions, and perhaps even the conversion of Allan Hancock into a baccalaureate-offering institution.

Beefing up North County’s education offerings could also spur high-tech industry in the area, added Henry Dubroff, editor-in-chief of the Pacific Coast Business Times. “If the Santa Maria Valley is going to emerge out of agriculture into this post-manufacturing era and attract tech companies, some sort of four-year institution is going to be important,” he said. Taking a cue from emerging hybrid semiconductor and software design and production operations in San Luis Obispo, South Santa Barbara County and Ventura County, he suggested that those industries could find footing in the North County if the conditions were right: education and an “x-factor” culture that could attract the high-tech brains and deep pockets of the tech industry.

In the shorter term, however, there are plans afoot to augment the local income as the region regains its economic footing. According to Santa Maria City Manager Rick Haydon, the city is rolling out programs to attract and retain small businesses and the jobs they bring. Additionally, the city is engaging in several large development projects to bring more commerce and homes to the area, as well as jobs and sales and property taxes.

“We wouldn’t be here today if there wasn’t development,” Haydon told the room.

Meanwhile, the recent $15 minimum wage bill that was signed by Gov. Jerry Brown was heavy on the minds of the summit speakers. Although the bill does not go into full effect until 2022, the outlook seemed bleak — at least at first glance — for the business-minded in North County.

“The legislators probably had the right idea,” commented Haydon, but at the state level didn’t realize the unintended local consequences of the bill’s implementation.

“It’s foolish to try to apply one standard to the whole state,” said Dubroff, adding concern about effects on overtime, salaried vs. hourly employees and the push toward automation to reduce the number of workers, particularly in the agricultural and service industries.

The new wage structure could have an impact in terms of housing costs, added Sacramento Bee journalist Dan Walters, who focused on what he saw as the looming housing crisis in California. “When those minimum wages kick in, landlords will — in their own interest —take advantage of that,” he said. New wages would get sucked into rents, he said, unless steps were taken to manage the state’s current housing shortage.